Aztec Fun and Games: A Deep Dive into Their Sports, Pastimes, and Play (c. 1325-1521 CE)

Aztec games were far more than entertainment, they were expressions of culture, spirituality, and social life. From the sacred ballgame Ōllamaliztli, played in grand tlachtli courts, to strategic board games like Patolli and daring aerial rituals like the Volador ceremony, the Aztecs wove meaning into every form of play. This deep dive explores the full spectrum of Mexica pastimes, how they played, why they played, and what their games reveal about their vibrant world. Join us as we uncover ancient rules, divine symbolism, childhood fun, and the legacy these traditions left behind.

Aztec Play: More Than Just Games

Games: A Cornerstone of Mexica Life

In Mexica society, often called the Aztec civilization (c. 1325-1521 CE), games and fun activities weren't just ways to pass the time. They were deeply woven into the very fabric of daily life, touching on culture, religion, politics, and social interactions.1 The Aztecs enjoyed a wide variety of games and pastimes, with something for everyone, no matter their social standing, age, or the occasion.1 Many of these activities had deep religious importance, frequently playing a key role in intricate rituals or stemming from existing spiritual beliefs.1 They even had gods dedicated to these pursuits, like Macuilxochitl (Five Flower), also known as Xochipilli (Flower Prince), the patron of games, music, dance, and feasting.1

The Aztecs seemed a bit wary of too much unstructured "free time," fearing that idleness might lead people down the wrong path towards vice and bad habits.2 Yet, surprisingly, structured games and recreational activities weren't just allowed; they were highly valued and woven into the very core of their culture.2 This might sound contradictory, but it suggests they believed leisure needed a purpose, guided by culturally important and often ritualistic activities, rather than being left to chance. Aztec entertainment, like music, the famous ballgame, board games, dance, sports, and storytelling, was thoughtfully organized. This ensured that even downtime helped reinforce cultural values, deepen religious understanding, or sharpen useful skills. So, the Aztecs didn't avoid leisure; they carefully organized it and filled it with meaning.

Exploring Aztec Pastimes: Our Approach

Here, we're diving deep into the many games, sports, and fun activities of the Aztec civilization, focusing on their peak period from around 1325 to 1521 CE. Our main goal is to understand these activities by carefully looking at their rules as we know them, the objects associated with them, and their huge impact on society, culture, religion, cosmos, politics, and even the economy. To do this, we'll look at evidence like historical accounts from Spanish chroniclers and indigenous writers from the early colonial era, pictures in ancient and colonial-era codices, and artifacts dug up by archaeologists.

We'll also take a critical look at the primary and secondary sources that shape our knowledge of Aztec pastimes, keeping in mind any biases or difficulties in interpretation. We'll try to trace how these activities changed over time, including influences from older Mesoamerican cultures like the Olmec and Teotihuacano. We'll tackle common myths about Aztec games and, when relevant, compare them with how other Mesoamerican cultures, and even other civilizations, played, to see what was shared and what was uniquely Aztec. We're covering not just the big famous games like Ōllamaliztli and Patolli, but also lesser-known activities, kids' games, and ritual shows that all made up the vibrant world of Aztec fun.

Table 1: Overview of Principal Aztec Games and Recreational Activities

| Activity (Nahuatl/Common Name) | Brief Description | Key Material Culture | Primary Participants (Social Class/Gender/Age) | Core Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ōllamaliztli (Ullamaliztli) | Ritual ballgame played with a solid rubber ball, hit with hips, thighs, and sometimes elbows/knees. | Tlachtli (I-shaped ballcourt), solid rubber ball ( ulli ), protective gear (yokes, padding), stone hoops/markers. | Primarily nobility, warriors; professional players. Children of nobility trained. Possible female participation. | Religious (cosmic reenactment, sacrifice), political (conflict resolution, diplomacy), social (status display), gambling. |

| Patolli | Board game of race and chance, played on a cross-shaped mat with beans as dice and pebbles as counters. | Reed mat board ( petate ), beans (dice), pebbles/beans (counters). | All social classes (nobles and commoners), men and women. | Religious (calendrical/cosmological symbolism, divination), social (gatherings, entertainment), economic (heavy gambling). |

| Volador Ceremony | Ritual flight of four men from a tall pole, representing birds, while a fifth plays music atop the pole. | Tall wooden pole, ropes, bird costumes, flute, drum. | Specialized male ritualists (Voladores). | Religious (fertility, cosmic renewal, calendrical symbolism – 52 turns), communication with deities. |

| Xocotl Huetzi Pole-Climbing | Competitive ascent of a tall pole by youths to retrieve an effigy and other goods during a specific festival. | Tall wooden pole, amaranth dough effigy, banners, food items. | Aristocratic male youths. | Ritual (part of Xocotl Huetzi festival), social (display of prowess, competition for status/rewards). |

| Totoloque | Gambling game involving throwing gold pellets to hit a target. | Gold pellets, target. | Nobles (including Moctezuma II), possibly others involved in gambling. | Social (entertainment, gambling), political (played by leaders). |

| Children's Games | Various games including Cocoyocpatolli (hole game), Chichinadas (marbles-like), Mapepenas (hand catch). | Small stones, fruit pits, clay balls, miniature tools (gendered). | Children of all classes. | Educational (socialization, skill development, imitation of adult roles). |

| Music & Dance | Integral to ceremonies, festivals, and entertainment, often with specific costumes and synchronized movements. | Drums (huehuetl, teponaztli), flutes, rattles, conch shells; elaborate costumes. | All social classes, priests, court musicians, dancers. | Religious (worship, ritual accompaniment), social (cohesion, entertainment), cultural transmission. |

| Storytelling/Oral Traditions | Recitation of myths, legends, histories, and poetry, often in performative settings. | (Primarily oral, but linked to pictorial codices). | All social classes, specialized storytellers/poets. | Religious (transmission of beliefs), cultural (history, values), educational, entertainment. |

| Martial Pastimes | Warrior training, mock battles, archery contests, blowgun hunts. | Weapons ( macuahuitl , atlatl, bows, arrows), shields, training grounds. | Primarily males, warriors, youths in training schools ( telpochcalli , calmecac ). | Military (skill development), ritual (mock battles), social (status for warriors). |

| Aquatic Activities | Swimming, canoeing for transport, and likely informal recreation in Tenochtitlan's lacustrine environment. | Canoes ( acalli ), paddles, poles. | All social classes, particularly those living/working on or near water. | Economic (transport, fishing), practical (daily life), likely recreational (swimming for fun). |

| Marketplace/Court Entertainment | Jesters, acrobats (log jugglers), dwarfs performing for rulers; general socializing and revelry in marketplaces. | (Acrobatic props, e.g., logs), musical instruments. | Specialized entertainers for the court; general populace in marketplaces. | Social (entertainment for elite, public diversion), political (display of ruler's power/resources). |

Ōllamaliztli: The Aztecs' Sacred Ballgame

The Mesoamerican ballgame, which the Aztecs called Ōllamaliztli5 (meaning something like "the act of playing the ball game"5), or sometimes Tlachtli1 (the Nahuatl name for its court), was a hugely important and long-lasting ritual sport in the pre-Columbian Americas. This game wasn't new; its history stretched back to at least the 2nd millennium BCE5, with traces found in almost all Mesoamerican cultures.5 For the Aztecs, Ōllamaliztli was much more than just a sport. It was a deeply complex tradition packed with religious, cosmic, political, and social significance.

How Ōllamaliztli Was Played: Rules and Scoring

The main goal in Ōllamaliztli was to keep a solid rubber ball, called an ulli, moving constantly.8 Players, usually in two teams8, could generally only hit the ball with their hips, knees, elbows, or shoulders.1 Using hands or feet was typically forbidden1, which made the game incredibly tough and physically taxing. Teams could have different numbers of players, usually between two and seven on each side.8

Scoring in Ōllamaliztli wasn't simple and seems to have changed over time. The earliest form of the game probably focused on getting the ball to the other team's end of the court7; doing so might even end the game.8 The chronicler Motolinia mentioned that players scored points if the ball hit the wall at the opponent's end.12 Later on, new ways to score emerged, like hitting special stone markers on the side walls of the court.8 Teams could also score points if their opponents made mistakes8, like letting the ball bounce more than twice or hitting it out of bounds.12

Perhaps the most exciting, and maybe the newest, way to score was by getting the ball through stone rings or hoops, called tecainmal in Nahuatl, which were set vertically on the court's side walls.1 Getting the heavy rubber ball through one of these rings was incredibly hard1, and if a team managed it, they often won the game instantly.1 It’s good to remember, though, that not all courts had these rings, especially older ones or those from different regions.1 The game seems to have evolved from a simpler goal of reaching the end zone to this super challenging hoop shot. This change probably made the game more complex and exciting to watch. It also might have boosted its ritual importance, especially if making such a rare shot was seen as a sign from the gods.

The rules and details of the game, even the court design, weren't the same everywhere in Mesoamerica; they changed depending on the region and the era.6 The "hip-ball" game, where players mainly used their hips, was the most common version played on a proper court.14 However, some stories suggest other versions might have allowed players to use their forearms, or even tools like rackets, bats, or handstones.12

The Tlachtli: Building the Sacred Ballcourt

The special place where Ōllamaliztli was played, the tlachtli, had a unique design. Usually, these courts were shaped like a capital 'I', with a long, narrow playing area in the middle.1 On either side were two long, rectangular structures that might have been for spectators or rooms for game-related purposes. The ends of this central alley were the endzones.9 The walls along the playing area could be sloped1 or, sometimes (like at the famous Maya site Chichén Itzá), straight up and down.13

Ballcourts weren't all the same size; they varied a lot. The massive court at Chichén Itzá is the biggest we know of (96.5 meters long by 30 meters wide)9, but Aztec courts were usually smaller, often around 100 to 200 feet (about 30 to 60 meters) long.1 In Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, the main ballcourt was called the teotlachco, meaning "holy ball court."15 These courts were usually built from stone13 and often had smooth plaster floors.9 If they had stone rings, these were often beautifully carved with symbols.1

Where the tlachtli was built in Aztec towns shows just how important it was; it was often one of the first things built when a new area was settled.1 Archaeologists usually find ballcourts right in the ceremonial centers of Mesoamerican sites, close to big temples and burial shrines.9 In Tenochtitlan, the teotlachco was near the royal palace and the Templo Mayor1, supposedly right at the bottom of the great temple's bloody stairs.1 A truly unsettling feature often found near ballcourts was the tzompantli, or skull rack, where the heads of sacrificed people were put on display.1 This careful placement of ballcourts in key ceremonial areas, often next to major religious buildings like the Templo Mayor and linked to strong symbols of death like the tzompantli, clearly shows Ōllamaliztli wasn't just a minor sport. It was a core part of the state's religious and political system, designed to publicly perform, showcase, and strengthen core beliefs about the cosmos and the existing power structures. The huge effort put into building these special arenas, often as a top priority in new towns, also speaks to their vital role in Aztec city and ceremony planning.

More than 1,500 ballcourts have been found all over Mesoamerica6, and some think there might be over 2,300, which shows how widespread and important the game was.14 Big centers like El Tajín in Veracruz even had multiple courts, at least fifteen have been found there!9 Digs have shown these courts weren't just for the ballgame; they were also used for feasts, various rituals, and even other sports like boxing.9 The oldest known ballcourt in the Mesoamerican highlands, found at Etlatongo in Oaxaca, dates all the way back to 1374 BCE, proving the game is incredibly ancient.14 Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) is still doing crucial work discovering and understanding ancient game sites.17

Gearing Up: The Ball, Attire, and Artifacts of Ōllamaliztli

The star of Ōllamaliztli was the ulli or ōllamaloni, a solid rubber ball.1 This rubber came from the latex of the Castilla elastica tree.6 These balls could be quite heavy, sometimes weighing up to 4 kilograms (about 9 pounds)!1 A heavy, solid ball on often-rough courts made Ōllamaliztli a tough and dangerous game.1 Mesoamericans were way ahead of their time in making rubber; we've found rubber balls dating back to 1600 BCE.6 The Olmecs are thought to be the first to make rubber balls. They did this by getting latex, drying it into strips, wrapping the strips around a core to make the ball bigger, and then covering it with a thin latex layer to hold it together and make it bounce.20 People really wanted these rubber balls; records show Tenochtitlan imported over 16,000 of them every year.10

Because it was so dangerous, players wore a lot of protective gear.1 This usually meant loincloths3 and thick leather padding for their hips and thighs.1 Gloves or hand mitts9 and knee pads9 were also common. A special piece of gear, often linked to ballplayers from Veracruz but probably used more widely, was the "yoke" (yugo in Spanish). These U-shaped items were worn around the waist and were likely made of wicker or wood covered in fabric or leather for actual games.9 The many stone yokes found by archaeologists are usually thought to be too heavy for playing and were probably ceremonial versions, maybe used in rituals or as burial gifts.9 Other stone sculptures, called hachas (thin stone heads) and palmas (palm-shaped stones), are believed to have been attached to these yokes, also mainly for ceremonies.9 Helmets sometimes show up in depictions, likely for protection, while fancier headdresses were probably just for rituals.12 The fact that players used specialized, often heavy, protective gear, and faced a real risk of serious injury or even death from the solid rubber ball, shows how physical and high-stakes Ōllamaliztli was. This made the game more than just fun; it was a dangerous show that required great skill, bravery, and stamina from players, who often ended games "bruised and bleeding."1

Ōllamaliztli: A Game of Gods and Cosmos

Ōllamaliztli was deeply woven into how the Aztecs saw the universe and their religion. Many understood it as a symbolic performance of the cosmic order. It represented the ongoing battle between basic opposing forces like life and death, day and night, or light and darkness.6 The tlachtli, the court itself, was often seen as a special, in-between space, standing for the heavens or a pathway to the underworld.9

The ball moving across the court was a powerful symbol for the movements of stars and planets, most often representing the sun's daily trip across the sky and its journey through the underworld at night.6 This sun's journey was often shown as a cosmic fight: the sun, represented by the main Aztec god Huitzilopochtli, against the forces of night, like the moon (Coyolxauhqui) and the stars (the Centzon Huitznahua, Huitzilopochtli's 400 brothers).1 The stone rings on the court might have symbolized sunrise and sunset, or the equinoxes.12 Playing the game was a way to honor the gods, especially sun gods like Huitzilopochtli and gods of farming and rain like Tlaloc.6 Sometimes, players were even shown as if they were these gods, acting out these cosmic stories.6

Myths were key to what the game meant. The Aztecs believed the very first ballgame was played by the gods when the current world, the Fifth Sun, began.8 This story of gods playing first made the human game sacred. The Maya creation story, the Popol Vuh, tells of Hero Twins playing the ballgame against the lords of the underworld (Xibalba), and this is the most detailed myth we have connecting story to the game6, but similar ideas of cosmic battles were part of Aztec beliefs too. The game was also closely tied to ideas of fertility and new life.8 The movements of the sun, moon, and stars, which the game mirrored, were thought to control the seasons and rain, which were vital for good harvests. Decapitation, a common type of sacrifice linked to Ōllamaliztli, was also connected to fertility and rebirth; the Aztecs thought one of three souls was in the head, and offering it could bring renewal.8

Human sacrifice was a grim and common part of Ōllamaliztli.1 Unlike other sacrifices that might involve removing the heart, ballgame victims were often decapitated.8 The severed head, being about the same size and shape as the rubber ball, strengthened this link, and the ball itself was sometimes said to be like a sacrificial head.1 These sacrifices were done to pay back the gods for their original sacrifices that started the universe, to help life continue, and to keep the universe in balance.8 Who exactly was sacrificed, the losers, their captain, or maybe even the winners as a great honor, is still something experts discuss.1

All these deep cosmic meanings of Ōllamaliztli, like heavenly battles, creation stories, farming fertility, and the cycle of life and death, made it a powerful tool for shaping beliefs. When Aztecs played or watched the game, they were taking part in a ritual they thought was crucial for keeping the universe balanced and going. This involvement made people believe more in the state-sponsored religious practices and strengthened the ruler's top role as the main link to the gods. If the game was seen as necessary for cosmic order, then those who organized, paid for, and were good at it, mostly the elite and the state, naturally gained a lot of power and responsibility, which justified and supported their high status in society. The game's strong ties to the Tonalpohualli (the 260-day ritual calendar) and other calendar cycles28, even if not always spelled out for Ōllamaliztli alone, are suggested by its deep ritual character and its job in keeping cosmic harmony, which was itself ruled by the rhythms of the calendar.

Ōllamaliztli: A Game of Power and Status

In Aztec society, Ōllamaliztli was mostly a game for the elite, the nobles (pīpiltin) and rulers.2 Noble children were specially trained in the game from when they were young, often at the high-status calmecac schools.8 Friar Bernardino de Sahagún wrote in his Florentine Codex that by the 1500s, the game had mostly become a "fun activity for the nobility." This hints that some of its older, deeper religious meaning might have faded or at least wasn't stressed as much by this group.22

The game was a place to show off warrior strength and athletic talent, and the athletic sons of nobles were often star players.8 The game's physical challenges and strategic thinking were similar to warfare.25 Gambling was a huge part of the ballgame scene, especially for the elite. Nobles would bet enormous amounts, jewels, expensive goods, slaves, and even their mistresses, on game outcomes.1 Though mostly for the elite, there were also professional ballplayers who weren't nobles. They also gambled heavily, as their living depended on winning.3

Beyond just being a sport with betting, Ōllamaliztli had serious political importance. It was used to settle arguments between rival groups or even whole city-states, acting as a ritual stand-in for war.1 The result of such a game could have major political consequences. On the flip side, a game could also be an excuse for political schemes, like assassinations or attacks.1 Aztec emperors like Ahuitzotl (who ruled from 1486-1502) made Ōllamaliztli a big part of state ceremonies, showing its political clout.6 As a huge public show, the game brought many people together15 and was usually a noisy, lively event that helped build community spirit and shared memories.9

The fact that mostly nobles played Ōllamaliztli, combined with its high-stakes betting and its use in politics and settling fights, shows the game was a key stage for the elite. On this stage, they could show off their wealth, assert their power, and prove their fighting skills, all of which strengthened their high social rank and political control. The possible shift from its deep religious origins to more social and political roles, as Sahagún hinted for the nobility, might mean the game changed to fit the needs of a growing empire. In such a society, showing off status and making political moves became more and more important for elite life.

Patolli: The Aztec Game of Chance, Fate, and the Cosmos

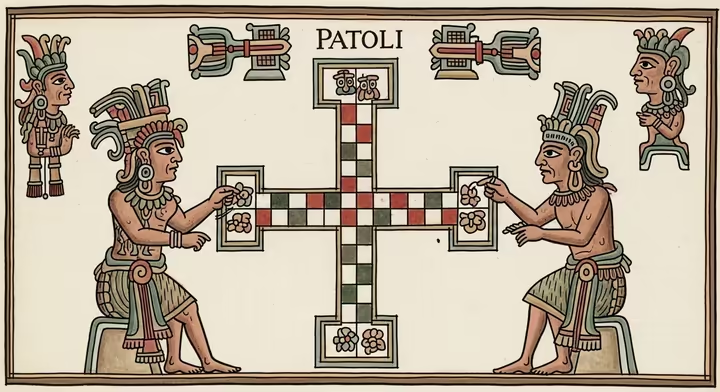

Patolli was another incredibly important and popular game in the Aztec world. It was a game of racing and luck that looked a bit like modern games such as Ludo or Parcheesi.2 But for the Aztecs, Patolli was much more than just fun; it was deeply connected to their economy, social habits, and beliefs about the universe.

Playing Patolli: The Board, Pieces, and Beans

We don't know all the exact original rules of Patolli because no complete native descriptions survived the colonial era.8 However, by piecing together colonial accounts and archaeological clues, we can get a pretty good idea of how it worked. At its heart, Patolli was a race game34, but it also had bits of skill and strategy.1

The game board usually looked like a cross or an "X."1 It was often drawn with black lines on a reed mat called a petate3, using liquid rubber or pine soot for the lines.3 The board had spaces, commonly with four arms, each with 13 squares, making 52 squares in total along the main path.8 Some say boards had around 60 squares.32 It’s worth noting that pictures in codices, while showing the cross shape, might be more symbolic about the number of squares.36 Some squares were special: smaller ones were penalty spots, while rounded ones at the ends of the arms often gave an extra turn.34

Players used colored pebbles, like red and blue, as their game pieces.3 Beans, corn kernels, or even bits of jade could also be used as markers.35 How many pieces each player got depended on how many people were playing: usually six pieces each for two players, five for three, and four for four.34

To move their pieces, players threw "dice," which were usually five large black beans.1 Each bean had a mark on one side, like a white spot or a small hole.3 You got one point for each bean that landed with the marked side up. If all five beans showed their marked side, that was a special throw worth more, often ten points. If no marked sides showed, you scored zero and might lose your turn or get a penalty.34

From what we can piece together, players took turns throwing the beans. You often needed a specific score, like one, to get a piece onto the board, usually on a special starting square.34 Once on, pieces moved based on the bean throw. Some think players picked a direction (clockwise or counter-clockwise) at the start and stuck to it34, while others say movement was always clockwise.35 A big rule was that a piece couldn't land on a square that another piece was already on (whether it was yours or an opponent's, though some versions allowed captures in the middle).34 If you couldn't make a legal move, you usually got a penalty, like paying into a pot or to an opponent.34 Landing on special squares could give you an extra turn or a penalty.34 Some rules even let you capture an opponent's piece if you landed on it in the center part of the board, sending it back to the start.35 To win, you had to get all your pieces around the board and off it, often needing an exact throw for the last square.34 Winning might mean being the first to get all pieces off and taking what was bet in the pot34, or in some versions, winning all your opponent's "point beads" or wagered items.35

These different ideas about the rules, like which way to move, how to capture pieces, and exactly how many squares were on the board, show how hard it is to perfectly recreate ancient games from incomplete old stories and scattered archaeological finds. It really highlights how much interpretation is involved in game history, where experts have to make educated guesses. Some sources flat out say "No-one knows the exact rules"8, and even reconstructions like R.C. Bell's had to add some rules, sometimes from other games.34 This just goes to show that our modern understanding is based on bits and pieces of evidence, which means there could be several believable ways Patolli was played.

Patolli in Stone and Manuscript: Boards and Gear

Archaeologists digging across Mesoamerica have found real proof of Patolli. They've discovered game boards carved into all sorts of things: rocks, plaster floors in buildings17, altars in front of stone monuments (stelae), and even on pottery dishes in graves.36 They've also found small pottery items that might have been game pieces.36 Recently, INAH found nine Patolli carvings on a stucco wall in Campeche, some round and some square, possibly from the Late Classic Maya period (600-900 AD).17 These finds hint that Patolli might have started with boards drawn in the dirt, and later people started carving them into more lasting surfaces.36

Indigenous codices – those amazing picture-filled manuscripts made before and after the Spanish arrived – give us fantastic visual clues about Patolli.

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún's Florentine Codex describes and illustrates Patolli being played with three large beans on a cross marked on a mat. 22 Folio 269r of this codex specifically contains an illustration of the game. 22

- The Codex Mendoza , commissioned around 1541, includes an image on folio 70r identified as an Aztec gambler 3 , and another depiction shows a young Aztec man playing Patolli. 42

- The Codex Magliabechiano , a mid-16th century document, is particularly rich in this regard. Page 048 (also referenced as folio 48r or 70r in different sources/contexts) famously depicts a Patolli game being observed by the god Macuilxochitl or his counterpart Xochipilli. 17

- Other codices, such as the Codex Borgia , show deities like Xochiquetzal (Macuilxochitl's female counterpart) with game boards and bean dice. 3 The Codex Vindobonensis I (Mixtec) also portrays these deities in contexts alluding to games and shows Patolli boards, sometimes with stick dice and carrying cases. 3 The Codex Borbonicus and Codex Vaticanus B also feature depictions of Patolli boards, often of a square type with looping corners and crossed central tracks, which is considered an older style compared to the Aztec cruciform board. 36

The stuff used for Patolli is described pretty consistently. Boards were usually drawn on woven reed mats (petates)3, with liquid rubber or pine soot for the lines.3 The "dice" were almost always beans1, and the pieces were pebbles, beans, corn kernels, or even jade.3

Patolli boards show up in all sorts of materials and places, from carvings in stone in special ceremonial or elite areas to portable mats used by traveling gamblers. This shows how adaptable and common the game was all over Mesoamerica.36 Pictures in codices are often more symbolic than exact diagrams36, but the steady use of the cross shape in Aztec-related codices3 hints that the Aztecs liked this symbolic form, even if the exact number of squares wasn't always the same or as important as the cosmic design. This is different from the older, more varied square-and-loop boards found in other parts of Mesoamerica and in earlier times36, suggesting the Aztecs either preferred this design or standardized it later on.

Patolli's Impact: Society, Culture, and Fortunes

Everyone seemed to enjoy Patolli, from common folks to nobles.1 Even the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II supposedly liked watching his nobles play it at court.18 And it wasn't just for men; women played Patolli too.36

Gambling wasn't just a side thing in Patolli; it was a core part of why people played and loved it.1 Players bet all sorts of things: blankets, maguey plants, food, precious stones, gold jewelry, and in really extreme cases of addiction or desperation, even their homes, families, or their own freedom by selling themselves into slavery.1 The stakes could be incredibly high, and many people got hooked, sometimes betting everything they owned.3 This intense gambling could lead to fights; Sahagún mentioned that "heads were constantly split open," probably talking about brawls over cheating or unpaid bets.32 There were even professional Patolli gamblers who carried their rolled-up mats and game pieces in small cases, traveling around looking for people to play against.3

Patolli games, especially during festivals, were big social events that drew large crowds who also got in on the betting action.3 The Spanish writers, looking at it from their own cultural and religious viewpoint, often looked down on all the gambling. They thought it was foolish and a danger to society.32 Interestingly, the Spanish weren't the only ones worried; Aztec elders also warned about the risks of gambling, and even the Aztec king reportedly tried to control the game. This suggests that Aztec society itself knew it could cause social problems.32 Winning big at Patolli could certainly bring a lot of wealth, but it wasn't officially a way to climb the social ladder like being a successful warrior was.51 Still, winning a fortune could change someone's life for the better, while losing could mean disaster, even becoming a slave.32

The wild gambling in Patolli, where you could get rich quick or lose everything, acted like a shaky economic force in Aztec society. It was a high-risk, high-reward setup that existed alongside, and sometimes clashed with, the more rigid social order. This might show more than just people's love for games of chance. As scholar Inga Clendinnen suggested, it could also reflect the worries of a society very aware of how uncertain life was, where Patolli was a way to test or face one's destiny.32 The fact that both Aztec and later Spanish leaders tried to control or stop the game shows how powerful and potentially damaging it could be to people and society. Patolli was definitely more than just a simple game; it was a social event with real economic effects that could drastically change lives and shake up the usual way of things.

Patolli: A Game of Gods and Prophecy

Patolli was packed with religious and cosmic meaning. The main god of the game was Macuilxochitl (Five Flower), also called Xochipilli (Flower Prince). This god was in charge of games, music, dance, flowers, pleasure, and even fate and going overboard.1 Gamblers would call on Macuilxochitl before playing, hoping for good luck3, and sometimes they made offerings to the god during the game.35

Patolli had a vital link to the Mesoamerican calendar system. The usual board setup with four arms, each having 13 squares, made a track of 52 spaces. This perfectly matched the 52-year cycle, known as the Aztec "century" or calendar round (xiuhmolpilli).1 Each square on the board could represent a year in this important cycle.36 This calendar connection gave the game a feeling of cosmic time.

Patolli boards were also often lined up with the main directions (north, south, east, west), suggesting the game mat itself stood for the flat earth.36 This cosmic setup was similar to the ritual ballcourt, which was also seen as a model of the cosmos. Experts have pointed out amazing similarities between Patolli and Ōllamaliztli. These include having the same patron gods, the playing area divided into four parts, the presence of gambling, and saying prayers or doing rituals before playing.36 The Nahuatl word ollin, which means "movement" and "rubber" (used for the ballgame ball and sometimes to draw Patolli boards), is an important day sign in the calendar. This word further links both games to ideas of cosmic movement and change.36 Seeing the ollin symbol in the middle of some older Patolli board pictures in Mixtec codices makes these cosmic and calendar connections even stronger.36

Besides its calendar and cosmic symbols, Patolli seems to have been used to tell fortunes or predict the future.36 Playing the game, especially when betting big, was seen as a way to test your fate or destiny. The large bets weren't just reckless; they could be seen as "acts of devotion," showing the player's faith and trust in the gods or the powers of destiny.32

Patolli's deep connection with the Aztec calendar, especially the 52-space track matching the 52-year cycle, and its link to Macuilxochitl/Xochipilli, a god not just of games but also of fate, pleasure, art, and even dangerous overindulgence52, turned the game from simple fun into a mini-performance of how Aztecs saw time, destiny, and the gods' influence. Playing Patolli was like directly interacting with the basic forces and repeating patterns they believed controlled their lives and the universe. The game offered a hands-on, interactive way to feel and think about these deep ideas.

Sky Dancers and Pole Climbers: Aztec Aerial Rituals

Some of the most stunning and meaningful recreational and ritual activities in Mesoamerica involved performances high up on tall poles. The Aztecs had both the ritualistic Volador ceremony and a competitive pole-climbing event during the Xocotl Huetzi festival.

The Volador Ceremony: Dance of the Flyers

The Danza de los Voladores, or "Dance of the Flyers," also called Palo Volador ("Flying Pole"), is an ancient Mesoamerican ceremony. It's still performed today, though in different ways, especially by the Totonac people of Veracruz. But it has ancient roots and was practiced by many groups, including Nahuatl-speakers like the Aztecs.8

Usually, five men take part in the ceremony.8 Four of them are the voladores (flyers), often wearing fancy bird costumes.8 The fifth is the caporal, a musician and dancer who stays at the top of the pole.8 For example, Totonac volador outfits include red pants, a white shirt, an embroidered chest piece (for blood), and a special cap with flowers (for fertility), mirrors (for the sun), and colorful ribbons (like a rainbow).40 Traditionally, only men did this ritual, but some Totonac communities now let women join after special purification ceremonies.40 The flyers were thought to be acting as different birds like parrots, macaws, quetzals, and eagles, which could represent gods of earth, air, fire, and water.40

The main piece of equipment is a very tall wooden pole, anywhere from 18 to 40 meters (about 60 to 130 feet) high.8 At the very top, there's a small platform called a manzana (apple) and a spinning square frame called a cuadro.40 Long ropes are wrapped around the pole and tied securely to the flyers' ankles or waists.8 The caporal has a flute and a small drum, and he plays music throughout the ceremony.8

The ritual starts with the caporal and the four voladores climbing the pole. When they reach the top, the caporal stands on the tiny platform, playing his instruments and dancing, often turning to face the four main directions and the sun.8 After this, the four flyers jump headfirst from the platform "into the void."53 As the ropes unwind, the cuadro spins, and the flyers come down in bigger and bigger circles, like birds flying, until they softly land on the ground.8

Flying with Meaning: The Volador's Cosmic Connections

The Volador ceremony is full of cosmic and religious meaning. It's basically a fertility dance or ritual, done to show respect for and harmony with nature and the spirit world. It's also meant to please the gods and bring good fortune, especially rain for good harvests.40 Totonac myths, for instance, say the ceremony started during a bad drought, when the ritual was invented to beg the gods for rain.40

When the caporal greets the main directions and the sun, it shows the ceremony's link to sun worship and ideas about space and the cosmos.8 The pole itself is often seen as an axis mundi or world tree, a symbolic link between the sky, the earth, and the underworld.40

A really important symbolic part of the ceremony is its connection to the calendar. Each of the four flyers usually makes thirteen turns around the pole as they come down. If you multiply that (4 flyers x 13 turns), you get 52 turns.8 The number 52 is super important in Mesoamerican calendars. It stands for the 52-year cycle, often called the "Aztec century" or xiuhmolpilli ("tying together of years"). This is how long it takes for the 260-day ritual calendar (Tonalpohualli) and the 365-day solar calendar (Xiuhpohualli) to line up again.55 This complex calendar symbolism shows the ceremony's job in marking and making holy the passing of major time periods. Every time the Volador dance is performed, it's said to bring the story of the universe's birth to life, representing the world being recreated and life being renewed.40

Reach for the Sky: The Xocotl Huetzi Pole Climb

Different from the Volador ceremony, but also using a tall pole, was a competitive pole-climbing contest. This happened during the Aztec festival of Xocotl Huetzi ("Falling Fruit" or "Fruit Which Falls"), which honored Xiuhtecuhtli, the fire god.3 It was a yearly competition for young Aztec men.3

A super tall tree, about 110 to 140 feet (around 33 to 42 meters), was chosen, had its bark removed, was smoothed down, and made holy. This pole was then put up in the main courtyard of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan.3 At the very top, they placed a bird figure called the Xocotl image, made from amaranth seed dough. Other nice things like flowers, banners, and a warrior's shield were also put up there.3

The competitors were young noblemen, often described as the sons of lords and chiefs, who were keen to show off their skill, bravery, and quickness.3 After religious ceremonies, which often involved human sacrifices, the competition started. The young men would race up the pole, trying to be the first to get to the top and grab parts of the bird figure and the other "goodies."3 Both Sahagún and Durán wrote about and drew this festival and its pole-climbing contest.3

Some experts, like Gertrude Kurath, Samuel Martí, and Guy Stresser-Péan, think there might be connections or evolutionary links between the Volador ceremony and the pole rituals of the Xocotl Huetzi festival.55 Both use a sacred pole, involve climbing, and relate to ideas of fertility and cosmic renewal. But there's a big difference: the Xocotl Huetzi event was clearly a competition for prizes and status3, while the Volador was a ceremony about ritual flight and calendar symbols.8 Fray Diego Durán, in his writings, seemed to see them as different, apparently thinking of the Volador as more of a game, though not everyone agrees with this.55 The Xocotl Huetzi pole climb was all about competitive climbing and getting material rewards. The Volador ceremony, on the other hand, was about ritual flight and deep calendar and cosmic symbolism. This suggests that even though both traditions used a central pole and had aerial parts, they served different social and ritual purposes in Aztec society. One highlighted youthful skill, competition, and actual prizes, while the other was for cosmic renewal, talking to gods, and confirming the cycles of time.

Did the Mexica Practice the Volador? Yes!

Even though the ceremony is strongly linked to other Mesoamerican groups, especially the Totonac, there's strong proof that the Volador ceremony, with all its deep calendar and cosmic meaning, was also done by and very important to the Mexica (Aztecs). The Aztecs themselves apparently thought the Danza de los Voladores was a symbol of their own culture.40

Guy Stresser-Péan suggested that a "classic or Aztec" version of the Volador dance, with a caporal and four flyers, started in the Valley of Mexico in the 1300s.55 Stories from people who were there during the conquest support this. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of Cortés's soldiers, described dancers at Moctezuma II's court who seemed to "fly" when they danced ("vuelan cuando bailan por lo alto").55 Fray Diego Durán told a story about an Aztec prince named Ezhuahuacatl who sacrificed himself by diving from a high pole, which sounds a lot like the Volador flyers.40

Most importantly, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, in his Calendario y Arte divinatoria (part of his Florentine Codex work), clearly mentions the palo volador ("flying pole") and its symbolism tied directly to the Aztec calendar. He explains how the four dancers each making thirteen turns adds up to 52 turns, representing the 52-year cycle of the Aztec calendar round or xiuhmolpilli.55 This detailed description from Sahagún, linking the ceremony straight to key Aztec calendar ideas, pretty much disproves claims that the Volador wasn't really an Aztec thing or was only done by other groups like the Totonac.53 All this evidence confirms that the Volador ceremony was definitely an important part of Mexica ritual life.

More Ways Aztecs Had Fun: A Look at Other Pastimes

Besides the big shows of Ōllamaliztli and the deep rituals of Patolli and the Volador ceremony, Aztec society had lots of other ways to have fun. These activities suited different ages, social groups, and events. They included games of skill and luck, warrior training, kids' games, and lively performances.

Totoloque: Aiming for Gold (and Fun)

Totoloque was a popular gambling game in central Mexico when the Aztecs were around.1 The idea was to throw or flick small pellets, supposedly made of gold, to hit a specific target.1 We don't have a lot of details about the exact rules or what the target looked like, but it was clearly a game of skill that involved aiming and betting.

A really interesting story about Totoloque comes from the Spanish writer Bernal Díaz del Castillo. He wrote that the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II played this game with Hernán Cortés while Cortés was staying in Tenochtitlan.1 This little historical detail is quite telling. The fact that the top leader of the Aztec Empire played a gambling game with the head of the Spanish conquistadors, during a super tense time of political and cultural clash, means Totoloque wasn't just a silly game. It probably acted as a way for them to socialize, even though they were from totally different worlds and in a tricky situation. Playing together might have opened doors for casual diplomacy, sizing each other up, or just a structured way to hang out without all the stiff political formalities. For Moctezuma, it could have been a way to figure out Cortés's personality, and for Cortés, it might have been a chance to build a connection or see the emperor when he was more relaxed.

Growing Up Aztec: Kids' Games and Learning

Childhood in Aztec society was all about structured learning and fitting into how things were done, and kids' games and toys were a big part of that.59 It wasn't just mindless play; these activities were meant to bring children into the community, often by having them copy adult jobs and duties. This helped them develop important physical, mental, and social skills.59

Toys were often tiny versions of adult tools, and they showed and strengthened expected gender roles from a very young age.8 The Codex Mendoza tells us that boys usually got mini weapons and farming tools, hinting at their future as warriors and farmers. Girls, on the other hand, got smaller versions of things for house chores, like weaving tools, getting them ready for household duties.8 Dolls, maybe made of clay, were common for girls8, and small bow and arrow sets were for boys.8 Whistles were popular with both boys and girls.8 Archaeologists have found small animal figures with wheels, and they used to think these were kids' pull-toys. Now, they believe they were more likely ritual items or special burial gifts, because they're often found in perfect condition.8 We don't see much direct proof of Aztec kids playing with spinning tops (trompos) in these sources, though spinning fabric was a key skill taught to girls64, and tops are ancient toys found all over.65

Aztec kids played all sorts of games, even if we don't know all the exact rules for them:

- Cocoyocpatolli , or the "hole game," involved children competing to toss small stones or fruit pits into a designated hole from a certain distance. 60

- Chichinadas , a name derived from the Nahuatl word meaning "to hit," was a game described as being very similar to marbles. 60

- Mapepenas , translating to "hand catch," was a game where a stone of a particular color was chosen, with more stones hidden on a mat. The winner was the first player to find another stone of the same chosen color. 60

- More generally, children played games that sound a bit like modern Jacks or Marbles.8 For example, they might throw small balls along the ground towards another ball in the center, or toss a small stone in the air to try and hit clay balls, stones, or seeds laid out on a mat.8

The big focus on gender-specific toys and games that copied adult activities shows a very organized and practical way of socializing kids in the Aztec world. This system wasn't mainly about encouraging free-flowing imaginative play. Instead, it was about effectively guiding children into the set economic and social roles they were expected to take on as adults. Through this kind of play, children started learning practical skills and taking in Aztec society's values and expectations from a very young age. This helped ensure that roles and responsibilities were passed down through the generations.

The Soundtrack of Aztec Life: Music, Dance, and Stories

Music, dance, and storytelling were lively and essential parts of Aztec fun and ritual. They were powerful ways to express culture, show religious devotion, and bring people together.2

Music was super popular and had many sides to it.1 It wasn't just for fun; it was also a way to pass on cultural knowledge, share religious ideas, and build emotional ties to life events and nature.2 Sacred songs were written and performed to remember what rulers did, celebrate the empire's history, and honor the gods, with many songs telling stories of the gods.2 Aztec musical instruments included various drums (like the upright huehuetl and the horizontal log drum teponaztli), rattles, flutes, and even simple percussion from pebbles and sticks.2 Music was played in all sorts of places: from worship at home and local parties to big ceremonies at the temple and fancy shows by court musicians who lived in the palace and entertained the ruler and rich merchants.69

Dance was a very common and advanced art form, sometimes called "singing with their feet."2 Dancers often wore special traditional outfits and did complex, coordinated moves.2 A lot of Aztec dance was ceremonial, for the gods, and full of deep spiritual, cultural, and religious meaning.2

Spoken traditions, like storytelling, were crucial for the Aztecs. They used them to pass their religious beliefs, myths, and historical legends down through generations.2 Stories were told during important social events like feasts, banquets, ceremonies, and other get-togethers.2 The Aztecs had fancy forms of theater with amazing shows involving costumes, music, dance, and dramatic storytelling. These were all designed to honor gods, celebrate harvests, and connect people with the spirit world.68 These shows weren't just entertainment; they were essential parts of life before the Spanish arrived.68

Music, dance, and storytelling were so closely linked in Aztec culture that they probably weren't seen as separate arts, but as connected performance traditions. They worked together to create powerful, engaging experiences that told complex cultural stories, strengthened religious beliefs, and built a shared sense of identity and community involvement in the sacred and social life of the empire.

The Warrior's Path: Training, Combat Sports, and Ritual Battles

Since Aztec society was very focused on war, and warfare was key to its growth and religious beliefs, warrior pastimes and training were common and very organized. Training for war started in childhood. Young boys went to special schools like the telpochcalli (for commoners, teaching warrior skills) and the calmecac (for nobles, training for priesthood or top military/government jobs).71 This training was tough. It included hard physical work from a young age, lessons in history and religion, and thorough coaching in fighting, using weapons (like the obsidian-bladed macuahuitl, bows and arrows, and the spear-thrower or atlatl), and battle tactics.71 Music, especially drumming, was apparently used to give commands during training and in battle.71

The Aztecs probably had good hand-to-hand fighting skills for when warriors were unarmed, but there's no solid proof they had formal "martial arts" like we think of them today.71 Instead, they focused on being effective in battle, being disciplined, and capturing enemies, which was a main way to get promoted in the military and move up in society.71 Elite warrior groups, like the Eagle Warriors (cuāuhtli) and Jaguar Warriors (ocēlōtl), had high-status jobs, special duties, and unique outfits.72

Ritual battles and practice fights were also part of Aztec fun and ceremonies, sometimes seen as entertainment.1 For example, they had mock battles using net bags filled with soft things like flowers or wool during a religious festival for the goddess Ilama Tecutli.3 These events were playful but could still get rough, and they helped teach warrior values and let people blow off steam. The fact that warrior training and ritual fights were so constant and deeply part of life, from school days to being in elite adult groups, shows a culture where fighting skill was vital for the empire's goals. It was also tied to a person's status, religious faith (especially to the war god Huitzilopochtli), and the basic setup of the state.

Making a Splash: Water Life in Tenochtitlan

The Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, was an amazing piece of engineering, a city built on an island in Lake Texcoco. This watery environment really shaped Aztec life, making water skills and activities super important.73 Canoes (acalli, which means "water-house" in Nahuatl) were the main way to get around. They were essential for moving goods to and from the city's busy markets (like the huge market at Tlatelolco), for getting rid of waste, and for moving troops.73 There was a ton of canoe traffic; some guess there were 100,000 to 200,000 canoes on Lake Texcoco when the Spanish showed up.75 These boats came in all sizes, from everyday canoes about 14 feet long (dug out from single tree trunks) to giant cargo canoes over 50 feet long that could carry 60 people or three tons of corn.75 They were moved with wooden poles or paddles, and the idea of poling was said to have been invented by Opochtli, a god of hunting and fishing.75

Spanish writers like Bernal Díaz also said the Aztecs were great swimmers. Both men and women were supposedly "as much at home in the water as on land."77 Kids were taught to swim as soon as they could walk. Swimming wasn't just practical; it was also for fun and thought to be good for health, kind of like hydrotherapy.77

We know for sure that boating and swimming skills were vital in Tenochtitlan, and that people swam for fun. But the old sources don't really talk about organized water sports like swimming races or boating games in the same detail as Ōllamaliztli or Patolli. Still, with water everywhere and so many people good at canoeing and swimming, it's very likely they had casual water fun, like spur-of-the-moment canoe races or showing off swimming skills. Their deep connection to the lake, which they needed for food, trade, and defense, would naturally have made them comfortable with water, and that probably carried over into fun activities. Maybe these weren't turned into big public shows or super ritualistic events like the main land games, or perhaps the chroniclers just didn't write about them because they were more focused on the flashier or more ritual-heavy stuff.

Fun for All (and the Elite): Markets and Court Shows

Aztec public life had different kinds of fun, both in the busy marketplaces (tianguis) and in the more private world of the ruler's court. Big marketplaces, like the one in Tlatelolco (Tenochtitlan's neighbor city), weren't just for buying and selling. They were also lively social spots where people met to chat, gossip, and just walk around watching everything.78 Some experts, using Mikhail Bakhtin's ideas about carnival, think these marketplaces, where everyone mixed and was somewhat anonymous, might have also been places for "anti-establishment talk." People could make fun of things, ridicule, and party in ways that might question the official leaders.78 The old sources don't specifically say there were regular formal entertainers in the marketplaces for everyone, but the "carnival" feel suggests that casual shows, music, or other spontaneous fun could have easily happened.78

The Aztec court, especially the palace of the tlatoani (ruler), had more formal entertainment. Rulers and nobles watched shows by different entertainers, like jesters, acrobats, and dwarfs.3 These shows often happened during banquets and had music from talented court musicians.69 One of the most amazing acrobatic acts was log juggling. Acrobats would lie on their backs and expertly handle a big, heavy log with their feet, tossing it up and making it "dance."3 Sahagún said these acts were both "funny and wonderful."3 This kind of court entertainment wasn't just fun for the elite; it also showed off the ruler's power, wealth, and ability to gather talented people and resources from all over the empire. Having special entertainers and musicians made the court seem grander and more prestigious, boosting the ruler's high status.

Understanding Aztec Games: Clues from the Past

What we know about Aztec games and fun comes from a mix of firsthand historical accounts, native picture books (codices), and things dug up by archaeologists. Each type of evidence gives us unique clues, but they also come with challenges, like built-in biases and the fact that a lot of stuff hasn't survived.

Reading Between the Lines: Spanish Writings and Indigenous Codices

Right after the Spanish arrived, some incredibly valuable documents were created. Spanish friars, and sometimes native authors, wrote down details about Aztec life.

Spanish Chroniclers:

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: His huge work, the Florentine Codex (originally La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España ), was put together between 1545 and 1590 with help from Nahua elders, artists, and former students. It's probably the most complete source we have on Aztec culture. 3 It's split into twelve books covering religion, how they saw the universe, society, economy, nature, and the story of the conquest. Book VIII, "Kings and Lords," specifically talks about the habits and fun activities of the nobles, with descriptions and pictures of Patolli and Tlachtli (Ōllamaliztli). 22 Sahagún's clear goal was to understand native religion and customs to help spread Christianity. 50

- Fray Diego Durán: Author of the History of the Indies of New Spain (also known as Book of the Gods and Rites and the Ancient Calendar ), Durán was born in Spain but grew up in Mexico and spoke Nahuatl fluently. 3 His work, based on a Nahuatl chronicle that's now lost and interviews with Aztec people, gives lively descriptions of elite court life, how commoners lived, daily habits, and various games. He talks in detail about the rubber ballgame (hipball), Patolli, and another dice game played with split reeds. 3 Durán often admired how clever Aztec games were but also criticized them, especially all the gambling that went with them. 3

- Other Chroniclers: Several other Spanish observers gave valuable, though sometimes briefer, accounts. Bernal Díaz del Castillo mentioned Moctezuma II playing Totoloque with Cortés 1 and saw Volador-like shows at Moctezuma's court. 55 Motolinia (Fray Toribio de Benavente) wrote about how Ōllamaliztli was scored. 12 Juan de Torquemada and Francisco Javier Clavijero later wrote about the Volador ceremony, using earlier sources and spoken traditions. 55

Indigenous Codices:

These pictorial manuscripts, mostly created in the early post-conquest period often under Spanish supervision and with Spanish annotations, are vital visual sources.

- Codex Mendoza (c. 1541): Ordered by Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, this codex was made by native artists and writers. 3 Its third part (folios 56v-71v) shows pictures of daily Aztec life, including scenes of birth, kids' chores and punishments, how young people were taught for military or priest roles, and marriage. 59 It also has a picture of an Aztec gambler or Patolli player. 3

- Codex Magliabechiano (mid-16th century): Mainly a religious document, it shows gods, native rituals, costumes, and beliefs about the cosmos. 17 Importantly for us, page 048 (folio 48r/70r) shows a Patolli game being watched by the god Macuilxochitl (or Xochipilli). 17 The codex has Spanish notes that help us understand its pictures. 43

- Other Codices (e.g., Borgia, Vindobonensis I, Borbonicus, Vaticanus B): These codices, some older than the Aztec empire or from nearby cultures like the Mixtec, have pictures of Patolli boards (often the older, square "Type I" with corner loops, different from the Aztec cross-shape) and related gods like Macuilxochitl and Xochiquetzal. 3 These show the wider Mesoamerican background and age of these games.

Addressing Biases and Interpretive Challenges:

We have to be careful when looking at these sources. The Spanish writers, especially the friars, wanted to convert people to Christianity. So, their descriptions of native customs were often biased, as they tried to find and get rid of what they called "idolatry."50 As a result, games with strong religious or fortune-telling connections were often criticized or not understood properly. They also tended to describe Aztec games and rituals by comparing them to things Europeans knew, Patolli was "like dice,"22 Ōllamaliztli was a "ball game," and Alquerque (an Aztec strategy game) was like checkers.3 This way of comparing, while meant to make strange things understandable to Europeans, often made things too simple or twisted the real native meanings and cosmic depth of these activities. Likewise, things like gambling were often judged by Christian morals.32 Even the codices made after the conquest, though often drawn by native artists, were usually ordered and overseen by Spaniards. This could affect what was in them, how they looked (like being bound like European books instead of traditional folded screens), and the notes written with them.87 Today's experts have to work hard to see past these colonial viewpoints and compare texts, pictures, and archaeological finds to get a more balanced and real understanding of Aztec games and fun.

Table 2: Key Ethnohistorical Sources on Aztec Games and Pastimes

| Source | Relevant Games/Pastimes Documented | Key Insights Provided | Noteworthy Interpretive Considerations/Biases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Florentine Codex (Sahagún) | Ōllamaliztli (Tlachtli), Patolli, Xocotl Huetzi pole-climbing, archery, blowgun hunts, log juggling, court entertainment. | Rules (basic), equipment, participants (nobility), cosmological links (Ōllamaliztli initially), gambling (Patolli). Also describes festivals and noble pastimes, with illustrations by Nahua artists. | Goal was evangelization (understanding "idolatry" to remove it). Focus on nobility for some games; descriptions can be seen through a European filter. |

| History of the Indies of New Spain (Durán) | Ōllamaliztli (hipball), Patolli, Totoloque, an unnamed dice game (split reeds), "pins" (bowling-like), Alquerque (checkers-like), Xocotl Huetzi pole-climbing, mock battles. | Detailed descriptions of how games were played, what players wore, gambling (very high stakes), professional players, social setting (nobles and commoners played). Also mentions religious calls to Macuilxochitl and festivals. | Based on a lost Nahuatl chronicle and informants. He admired how complex the games were but was critical of gambling and "pagan" aspects. Native ideas might be reinterpreted. |

| Codex Mendoza | Patolli (gambler shown), children's activities/education (copying adult roles), warrior training, priest duties, palace life. | Shows a picture of a Patolli player, daily life routines, how children were socialized, and social structure. Has Spanish notes. | Ordered by the Spanish viceroy for the Spanish King. Native artists but Spanish oversight. Focuses on tribute, government, and "daily life" for colonial understanding. |

| Codex Magliabechiano | Patolli, associated deities (Macuilxochitl/Xochipilli). General religious rites, cosmology. | Picture evidence of a Patolli game with a god watching. Spanish comments help with interpretation. Part of the Magliabechiano group, based on a lost original. | Mainly a religious document. Made after the conquest on European paper. Comments reflect colonial-era understanding. |

| Bernal Díaz del Castillo (True History...) | Totoloque (played by Moctezuma & Cortés), Volador-like performances at court. | Eyewitness accounts from a conquistador. Gives context for games in high-level interactions. | A soldier's viewpoint, not a systematic study of culture. Focuses on events related to the Conquest. |

Digging for Clues: What Archaeology and INAH Tell Us

Archaeology gives us vital physical evidence that adds to, and sometimes questions, what we learn from texts and pictures.

- Ballcourts ( Tlachtli ): Finding over 1,500 to 2,300 formal ballcourts across Mesoamerica shows how old and important the game was.6 The oldest confirmed highland ballcourt, at Etlatongo, Oaxaca, goes back to 1374 BCE!14 Court designs changed by region and time, but the I-shape was common,9 and they were usually built of stone and plaster.9 We don't have tons of specific details on Tenochtitlan's teotlachco or the courts in Tlatelolco from these quick mentions, other than that they existed near big temples1, but we know for sure they were right in the heart of the Aztec capital.

- Patolli Boards: Archaeological proof for Patolli includes game boards carved into different surfaces like rocks, plaster floors of buildings, altars, and even pottery found in graves.17 These finds show different board styles, from the cross-shape the Aztecs liked to older, square or rectangular boards with corner loops common in other areas, especially among the Maya.36

- Game Artifacts: Key items include solid rubber balls; the oldest ones (around 1600 BCE) were found at the Olmec site of El Manatí.6 Parts of ballplayer outfits, especially ceremonial stone versions of yokes, hachas , and palmas , have also survived.9 For Patolli, small pottery or stone objects thought to be game pieces have been found.36

- Contributions of INAH: Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) is super important for ongoing archaeological research and preservation. For example, INAH archaeologists recently found nine ancient Patolli game boards in Campeche, probably Maya.17 This kind of work constantly improves our understanding of how widespread, old, and varied these games were.

What archaeologists find often backs up details from texts and pictures, like how common ballcourts and Patolli boards were. But archaeology also often shows these games were around for much longer and varied more by region than you'd think just from Aztec-focused colonial stories. For instance, the different Patolli board styles found across Mesoamerica, some hundreds of years older than the Aztecs, are different from the more standard cross-shape shown in Aztec-era codices. This hints that the Aztecs took on and changed long-held traditions, and that colonial writers might have oversimplified this complex history by focusing mainly on the Aztec view.

Games Through Time: Aztec Inheritance and Innovation

The Aztecs inherited a rich tradition of games and rituals from the Mesoamerican civilizations that came before them.

- Olmec (c. 1400-400 BCE): Many credit the Olmec with starting key parts of Mesoamerican civilization, including the ritual ballgame.6 The oldest known ballcourts (like Paso de la Amada, c. 1400 BCE) and the earliest found rubber balls (El Manatí, c. 1600 BCE) are linked to the Olmec homeland or areas they influenced.6 We're less sure where Patolli started, but it was in Teotihuacan by 200 BCE,44 which means it had a long history before the Aztecs, maybe with even earlier, unknown roots.

- Teotihuacan (c. 100 BCE - 750 CE): This great city was a major cultural and political power in Classic Mesoamerica and had a big impact on later civilizations, including the Aztecs, who saw it as a place of origins.99 Archaeological finds and pictures from Teotihuacan show they played the ballgame; rubber balls have been found, along with a possible ballcourt marker, and murals in the Tepantitla area show different kinds of ballgames, including hip-ball and games with sticks.12 Patolli boards from the Teotihuacan era have also been found.1

- Aztec Adaptation and Elaboration: The Aztecs inherited these existing games and added their own cultural touches.1 For Ōllamaliztli, they continued its deep ritual and political importance, maybe even beefing up certain parts, like the scale or meaning of human sacrifices linked to it. They also tied it closely to their main god Huitzilopochtli and their empire's ideas.6 For Patolli, the consistent liking for the cross-shaped board in Aztec settings, compared to the more varied shapes found earlier and elsewhere, might show a specific Aztec standard or symbolic focus.36

It's clear the Aztecs didn't invent many of their biggest games; they inherited and built upon deep-rooted Mesoamerican traditions. What made them unique was often how they wove these old pastimes into their own empire's ideas, their specific religious views (like Huitzilopochtli's big role in Ōllamaliztli), and their complex social systems. The Aztecs often cranked up the ritual and political importance of these games, changing them to fit the needs and reflect the views of their growing empire.

A Shared Playground: Games Across Mesoamerica

The games the Aztecs played were part of a bigger picture of fun and ritual across all of Mesoamerica.

- Maya: The Classic and Postclassic Maya played a ballgame called Pitz or Pok-ta-Pok. It was very similar to Ōllamaliztli, with a solid rubber ball, players using their hips, I-shaped courts, and strong links to ritual sacrifice.6 One big difference in some Maya courts, like at Chichén Itzá, was that the stone hoops were placed very high, making it incredibly hard to score through them.13 The Maya creation story, the Popol Vuh, which tells of Hero Twins playing the ballgame in the underworld, was key to what the game meant for them.6 The Maya also played a game like Patolli, sometimes called Bul, which was tied to farming cycles and corn rituals.3

- Mixtec and Zapotec: These cultures from Oaxaca also played the Mesoamerican ballgame.6 Patolli was common among them too; Mixtec codices like the Codex Vindobonensis I have clear pictures of Patolli boards and related gods.1 It's interesting that the modern game pelota mixteca, a big cultural thing in Oaxaca today, actually comes from a Spanish handball game brought over during colonial times. It's not a direct survivor of the pre-Columbian hip-ball game, though it ended up filling a similar social role after the native ballgame was stopped.33

- Toltec: The Toltecs, who the Aztecs looked up to as cultural ancestors, also played the ballgame.6 Archaeological finds from their capital, Tula, include Patolli boards.36 Also, some experts think the Volador ceremony might have started with the Toltecs.55

- Inca: The Inca civilization grew in the Andes region of South America, a different cultural area from Mesoamerica.105 While these research notes mention the Inca when comparing video games106 or in general overviews of civilizations105, they don't give details on historical Inca games that would let us make a direct, meaningful comparison with specific Aztec pastimes like Ōllamaliztli and Patolli based on these sources.

The fact that Ōllamaliztli and Patolli (or similar local games) were played by so many different Mesoamerican cultures, like the Maya, Mixtec, Zapotec, Toltec, and Aztec, shows a shared cultural foundation and deep, old historical connections. Even though specific rules, court sizes, and exact symbolic meanings definitely changed from culture to culture or region to region, the basic ideas and ritual links of these games were found all over Mesoamerica. This shared heritage suggests they either came from the same place or there was a lot of cultural sharing and spreading over many centuries, with each culture tweaking these core traditions to fit its own unique society and view of the cosmos.

Change and Survival: Aztec Games After Spanish Arrival

When the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s and colonized Mesoamerica, it had a huge and often terrible effect on native games and fun activities.

- Spanish Suppression: Driven by strong religious beliefs and a desire to get rid of practices they thought were "idolatrous" or pagan, Spanish missionaries and colonial leaders actively stopped many native games.6 Games like Ōllamaliztli, with its clear ties to human sacrifice and non-Christian gods, and Patolli, with its strong connection to gambling and fortune-telling, were especially targeted. Game boards, like Patolli mats, and other related gear were often purposely destroyed.34

- Survival and Hybridization: Despite this crackdown, some native game traditions showed amazing strength, surviving in changed forms or influencing new mixed practices.

- Ōllamaliztli: The ancient ballgame didn't completely vanish. It survived in some remote areas, changing into modern forms like Ulama , which is still played today, especially in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. 1 The ulama de cadera (hip ulama) version is seen as the most direct descendant of the Aztec Ōllamaliztli. 24

- Patolli: This board game was also harshly suppressed because of its gambling and fortune-telling aspects. However, it too survived in various forms and is apparently still played in some communities today under different names. 36 Ironically, some experts think the Spanish presence might have accidentally helped spread Patolli or similar games to other areas, like the American Southwest. 36 The way Nahuatl words were adapted to describe new European games also shows cultural interaction; for example, Fray Alonso de Molina's 16th-century dictionary has terms like amapatolli ("paper-patolli") for European playing cards and quauhpatolli ("wood-patolli") for chess. 36

- Volador Ceremony: This ritual also faced opposition but managed to survive, especially among the Totonac people. Over time, some Catholic elements were mixed into the ceremony, showing a process of blending cultures. 40

- Introduction of Spanish Games: The Spanish also brought their own games, some of which were adopted and adapted by Mesoamerican people. A good example is the Spanish handball game ( pelota a mano ). After it was introduced, it changed in places like Oaxaca into the game now known as pelota mixteca . This game, though European in origin, came to fill a similar social and fun role as the suppressed pre-Columbian ballgame. 33

The Spanish crackdown on major Aztec games, driven by religious intolerance and a wish to tear down native belief systems, caused a major cultural break. This gap was then filled in different ways: native games secretly hung on and changed (like Ulama and regional Patolli versions), or European games were adopted and transformed, fitting into the existing native social scene (like pelota a mano turning into pelota mixteca). This complicated mix of suppression, survival, change, and replacement shows both how strong native cultural practices were and the lively, often unequal, ways cultures interacted and blended during the colonial period in Mesoamerica. The way Nahuatl words were adapted for European games also shows this ongoing cultural conversation and mixing.

Aztec Games: Myths, Misconceptions, and Modern Life

The influence of Aztec games and culture reaches into our modern times, often through popular depictions that aren't always historically accurate. It's important to clear up common misunderstandings and see how these ancient traditions show up in today's media.

Setting the Record Straight: Common Myths About Aztec Games

Several terms and ideas get wrongly linked to Aztec games in popular culture, often with no real historical backing.

- "Aztec Tetris": There's no proof in the historical or archaeological info we have that suggests an ancient Aztec game like Tetris ever existed. 108 The term "Aztec Tetris" mostly shows up today in relation to fabric patterns or designs that have geometric, interlocking shapes similar to the video game Tetris, but with an "Aztec" style label. 110 This is a modern, out-of-time connection based on how things look, not on any real historical Aztec game.

- "Azteca Game" (App/Slot Game): When people say "Azteca Game" nowadays, they usually mean modern entertainment products. For example, "Legend of Azteca" is a 6-reel slot machine game 112 , and "Mexico Soccer Azteca Game Day Jersey" is modern sports clothing. 113 These are commercial items using the Aztec theme for branding and aren't based on any specific historical Aztec game called "Azteca Game."

- "Aztec Highland Games": This term refers to a modern Celtic festival, the "Aztec Highland Games and Celtic Festival," held in the modern city of Aztec, New Mexico, USA. 114 This event celebrates Scottish and Irish heritage with traditional music, dance, and athletic contests typical of Highland Games. 114 Its connection to the historical Aztecs is just in name, based on the modern town's geographical name, and it has nothing to do with actual Aztec games or cultural practices.

The way terms like "Aztec Tetris" pop up, or how the "Aztec" name gets stuck onto completely unrelated modern games or products (like the Highland Games in Aztec, New Mexico), shows something common in pop culture. Historical cultural names often get used out of time or wrongly for branding, or links are made based on shallow similarities or just because names sound alike, usually with no real historical connection or understanding. This really shows why we need to think critically when we see popular portrayals of ancient cultures.

Aztecs in Pixels: How Video Games Portray Ancient Pastimes

Aztec culture, history, and warfare have inspired many modern video games, especially empire-building and strategy games. Titles like Age of Empires, Civilization, Medieval II: Total War, and Theocracy are known for using Aztec themes.116

These games often try to look historically real in their graphics. For instance, Tenochtitlan's buildings or Aztec warrior outfits and weapons (showing differences between commoner macehualtin with cotton armor and slings, and elite Eagle and Jaguar Knights with their special gear and macuahuitl) might show they tried to be accurate based on historical info.116 Some games also have stories or "historical info" parts that use known historical people or events.116 Cultural bits, like god names (Coatlicue, Tezcatlipoca, Cipactli, Cinteotl) or specific Aztec things like "Tlaloc canoes" (though whether this term for war canoes is historically spot-on is questionable), sometimes get mixed into game mechanics, like "Big Button Technologies" for making units or getting special powers.116

But even with these tries to include historical details, how Aztec culture is shown in video games is often simplified and sometimes misrepresented. Game makers often make complex cultural backgrounds simpler, using well-known symbols and clichés to make the game easy to get into or fun for lots of people.116 Older games, especially, have been called out for spreading harmful stereotypes, like showing Native Americans as "savages" or boiling down diverse cultures into one-size-fits-all "Mystic Warrior" types that make light of or misuse native beliefs without enough research or respect.117 Even in newer games, misunderstandings or culturally insensitive depictions can happen. A good example is when the Cree Nation criticized how Chief Poundmaker was shown in the Civilization series, saying it pushed colonial ideas of conquest onto First Nations' ways of seeing the world.117 The fact that not many Native and Indigenous people work in game development studios is often mentioned as a reason for these problems of not being shown enough or being shown wrongly.117