Dressing an Empire: The Woven World of Aztec Clothing

This exploration of Aztec clothing will take you on a journey through the materials they used, the societal rules that governed attire, the specialized garments of power, the economic might of textiles, and the lasting legacy of these traditions after the Spanish conquest. Navigate through the sections below to uncover the intricate details of this woven world.

Understanding Aztec Clothing: More Than Just Fabric

For the Mexica, the ancient people of Mesoamerica, clothing wasn't just about staying warm. It was a powerful visual language, a kind of "social text" that spoke volumes.1 Each garment, from the simplest cloak fiber to the style of sandals or a lip plug, clearly announced a person's status, job, gender, and even where they came from.

To delve into Mexica clothing is to uncover the very blueprint of the Aztec empire.

We believe the Mexica clothing system mirrored the empire itself: intricate, built on skilled production, ruled by strict laws, and rich with symbolism. To piece together this "woven world," we'll look at three main types of evidence.

First, and most vital, are the 16th-century historical accounts, or codices.3 Think of the detailed General History of the Things of New Spain (often called the Florentine Codex), the Codex Mendoza, and the Matrícula de Tributos.

These incredible records were put together shortly after the Spanish conquest by figures like Bernardino de Sahagún, who worked with Indigenous scribes and elders.6 They offer a unique, though somewhat filtered, window into Mexica life, society, and the things they made.

Next, we turn to archaeology. Central Mexico's humid climate means few ancient textiles have survived.9

However, the rare pieces found in sacred sites like Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco are incredibly important. These fragments give us real, touchable proof of weaving methods, fibers, and decorations, helping us verify what the codices tell us.

Lastly, we draw on the groundbreaking research of modern scholars like Patricia Rieff Anawalt and Frances F. Berdan.2 They've meticulously studied these varied sources to create a clear picture of Mesoamerican clothing.

By bringing all these viewpoints together, we'll explore everything from raw materials and production techniques to how textiles shaped society and the economy. We'll also examine the special outfits of warriors and priests, and finally, look at how the Spanish conquest changed everything and what legacy remains.

The Building Blocks of Aztec Style: Materials and Craftsmanship

The whole Aztec clothing system started with its raw materials. What your clothes were made of wasn't up to you, it was a legally enforced sign of your social standing.

The methods for turning fibers into cloth were closely tied to gender roles and daily life. The vibrant dyes, on the other hand, came from extensive trade networks and highly skilled artisans.

Fibers of Status: Cotton for Nobles, Maguey for Commoners

Mexica textiles mainly came from two fibers: ixtle from the maguey cactus (a type of agave), and ichcatl, or cotton.12 This basic difference was central to their clothing, drawing a sharp, legally enforced line between common folk and the elite.

Commoners, or macehualli, wore clothes made from ixtle. This fiber, taken from maguey leaves, resulted in a coarse, sturdy fabric ideal for the everyday wear of farmers and workers.12

Getting the fibers out was hard work, often needing men's strength to pull them from specially prepared leaves before spinning.1 Despite its everyday status, talented weavers, especially among the Otomi, could create impressively fine cloth from ixtle.1 Beyond clothes, ixtle was also used for practical items like bags and ropes.15

In stark contrast, cotton, or ichcatl, was a different story, it was strictly for the nobility, the pipiltin. Its softness and quality made it a luxury material, kept for the elite by strict laws.3

If a commoner was caught wearing cotton, the punishment could be death, showing just how important this rule was.18 Cotton was so prized it was more than just clothing, it served as currency and a key tribute item demanded by Tenochtitlan from conquered regions.1 They used both standard white cotton and a naturally brown "coyote-colored" type called coyoichcatl.1

This strict separation of maguey and cotton was more than just a status symbol, it was a cornerstone of the empire's economy and politics. By limiting who could use cotton, the state made it a scarce, valuable item they controlled.

This control meant cotton textiles, especially specific cloaks called quachtli, could be used like money and as powerful political gifts. The emperor could reward loyalty or bravery with cotton, something most people couldn't legally get otherwise.

So, the clothing law wasn't just about manners, it was smart economic planning. It created and managed a valuable resource that was key to the empire's tribute and reward system.

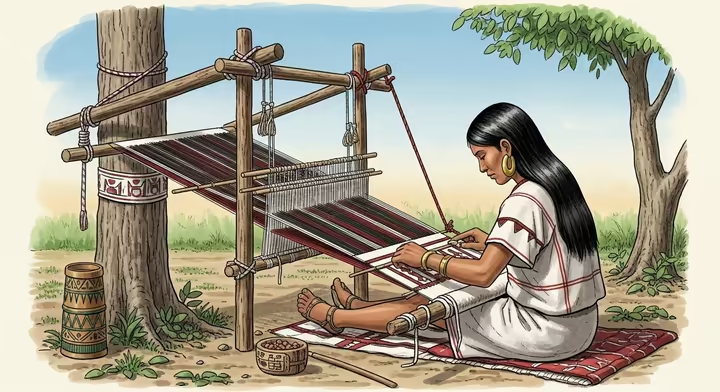

The Weaver's Touch: Mastery of the Backstrap Loom

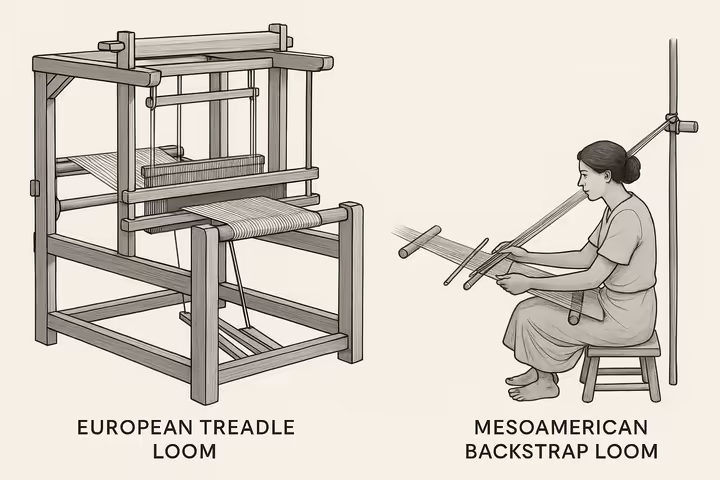

The main tool for making textiles was the backstrap loom, known as telar de cintura in Spanish.20 This clever and effective device, used across Mesoamerica for ages, was portable and incredibly versatile.22 It was key to producing the empire's most important economic product.

The loom is quite simple, without a fixed frame. It uses several rods to keep the warp (vertical) threads tight. The top part attaches to something stable like a post or tree, while the bottom part connects to a strap around the weaver's back.22

By leaning, the weaver uses her body to adjust the warp thread tension, creating a very personal connection with the fabric.24 A wooden batten (or "sword") presses the weft (horizontal) threads together, and a shuttle passes the weft thread through the warp.22

This design let weavers create very long pieces of cloth, though the width was limited by how far they could reach.25 Because of this, Mexica clothes were usually made from rectangular cloths that weren't sewn, with openings for the head and arms cleverly woven right in.12

Weaving was seen as the ultimate female skill. This role was set from birth when baby girls were given tiny spindles and weaving sticks, symbolizing their future roles in the home and economy.1

Girls learned the intricate arts of spinning and weaving from their mothers early on, usually becoming experts by age fourteen.1 This passing down of knowledge created a constant supply of skilled workers. These weavers, called tlamachchiuhqui (embroiderer) or tzauhqui (spinner), were vital to both family and empire economies.23

Because weaving happened at home with portable backstrap looms, women played a direct and important part in the economy.28 Yet, the empire cleverly used this home-based system on a massive scale for tribute.

The state didn't need big factories, it just tapped into the skilled female workforce in every conquered home to make its most crucial economic product. The huge amounts of textiles demanded as tribute, as seen in the codices, were made by countless women on their own looms.

This efficient system of using widespread, indirect labor didn't need much state oversight. It also helps explain why noblemen practiced polygamy: more wives meant a bigger home textile workshop, producing more wealth and meeting social and political demands.28

Colors of an Empire: The Art and Symbolism of Dyes

The Mexica lived in a world bursting with color, and their textiles were a main showcase for it. Dyers used a rich array of colors from plants, animals, and minerals, often obtained through the empire's vast trade and tribute systems.12

Color wasn't just for show, it was crucial for visually communicating status and symbolic meaning.19

Cochineal, called nocheztli in Nahuatl, was the most prized and valuable dye. It yielded vibrant, long-lasting reds, purples, and oranges.32

This precious color came from carminic acid, found in the crushed bodies of tiny female Dactylopius coccus insects that live on nopal cacti.32 The Mixtec people of Oaxaca perfected the difficult production process over centuries.35

Larvae were carefully raised and "planted" on cactus pads. After maturing for three to four months, they were hand-harvested, often with a tiny brush, then dried and ground into powder.32 This "cactus blood" was so valuable it became a major tribute item. After the conquest, the Spanish valued it almost as much as gold and silver.4

Other colors came from various sources too. Indigo plants gave rich blues,36 while certain trees provided yellows.30 The Mexica were also experts at dye chemistry.

By adding substances called mordants or changing the dye bath's acidity with things like lime juice or alkaline materials, they could get many shades from one pigment. For instance, cochineal could turn orange with lime juice or purple with salt.33

They also created complex patterns using advanced resist-dyeing methods. The blue-and-white tie-dye designs, similar to shibori, found on high-status capes in codices show their skill.37 These required careful binding of the fabric before dyeing to make the patterns.

Woven Status: Clothing, Social Rank, and Strict Dress Codes

In the strictly layered Mexica society, clothing was the quickest and clearest way to know someone's social standing. A detailed system of dress laws, or sumptuary laws, was enforced very seriously.

These laws made sure that a person's rank was literally written on their body. Whether it was a farmer's rough maguey cloak or a noble's shiny cotton and feather outfit, clothes and accessories acted as a visual guide. This system helped manage social interactions and support the power structure.

Everyday Attire: What Aztec Commoners Wore

The clothing of commoners, the macehualtin, was simple, practical, and made from legally required materials.12 For men, the basic item was the maxtlatl, a loincloth.39

This was a long piece of fabric passed between the legs and tied at the waist, with ends hanging in front. Farmers and workers might wear only this during hard labor.14

For more covering, they added a rectangular cloak called a tilmatli. Made from rough ixtle (maguey fiber), a commoner's tilmatli was usually plain.1 By law, it couldn't hang below the knees, clearly marking their lower status.

Commoner women typically wore two main items: the cueitl, a wraparound skirt, and the huīpīlli, a sleeveless tunic or blouse.39 The cueitl was a long rectangular cloth wrapped around the lower body and tied at the waist with a sash (cihua necuitlalpiloni).1

Skirt styles could differ by region, with some women pleating them in unique ways.12 The huīpīlli was a simple, straight tunic, often with some woven decoration near the neckline.41

Like men's commoner clothing, these were made from maguey, yucca, or palm fibers and were generally unadorned.16

Clothing also marked different stages of life. Children usually wore nothing until age three. Then, boys started wearing small capes, and girls simple blouses.

At four, girls added short skirts, which got longer as they grew. For boys, reaching adulthood at thirteen meant they could finally wear the maxtlatl.39

Dressing the Elite: Cotton, Colors, and Complexity

The wardrobe of the pipiltin, the hereditary nobles, was a world away. Their clothing was designed to shout status through exclusive rights to luxurious materials, brilliant colors, and intricate designs.

Their main privilege was wearing fine cotton garments, often dyed in stunning shades and elaborately decorated with embroidery and featherwork.3 The Florentine Codex even lists up to 54 different cloak styles for the elite, including one dramatically named centzontilmatli, or "four-hundred-color cloak."14

Even how a garment was worn was strictly defined. A nobleman tied his tilmatli over his right shoulder, setting him apart from a middle-class man who knotted his over the left.43

Only the huey tlatoani (emperor) could wear his long, heavily embroidered cloak tied at the front, a unique sartorial signature of supreme power.44 Prestigious garments had specific names, like the xiuhtilmatli (a prized blue cape) and the xiuhtlalpilli (a hip cloth decorated with turquoise, a stone reserved for the highest elite).39

Laws on Looks: Pre-Hispanic Sumptuary Rules and Enforcement

The differences in dress between classes weren't just about wealth or tradition, they were set in stone by strict sumptuary laws.2 These laws dictated the appearance of everyone in society.

Breaking these rules could lead to severe punishments, even death.19 The core rules were clear: commoners couldn't wear cotton cloth, sandals, or precious adornments like the shimmering feathers of tropical birds.13

The length, material, and decoration of the tilmatli were all legally prescribed according to one's rank.1 The pochteca, or long-distance merchants, offer a fascinating example of how effective these laws were.

Though they could become very wealthy, pochteca were commoners by birth. To avoid angering the nobility, they would sneak into the city at night after successful trade journeys, hiding their rich goods. In public, they purposefully wore simple maguey fiber capes, visually performing their lower status to stay in line.45

This system of sumptuary laws made society highly "readable." In a bustling city like Tenochtitlan, this visual system was vital for social order.

It allowed for instant recognition of an individual's status, guiding interactions and reinforcing the power structure without constant verbal or physical reminders. You knew immediately who had authority, who deserved respect, and who was a subordinate, simply by their clothes. These laws weren't just about keeping luxury from the poor, they ensured the smooth operation of a deeply layered society by making the hierarchy clear, unmistakable, and unavoidable.

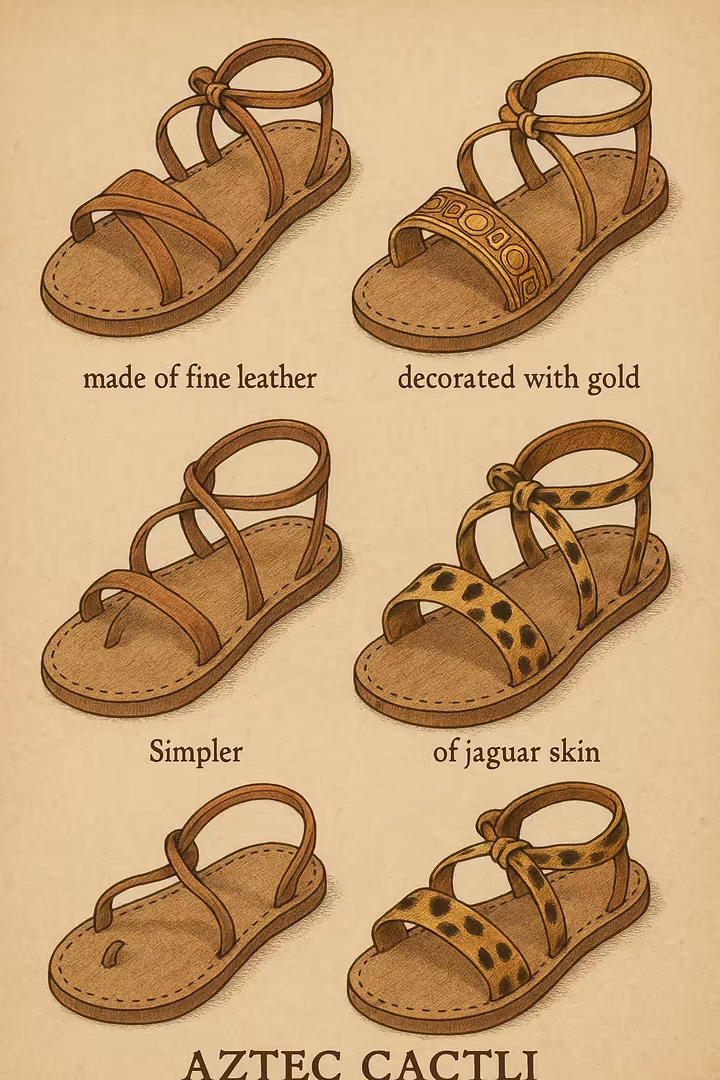

Adornments of Distinction: Sandals, Labrets, and Earspools

Beyond textiles, personal adornments like footwear and jewelry were powerful communicators of status, achievement, and even ethnic identity.

Footwear was a major status symbol. Sandals, or cactli, were a privilege mostly limited to noblemen, high-ranking warriors, and royalty.39 Commoners typically went barefoot.13

The importance of this distinction was highlighted by the rule that everyone, no matter their rank, had to be barefoot in sacred places like temples or before the emperor. This symbolized a leveling before divine and supreme political power.40

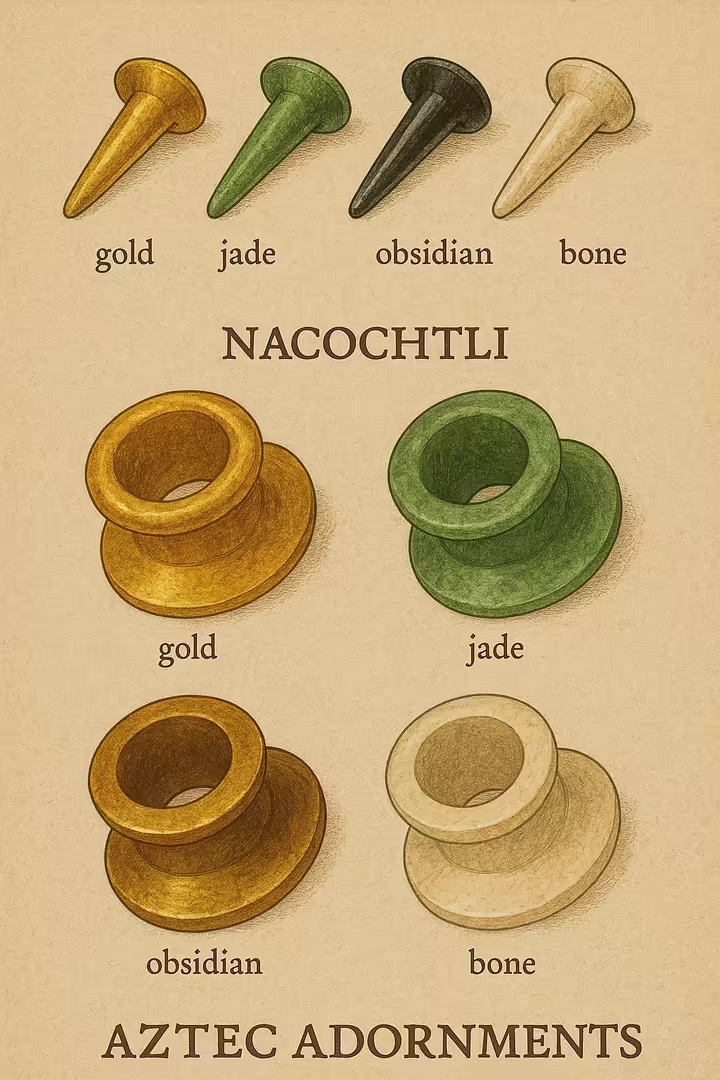

Facial adornments, worn in piercings, were also key markers. The tentetl, or labret, was a plug worn in the lower lip that signified high status and, especially, warrior skill.50

The labret's material clearly showed rank: gold, jade, and rock crystal were for the top elite, while nobles might wear obsidian, and commoners were restricted to bone or wood.50 The labret also had a deeper meaning, it framed the mouth, suggesting the wearer's speech and breath were precious. This was particularly important for rulers, whose title, tlahtoani, means "He Who Speaks," emphasizing the cultural value of authoritative and eloquent speech.50

Similarly, earspools (nacochtli) communicated rank through their material. Gold and turquoise were the most prestigious, while obsidian, pottery, or wood were more common.39

For the nobility, adornment began in infancy when a child's ears were pierced. The lobes were then gradually stretched over a lifetime to fit ever larger and more splendid spools, making the body itself a visible testament to one's inherited elite status.52

Beyond inherited rank, the body became a canvas for displaying earned status, especially for warriors. Progressing from being barefoot to earning sandals, or being awarded a specific labret for capturing enemies, weren't just rewards.37

They were permanent, public declarations of a man's bravery and his service to the state. This system strongly incentivized military service, the main path for commoners to rise socially. Status wasn't just something you had, it was something you became, and this change was physically and permanently marked on the body, turning it into a living record of individual achievements within the empire.

Table 1: Mexica Garment and Adornment Terminology and Social Correlation

| Nahuatl Term | English/Description | Primary Material(s) | Associated Social Class/Rank | Key Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maxtlatl | Loincloth | Maguey fiber, Cotton | All male classes; decoration varied by rank | 12 |

| Tilmatli | Rectangular cloak/cape | Maguey fiber (commoner), Cotton (noble) | All male classes; length, material, and knot style varied by rank | 14 |

| Xiuhtilmatli | "Turquoise cloak"; prestigious blue cape | Dyed cotton | High nobility, Rulers | 40 |

| Huīpīlli | Sleeveless blouse/tunic | Maguey fiber (commoner), Cotton (noble) | All female classes; decoration varied by rank | 39 |

| Cueitl | Wraparound skirt | Maguey fiber, Cotton | All female classes | 1 |

| Quechquemitl | Triangular poncho-like garment | Cotton, Feathers | Noblewomen; Goddess impersonators/priestesses | 1 |

| Cactli | Sandals | Agave fiber, Leather, Animal skin | Nobility, High-ranking warriors, Royalty | 40 |

| Tentetl (Labret) | Lip plug | Gold, Jade, Obsidian (elite); Wood, Bone (commoner) | High-status men, especially warriors | 50 |

| Nacochtli (Earspool) | Ear plug/spool | Gold, Turquoise (elite); Pottery, Wood, Obsidian (commoner) | All classes; material denoted status | 39 |

Power Threads: Special Attire for Ritual and Warfare

Beyond everyday wear, the Mexica created spectacular and deeply symbolic outfits for those wielding military and religious power. In battle and ceremonies, costume wasn't just a uniform.

It was a transformative tool, allowing individuals to shed their human identity and embody state ideology or divine power. These garments, made from the empire's most precious materials, visually represented Mexica might and beliefs.

The Warrior's Wardrobe: Armor and Emblems of Elite Orders

Aztec military clothing was a complex system designed not just for protection, but also to clearly show rank, achievements, and membership in elite warrior groups. The base layer was the ichcahuipilli, or quilted cotton armor.40

This sleeveless jacket, about one to two fingers thick, was made of unspun cotton packed tightly between two layers of cloth.55 When soaked in brine, it became surprisingly good at stopping obsidian-edged blades and absorbing projectile impacts, a testament to Mesoamerican skill in creating effective armor from available materials.1

Over this armor, high-ranking warriors wore the tlahuiztli, a stunning, full-body suit.40 These suits weren't padded themselves but were fabric covered in a mosaic of bright feathers or, for certain merit-based nobles, actual animal skins like jaguar.55

Codices show many tlahuiztli designs, with at least twelve distinct types paid as tribute by conquered provinces, highlighting their value and state control over their production.55 There's a difference between the full-body tlahuiztli and the ehuatl, a tunic or vest worn over armor.

The ehuatl seems to be an older military garment, which in Aztec times was mainly linked with top elites like the tlatoani, often in ceremonial rather than frontline combat roles.57

A warrior's rise through the military ranks was directly tied to how many enemies they captured in battle. This merit-based system offered a way for commoners to advance socially. Each new rank was publicly recognized and rewarded by the emperor with specific, increasingly magnificent costumes and insignia.53

- One Captive: A warrior earned the title Tlamani and received a tiyahcauhtlatlquitl , a mantle with a flower design. 53

- Two Captives: The warrior became a Cuextecatl and was awarded a distinctive tlahuiztli of red and black feathers and a tall, conical cap. 54

- Three Captives: This earned the rank of Tiachcauh ("leader of youths") and the right to wear an ehecailacacozcatl ("wind-twisted jewel mantle") and a prominent back-device in the shape of a butterfly ( tlepapalotlahuiztli ). 56

- Four Captives: A warrior achieved the esteemed rank of Tequihua ("veteran warrior") and was granted the right to wear the ocelototec , the jaguar-style tlahuiztli , and to style his hair in the manner of a veteran. 53

The most prestigious warriors belonged to the elite Eagle and Jaguar societies (cuāuhocēlōtl). Their regalia was the height of military costume, designed to fully embody their symbolic animals. They wore full tlahuiztli of feathers or jaguar skin, and their wooden helmets represented the animal's head, with the warrior's face looking out from the creature's open jaws, as if being consumed.40

Divine Designs: Featherwork, Master Artisans, and Sacred Regalia

Of all Mexica crafts, featherwork, or arte plumario, was considered the most precious. It was an art form reserved for the gods and the highest echelons of society.58

Feathers were valued more than jade or gold, seen as divine expressions, "the Shadows of the Sacred Ones", that brought the color and light of the supernatural world to mortals.60

This sacred art was the exclusive craft of the amanteca, a hereditary guild of specialist featherworkers living in their own district of Tenochtitlan, Amantlan.60 These artisans were incredibly skilled, painstakingly arranging thousands of tiny feathers to create shimmering mosaics.

Their techniques included gluing feathers onto cloth, leather, or paper with a special adhesive from orchid bulbs, and sewing them down with fine thread.58

The materials came from across the empire and beyond. The most sought-after were the long, iridescent green tail plumes of the male Resplendent Quetzal, a bird from the cloud forests of southern Mesoamerica. These feathers were deeply connected with the god Quetzalcoatl ("Feathered Serpent") and with royalty.62

Other prized feathers included the brilliant turquoise of the Lovely Cotinga, the vibrant pink of the Roseate Spoonbill, and the yellow of the Oriole.58 The shimmering, color-changing quality of these iridescent feathers was believed to give objects life, animating them with sacred power as they moved in the light.58

The most spectacular creations of the amanteca were headdresses (copilli) and shields. The famous "Headdress of Moctezuma," now in Vienna, is a stunning example, originally made of nearly 500 quetzal plumes and thousands of other feathers and gold ornaments.61

While often called a "crown," its actual use is debated, it might have been a back-device for a high-ranking warrior or part of a ritual costume for a deity impersonator, rather than something the king wore daily.63

Sacred Vestments: Understanding Priestly Clothing

Priestly attire was specialized to show their sacred roles and devotion to specific deities. While information is scarcer than for warriors, we can piece together a picture of priestly garments from codex illustrations and descriptions.

A common garment for priests was a sleeveless waistcoat that ended above the knees. They were often shown carrying incense bags (copalxiquipilli) and tobacco gourds as part of their ritual gear.44

A key feature of Mexica religion was deity impersonation. During major ceremonies, a chosen priest or participant would be dressed in the full costume and regalia of a specific god, becoming an ixiptla.

In this state, the individual wasn't just representing the deity, they were considered a living vessel for that divine being, a temporary manifestation of the god on earth.66 For example, the costume of an ixiptla for Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl, the wind god, would include a distinctive conical hat of ocelot skin, a prominent red buccal mask shaped like a bird's beak, and a chest ornament made from a conch shell cross-section, the epcololli.66

The lines between religious and military authority often blurred. Men training for the priesthood were also expected to be skilled warriors, earning military honors and costumes just like secular soldiers.

A warrior-priest who captured four enemies, for instance, earned the right to wear a unique black and white conical hat adopted from the Huaxtec people of the Gulf Coast, clearly marking his dual status and high achievement.68

The specialized attire of both warriors and priests was thus a technology of transformation. The wearer of a jaguar tlahuiztli or the regalia of Tlaloc didn't simply represent the jaguar or the rain god, in the heightened context of battle or ritual, they were believed to become that entity.

The costume was a medium for channeling the power, ferocity, and identity of the being it embodied. This reflects a profound aspect of the Mexica worldview, where identity was fluid, capable of being ritually altered through dress.

This transformative power also turned the battlefield into a theater of imperial ideology. The enemy faced not just soldiers, but a terrifying spectacle: a shimmering menagerie of human-animal hybrids and divine avatars, each costume crafted from precious tribute. This psychological warfare, broadcasting the empire's wealth and divine backing, was as crucial to Aztec military strategy as physical conflict.68

Table 2: Warrior Ranks and Associated Regalia (Based on Captive-Taking)

| Number of Captives | Title/Rank | Awarded Garments | Awarded Insignia/Adornments | Key Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tlamani | Tiyahcauhtlatlquitl (mantle with flower design) | Plain macuahuitl and chimalli | 53 |

| 2 | Cuextecatl | Red and black tlahuiztli | Conical cap ( copilli ); right to wear sandals | 54 |

| 3 | Tiachcauh | Ehecailacacozcatl ("wind-twisted jewel mantle") | Butterfly-shaped back device ( tlepapalotlahuiztli ) | 56 |

| 4 | Tequihua | Ocelototec (Jaguar-style tlahuiztli ) | Jaguar helmet; special veteran hairstyle | 53 |

| 5 | (Warrior-Priest) | Green tlahuiztli | Shield with eagle's foot design | 37 |

| 6+ | Cuachicqueh ("Shorn One") | Yellow tlahuiztli | Distinctive shaved hairstyle with one braid | 54 |

Textiles as Tribute: Fueling the Empire

Textiles were the economic heart of the Aztec Empire. Far more than just clothing, woven goods acted as a primary form of money, the most demanded type of tribute, and a direct measure of a household's productivity.

The entire imperial economy, from funding wars to supporting the royal court, relied on textile production, a craft largely in the hands of women.

Weaving Imperial Wealth: Women's Role in the Textile Economy

In Mesoamerica, textile making was the most widespread craft, and it was almost entirely women's work.27 A woman's skill as a weaver was a key measure of her value to her family and community.28

This labor was the foundation of the household economy. Women wove not only to clothe their families but also to create a surplus for sale or trade in busy local markets, and, crucially, to meet the state's constant demands for tribute.24

The economic importance of textiles is clearest in their role as a standardized form of money. Certain types of cloaks, called quachtli, were used like currency.23 Debts, legal fines, and major purchases could all be settled with bundles of these cloaks.

In some calculations, even a human life had a value expressed in a specific number of capes.23 The economic power of female textile labor was so great that it's cited as a main reason for polygamy among the Aztec elite. For a nobleman, more wives meant a larger household textile workshop, generating more wealth for tribute, gifts, and trade.28

The Empire's Demand: Insights from Tribute Codices

The tribute sections of the Codex Mendoza and the Matrícula de Tributos are like the empire's accounting books. They provide an astonishingly detailed record of wealth extracted by the Aztec Triple Alliance from its 39 tributary provinces.4

These pictorial lists, with glyphs for towns and standard icons for goods, clearly show that textiles were, by far, the most common and largest category of tribute demanded.27

The scale of this extraction was enormous. Provinces usually had to make payments twice a year. For example, the Gulf Coast province of Tochtepec had to deliver 1,600 richly decorated cloaks (mantas), 800 striped cloaks, and 400 sets of women's skirts and blouses every six months.69

From the Mixtec region of Coayxtlahuacan, the tribute included 1,200 loads of mantas, plus loincloths and women's tunics.4 Scholar Frederic Hicks, studying these records, estimated that Tenochtitlan received over 32,000 loads of plain fabric and nearly 40,000 loads of decorated cloth each tribute period, a staggering amount of woven wealth.1

These tribute lists also reveal a system of regional specialization that the empire exploited. Specific textile designs were demanded from particular provinces, showing the Aztecs were tapping into established local craft traditions.

Coastal provinces like Tochtepec and Tuchpa, for example, had to provide mantas decorated with conch shell motifs.67 Other highly symbolic garments, like jaguar warrior costumes (ocelototec) and diagonally-patterned nacazminqui cloaks, were also sourced as tribute from specific subject regions.37

This system shows textiles as the "crude oil" of the Aztec economy. They were the essential liquid asset that powered the imperial machine. Their high value for their weight, portability, and universal demand made them a more practical currency than bulky food or indivisible luxury items.

The entire imperial project depended on the constant, massive influx of this woven wealth. This wealth was then redistributed to fund military campaigns, reward loyal nobles, and maintain the lavish lifestyle of the palace court.

Furthermore, the tribute system was a powerful tool for political and cultural integration. By demanding specific, high-status textile designs from conquered provinces, the empire achieved two goals.

First, it seized control over the production of power and status symbols. Second, it co-opted and standardized local identities under a new imperial aesthetic. A distinctive regional design, once paid in tribute, could then be redistributed by the emperor as a reward for service to the empire. This effectively rebranded the garment, erasing its local origin and transforming it into a symbol of imperial generosity and loyalty.37

Table 3: Tribute Textiles from Key Provinces (Codex Mendoza)

| Tributary Province | Geographic Region | Semi-Annual Textile Tribute (Garment Type & Quantity) | Notable Designs | Other Key Tribute Goods | Key Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tochtepec | Gulf Coast (N. Oaxaca / S. Veracruz) | 1,600 decorated mantas, 800 striped mantas, 400 women's tunics/skirts | Richly decorated, striped | Quetzal feathers, cacao, rubber, gold items | 69 |

| Coayxtlahuacan | Mixteca (Oaxaca) | 1,200 loads of mantas (3 styles), 400 loincloths, 400 women's tunics/skirts | Quilted with borders, vertical stripes | Greenstones, feathers, cochineal, gold dust | 4 |

| Tuchpa | Gulf Coast | 800 loads of rich mantas, 800 loads of white mantas with colored borders | Conch shell motif | Chili peppers, cotton | 67 |

| Cuetlaxtlan | Gulf Coast | 800 loads of large white mantas, 400 loads of decorated mantas | Tlaloc motif, Quetzal feather designs | Quetzal feathers, greenstones, turquoise | 4 |

| Ocuilan | Central Highlands (SW of Tenochtitlan) | 400 loads of maguey-fiber mantas | Conch shell motif | Maize, beans, chia, amaranth | 67 |

| Xoconochco | Pacific Coast (Soconusco) | 800 loads of decorated mantas, 400 loads of women's clothing | Jaguar warrior costumes | Cacao, jaguar skins, amber, feathers | 37 |

Colonial Shifts: Unraveling and Reweaving Traditions

The Spanish conquest in 1521 was a cataclysm that deeply disrupted and forever changed the Mexica clothing system. The complex web of meaning, law, and economy woven into Mexica dress was torn apart and re-woven into a new colonial fabric.

This section looks at the new materials, laws, and styles imposed, the scarce but important archaeological evidence, and the lasting legacy of these ancient textile traditions.

New Styles, New Rules: How Conquest Changed Indigenous Dress

The arrival of the Spanish brought new materials, technologies, and clothing norms that radically transformed the indigenous wardrobe. The Spanish introduced sheep, and with them, wool, a fiber unknown in Mesoamerica.20

They also brought silk cultivation and, importantly, the large, stationary treadle loom.29 This European loom was more efficient for producing wide bolts of cloth, and its use in workshops began to shift textile production away from being solely women's work on backstrap looms.29

Indigenous dress started to incorporate European elements, leading to new, mixed styles. The tailored Spanish blusa or camisa (blouse) began to be adopted in some communities, sometimes replacing the traditional huīpīlli.36

New garments like the rebozo (shawl) emerged from this cultural fusion, eventually becoming a powerful symbol of Mexican womanhood.36 Indigenous artisans, especially the amanteca, were co-opted by their new rulers. They began using their exquisite featherworking skills to create Christian religious imagery, like liturgical vestments and devotional panels.58

Crucially, the Spanish dismantled the pre-Hispanic sumptuary system and imposed their own complex, often contradictory laws. These new rules were based not on Mexica ideas of class and achievement, but on the new colonial logic of race and caste (casta).73

Initially, indigenous elites who tried to maintain their status by adopting Spanish dress became targets. Laws were issued prohibiting indigenous peoples from wearing luxurious European fabrics like silk and velvet, and from using potent symbols of Spanish male power, such as swords, daggers, and horses.46

These laws reflected a deep Spanish anxiety about blurring social boundaries in the colonial hierarchy. The conquest thus created a "sartorial rupture," severing the clear, pre-Hispanic link between clothing and social reality. The very meaning of what one wore was thrown into chaos, as an indigenous noble in fine silk was no longer just high-status but a political problem, challenging the new colonial order.

Whispers from the Past: Archaeological Textile Discoveries

Due to the humid climate of the Basin of Mexico, pre-Hispanic textiles, made of organic materials, rarely survive archaeologically.74 This makes the few textile fragments discovered at Tenochtitlan and its sister-city Tlatelolco exceptionally valuable.

Preserved by accidental charring in ritual contexts, these finds provide our only direct physical evidence of Mexica weaving.9

Excavations at Tlatelolco's Temple R, a structure dedicated to the wind god Ehecatl, uncovered an offering with the remains of a sacrificed child. Within this offering were 42 charred textile fragments.9

Analysis revealed at least six different fabric types, including taffeta with brocade (likely from a quechquemitl), basket weave (from a huipilli), and twill (from a satchel). Crucially, these textiles were bundled with a complete set of miniature female weaving tools, including a backstrap loom, ritually linking the sacrificed child with the sacred, gendered role of the weaver.9

At Tenochtitlan's Templo Mayor, a burial found in the elite residential complex known as the House of Eagles yielded 96 charred cotton fragments associated with an adult male dignitary.9

Microscopic analysis identified five different weave types, including highly complex brocades with step-fret and zigzag patterns. The fineness of the cotton threads and the intricacy of the decorative weaves confirmed the high status of the buried individual, as such textiles were legally reserved for nobility.9

While codices are incredibly rich sources, they are post-conquest documents created under Spanish supervision and thus subject to potential biases and artistic conventions.5 The archaeological finds from the Templo Mayor and Tlatelolco, however scarce, represent an unmediated, pre-Hispanic material reality.

The fact that the complex brocade patterns and high-quality cotton found in the House of Eagles burial so closely align with codical descriptions of elite attire provides powerful, independent verification of the historical record. These fragments serve as crucial "ground-truth," confirming that the elaborate clothing shown in manuscripts was not just artistic fancy but a tangible reality for the Mexica elite.

Threads Through Time: Preserving the Legacy of Mexica Textiles

Preserving the few surviving ancient textiles is a formidable challenge for conservators. The work requires painstaking, meticulous processes to stabilize fragile organic materials with minimal intervention.

The typical conservation process involves detailed examination, careful surface cleaning with tools like tweezers and low-suction vacuums, controlled humidification to relax brittle fibers, and consolidation through delicate stitching to support weak areas.77 Objects are then housed in custom-made, acid-free mounts in climate-controlled environments to prevent further decay.77

Despite conquest disruptions and competition from modern industry, threads of the ancient Mexica textile tradition have endured.29 The backstrap loom, the same technology used by women in the Aztec Empire, is still employed by indigenous weavers in many parts of Mexico today.

These contemporary artisans continue to produce cloth echoing ancient techniques and designs, a living link to their pre-Hispanic heritage.20 Garments with pre-conquest roots, like the huipīlli and the sarape (a post-conquest evolution of the cloak), have transcended their origins to become powerful symbols of Mexican national identity.36

Nonetheless, this rich legacy is under threat. It faces pressure from the global market for cheaper, machine-made textiles and synthetic fibers that risk severing the final threads of this ancient and meaningful craft.79

A Legacy Woven in Thread

This report has shown that the Mexica wardrobe was a system of profound complexity and significance, a true microcosm of the empire itself. It was a world built on meticulously processed natural resources, cotton and maguey, whose very selection was dictated by law.

This material was transformed into wealth by a highly skilled, gendered labor force using the traditional backstrap loom. This technology placed enormous economic power in women's hands, even as the state's tribute demands systematically co-opted that power.

Upon this material and economic foundation, the Mexica built a complex social and legal structure using garments and adornments as a public, visual code. This "social text" made the empire's rigid hierarchy immediately legible, reinforcing power and regulating daily interactions.

This system was so central that textiles became the empire's primary currency, the economic lifeblood driving military expansion and political patronage. In war and religion, costume became more than identification, it was a technology of transformation. The spectacular feather-covered tlahuiztli of the warrior and the sacred vestments of the priest were not mere uniforms, they were conduits of power, turning men into avatars of animal ferocity and divine authority.

The Spanish conquest shattered this woven world. It severed the intrinsic link between dress and identity, replacing a system based on class and achievement with a new colonial order founded on race and caste.

Yet, threads of the ancient tradition endured. They persist in rare archaeological fragments from the old capital's heart, in the living crafts of modern indigenous weavers, and in garments that symbolize a proud national identity.

Ultimately, unveiling the Mexica wardrobe is more than cataloging clothing. It is understanding the intricate and inseparable weave of power, belief, economics, and daily life that defined one of Mesoamerica's greatest and most complex civilizations.

Works cited

- AZTEC GARMENTS: FROM BIRTH TO FULFILLMENT by Andrea Ludden University of Texas at Austin Prepared for delivery at the 1997 meeti, https://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/ar/libros/lasa97/ludden.pdf

- Costume and Control: Aztec Sumptuary Laws | catalogued on FRD, https://fashionandrace.org/database/library/costume-and-control-aztec-sumptuary-laws/

- General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de ..., https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667853/

- The essential Codex Mendoza : Berdan, Frances : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming - Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_JQeAQZHev0IC/page/n115/mode/2up?q=boar

- Florentine Codex - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florentine_Codex

- Florentine Codex: Book 8 - University of Utah Press, https://uofupress.com/books/florentine-codex-book-8/

- Florentine Codex - Archaeological and Historical Evidence, http://www.supportingevidences.net/florentine-codex/

- Aztec codices - New World Encyclopedia, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Aztec_codices

- (PDF) Mexica Textiles: Archaeological Remains from the Sacred Precincts of Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329704246_Mexica_Textiles_Archaeological_Remains_from_the_Sacred_Precincts_of_Tenochtitlan_and_Tlatelolco

- Indian Clothing Before Cortés: Mesoamerican Costumes from the Codices - Google Books, https://books.google.com/books/about/Indian_Clothing_Before_Cort%C3%A9s.html?id=5qIFwQEACAAJ

- Everyday Life in the Aztec World. Frances F. Berdan and Michael E. Smith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. 288 pp.; 89 ills. Cloth $99.00; Paper $32.99. ISBN 9780521736220 | West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture: Vol 30, No 1, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/728336

- A Look at Aztec Clothes - Aztec History, https://www.aztec-history.com/aztec-clothes.html

- Basic Aztec facts: AZTEC SOCIAL CLASSES - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/kids/aztec-social-classes

- The Aztec tilmatli or cape - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/artefacts/tilmatli-cape-or-cloak

- The Slave (Chapter 6) - Everyday Life in the Aztec World - Cambridge University Press, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/everyday-life-in-the-aztec-world/slave/5DF79CE2FA0B6F35061DC58AE7B339EB

- A Study on the Cultural Aspects of Aztec Dress, https://her.re.kr/journal/view.php?number=662

- Clothing of Mayans, Aztecs, and Incas | Encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/fashion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/clothing-mayans-aztecs-and-incas

- Life among the Aztecs - The Australian Museum Blog, https://australian.museum/blog-archive/at-the-museum/life-among-the-aztecs/

- Aztec Empire: Simple Clothing, Elaborate Decorations - History on the Net, https://www.historyonthenet.com/aztec-empire-simple-clothing-elaborate-decorations

- Textiles of Mexico - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textiles_of_Mexico

- Mexican Weaving Loom: A Journey into Culture, Craftsmanship, and Tradition - XO-CU, https://xo-cu.co.uk/mexican-weaving-loom/

- Backstrap Loom Weaving: An Ancestral Technique, https://lolomercadito.com/blogs/news/backstrap-loom-weaving-an-ancestral-technique

- (PDF) The economic contribution of women in Aztec society, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364312592_The_economic_contribution_of_women_in_Aztec_society

- The economic contribution of women in Aztec society - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/home/economic-contribution-of-women-in-aztec-society

- About Mexican Textiles | Arizona State Museum, https://statemuseum.arizona.edu/online-exhibit/what-would-frida-wear/mexican-textiles

- Aztecs - Hunter-gatherers data sheet (put reference #:page # after each entry) 2pts each quantitative entry, 1 pt for other, https://dice.missouri.edu/assets/docs/utoaztec/Aztecs.pdf

- Researcher's book on Aztecs focuses not on rulers but on average citizens, https://mexiconewsdaily.com/mexico-living/book-on-aztecs-focuses-on-citizens/

- Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity in Post-Classic Mexico - Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, https://antharky.ucalgary.ca/mccafferty/sites/antharky.ucalgary.ca.mccafferty/files/u1/Spinning_and_Weaving__1991.pdf

- Women and Weaving in Aztec Palaces and Colonial Mexico, https://anth.la.psu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2022/06/Evans_2008ConcubinesandCloth.pdf

- Textiles of Mesoamericanos | UKEssays.com, https://www.ukessays.com/essays/archaeology/textiles-of-mesoamerica.php

- The Evolution Of Aztec Clothing: A Historical Insight, https://deffego.com/the-evolution-of-aztec-clothing-a-historical-insight

- Mexican family preserves ancient dye production method - ICT News, https://ictnews.org/news/mexican-family-preserves-ancient-dye-production-method/

- A resource for teaching cochineal dyeing - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/maya/teachers/cochineal-dyeing-resource

- Cochineal - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cochineal

- Cochineal: Mexico's Red - Harvard Museums of Science & Culture, https://hmsc.harvard.edu/online-exhibits/cochineal1/mexicos-red/

- Traditional Mexican dress · V&A, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/traditional-mexican-dress

- Textiles Recorded: Fashion Reconstructed Through Aztec Codices - UNL Digital Commons, https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1241&context=tsaconf

- Textiles Recorded: Fashion Reconstructed Through Aztec Codices - UNL Digital Commons, https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1134&context=tsaconf

- Aztec clothing - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_clothing

- Aztec Clothing and Dress - HISTORY CRUNCH, https://www.historycrunch.com/aztec-clothing-and-dress.html

- Postclassic Aztec Female Commoner by Kamazotz on DeviantArt, https://www.deviantart.com/kamazotz/art/Postclassic-Aztec-Female-Commoner-332550217

- Aztec Society - World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/845/aztec-society/

- Tilmàtli - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tilm%C3%A0tli

- Aztec Clothing for Kids, https://aztecs.mrdonn.org/clothing.html

- Were there rich and poor in Aztec times? - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/kids/were-there-rich-and-poor-in-aztec-times/1000

- Silks and Swords: Sumptuary Laws and Gender in Colonial Mexico - Portal magazine, https://sites.utexas.edu/llilas-benson-magazine/2022/09/27/silks-and-swords-sumptuary-laws-and-gender-in-colonial-mexico/

- The Mexican manuscript that reveals the wonders of the Aztec world - Apollo Magazine, https://apollo-magazine.com/florentine-codex-mexico-aztec-getty-encyclopaedia/

- What was a Mesoamerican merchant's life like? : r/AskHistorians - Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/1avlop/what_was_a_mesoamerican_merchants_life_like/

- Aztec Daily Life - HISTORY CRUNCH, https://www.historycrunch.com/aztec-daily-life.html

- Labret (y1989-96) - Princeton University Art Museum, https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/33296

- Labret | The Walters Art Museum, https://art.thewalters.org/object/2009.20.249/

- Ear spools (y1989-90 a-b) - Princeton University Art Museum, https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/33227

- Aztec warfare - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_warfare

- Aztec Warriors - HISTORY CRUNCH, https://www.historycrunch.com/aztec-warriors.html

- Costume - Forensic Fashion, http://www.forensicfashion.com/1487AztecWarriorCostume.html

- Aztec Military Costumes - mmgarciablog - WordPress.com, https://mmgarciablog.wordpress.com/2016/05/25/aztec-military-costumes/

- In Mesoamerican military attire/armor, specifically Aztec/Nahua, is ..., https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/7vdr2e/in_mesoamerican_military_attirearmor_specifically/

- Aztec Feather Mosaics of the Old and New World – Feather Mosaics, https://feathermosaics.com/2023/05/01/aztec-feather-mosaics-of-the-old-and-new-world/

- General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex. Book IX: The Merchants. | Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667854

- Aztec Feathers and Feather Art Explained - East India Blogging Co., https://eastindiabloggingco.com/2024/03/24/aztec-feathers/

- The Fight to Bring Home the Headdress of an Aztec Emperor - Atlas Obscura, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/moctezuma-headdress-mexico-austria

- Featherwork , MayaIncaAztec.com, https://www.mayaincaaztec.com/mia-similarities/featherwork

- Moctezuma's headdress - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moctezuma%27s_headdress

- Ultimate headgear - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/aztefacts/ultimate-headgear

- Aztec Codex - Archaeological Institute of America, https://www.archaeological.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Aztec-Codex.pdf

- Clothes Make the God: The Ehecatl of Calixtlahuaca, Mexico, https://journals.flvc.org/athanor/article/download/126712/126265/

- Despite extensive research on Aztec art history, little attention has been paid to Aztec textiles. Given the importance of text, http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/etext/llilas/ilassa/2007/seigler.pdf

- John Pohl's Mesoamerica - The Aztecs pg. 4 - FAMSI, http://www.famsi.org/research/pohl/pohl_aztec5.html

- "Codex Mendoza, Folio 46 recto (p. 99)" by Christopher Pool and Barry Kidder - UKnowledge, https://uknowledge.uky.edu/world_mexico_codices/11/

- Aztec power revealed in the Mexica tribute lists - OER Project Community, https://community.oerproject.com/b/blog/posts/aztec-power-revealed-mexica-tribute-lists

- Traditional Mexican Clothing - Travel Intelligence, https://www.travelintelligence.net/traditional-mexican-clothing/

- Mexican featherwork - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexican_featherwork

- Race, Clothing and Identity: Sumptuary Laws in Colonial Spanish America (Chapter 12) - The Right to Dress - Cambridge University Press, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/right-to-dress/race-clothing-and-identity-sumptuary-laws-in-colonial-spanish-america/DCA35859C89C4A57B8E375EA8E231F18

- TEXTILES AND THE MAYA ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD Gender, power, and status in Classic Period Caracol, Belize, https://www.caracol.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/textiles08.pdf

- Indian Clothing Before Cortes: Mesoamerican Costumes from the Codices (Volume 156) - Goodreads, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1534720.Indian_Clothing_Before_Cortes

- Introduction - Pennsylvania State University Press, https://www.psupress.org/sample_chapter/Saab_introduction.pdf

- Five Years of Conservation Collaboration - MTS, http://museumtextiles.com/textile-conservation/ethnographic-textiles/five-years-of-conservation-collaboration/

- Conservation of a Pre-Columbian Nazca Textile - FIT Institutional Repository, https://institutionalrepository.fitnyc.edu/item/544

- What did the Aztec Wear? - YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YIVSn4Dc8BM