Order on a Slippery Earth: The Structure and Practice of the Aztec Legal System

The Aztec Empire enforced social and cosmic order through a formal legal system. This article examines the structure of this system, from its philosophical foundations in the concept of a "slippery earth" to its hierarchy of local and supreme courts. It covers judicial procedures, the use of evidence, and the specific civil and criminal laws that governed Aztec society, from property rights to capital punishment.

Part I: The Philosophical and Political Foundations of Aztec Law

The Aztec legal system both controlled social behavior and applied the society's core cosmological beliefs. When the Spanish arrived in the early 16th century, they found an established judicial system governing all aspects of Aztec life. 1 The system integrated cosmological and moral philosophy into its practical application. Its purpose was to deter crime, provide restitution, reinforce state authority, and maintain cosmic order. Aztec law combined ancestral tradition, religious beliefs, and imperial decrees.

The Core Philosophical Problem: Maintaining Balance on a "Slippery Earth"

The core of the Aztec worldview was the problem of maintaining balance on the "slippery earth" ( tlalticpac )?. 3 This phrase, found throughout the huehuetlatolli (elders' discourses), captured the Nahua perception of the world as an inherently treacherous and unstable place. 3 The concept reflected both social conduct and their cosmology. The universe was understood to be constituted by a single, sacred energy or force called teotl . 4 This impersonal power permeated all existence, manifesting as a "dialectical polar monism," a cyclical oscillation of complementary opposites like order and disorder, life and death, and light and darkness. 4

Human actions were believed to directly affect this cosmic process. 5 The goal of a proper life was to achieve neltiliztli , a state of "rootedness," by living a balanced, moderate life in harmony with the order of teotl . 3 Any action that created excess or imbalance threatened the individual, society, and the cosmos itself. The legal system was the state's primary instrument for addressing these disruptions and enforcing the moderation required to walk safely upon the slippery earth.

Tlatlacolli: Crime as Cosmic Disruption

This philosophical foundation shaped the Aztec concept of crime. A criminal or immoral act was known as tlatlacolli , a term from a verb meaning "to damage" or "to harm". 6 Unlike the Christian concept of "sin," tlatlacolli was not an offense against a personal God that induced guilt. Instead, it was an act that introduced damage, disorder, and "filth" ( tlazolli ) into the world, disrupting the equilibrium of the social and cosmic realms. 6

An act of tlatlacolli was believed to invite dangerous cosmic forces into one's home and body, potentially leading to illness or misfortune for the offender and their family. 6 Crime was therefore a communal and cosmic matter, not just a personal failing. Consequently, the judicial process aimed to punish the guilty and ritually cleanse the tlazolli created by their actions, thereby restoring social and cosmic balance. This worldview provided ideological justification for the state's authority, positioning its officials as guardians of universal order.

Sources of Law: Tradition, Religion, and Imperial Decree

Aztec law drew authority from several sources. A significant portion was based on custom, which the Mexica adapted from established societies in the Valley of Mexico. 1 These norms governed many aspects of daily life.

Religion was a primary source of legal authority. Laws were seen as essential for maintaining cosmic balance and appeasing deities like the supreme solar and war god Huitzilopochtli. 9 Priests, as interpreters of divine will, played a role in shaping and legitimizing the legal code. 11 Oaths sworn in a god's name, for instance, were a cornerstone of judicial procedure. 13

Finally, imperial decrees issued by the Huey Tlatoani (emperor) were a major source of codified law. The most famous lawgiver was Nezahualcóyotl, the ruler of Texcoco (r. 1429–1472), a city-state known for its cultural and legal systems. 14 Drawing on regional legal traditions, he enacted a code of eighty laws covering issues like treason, robbery, adultery, homicide, and military misconduct. 14 This legal framework was so influential that it was adopted in other parts of the empire and served as a model of governance, creating councils of finance, war, and justice to administer the state. 12

Part II: The Judicial Apparatus: A Hierarchy of Courts and Judges

The Aztec legal system was administered through a multi-tiered judicial system that reinforced the empire's social and political hierarchy. Justice was dispensed through local, high, and specialized courts, each with its own jurisdiction. This structure ensured that the law was both accessible at the local level and centrally controlled by the imperial elite.

The Tiered Court System: From the Neighborhood to the Palace

Local courts formed the base of the judicial system, operating within each calpulli (city district). These courts, held in marketplaces or public plazas, handled minor civil and criminal cases. 2 The judge at this level was typically a respected elder or a veteran warrior, elected by the community. 13 This suggests some local autonomy, as judges were chosen for their wisdom and judgment. These judges were supported by assistants who acted as a local police force, responsible for summoning or arresting suspects. 13

More serious cases were escalated to higher courts in the capital cities of the Triple Alliance: Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. In Tenochtitlan, the high court was the teccalco ; in other capitals, it was the tecalli . 12 These courts were permanently in session and were staffed by professionally trained judges who adjudicated major criminal cases and delivered final sentences in civil disputes. 13 A distinct high court, the tlacxitlan , was designated to hear cases involving the nobility ( pipiltin ) and high-ranking warriors, underscoring the legal segregation of the social classes. 13 This court was staffed by three or four professional judges and was accountable to the supreme court.

The supreme courts held the highest judicial power, and their verdicts were final. 13 In the imperial capital of Tenochtitlan, a Supreme Court of twelve judges convened every twelve days. This body was presided over by either the Cihuacoatl , the emperor's second-in-command, or the Huey Tlatoani himself. 13 The city of Texcoco, with its reputation for legal excellence under Nezahualcóyotl, also hosted a special Court of Appeal. This tribunal, composed of twelve judges and presided over by the king of Texcoco, was held every twelve days to decide the most difficult cases from across the empire. 2

Specialized Jurisdictions

The Aztec system also had specialized courts with autonomous jurisdiction. The merchant's guild, the pochteca , operated its own commercial courts. 2 Staffed with twelve judges, these tribunals could try and execute offenders for crimes related to the marketplace, such as using false measures or selling stolen goods. 12 This legal independence reflected the privileged status of long-distance traders in Aztec society.

Other specialized courts included military tribunals, staffed by four judges, which dealt with matters of military discipline and could be convened immediately after a battle. 13 There were also religious courts for offenses by priests or pertaining to temples, and special tribunals within the emperor's palace to adjudicate crimes by the highest dignitaries. 13 This network of jurisdictions shows that justice was tailored to the social, economic, and political context of the crime and the offender.

The Judges: Qualifications, Training, and Status

The role of a judge was prestigious and carried great responsibility. With the exception of elected local judges, jurists were drawn from the noble class and required the emperor's personal approval. 15 The position required extensive preparation. Aspiring judges trained at the elite calmecac schools, the same institutions that educated future priests and high-ranking officials. 15 This formal education was followed by a practical apprenticeship, where they learned the law and court procedures by observing an active judge. 15

Aztec judges were held to a high ethical standard. They received a state salary, paid from the proceeds of lands set aside for that purpose, to ensure their independence. 13 They were expected to deliver impartial verdicts, regardless of the litigants' social status, and were forbidden from accepting bribes. 13 An accusation of corruption against a judge was a grave matter; if proven, the penalty was death. 2 This self-policing was critical to maintaining the judiciary's legitimacy and public respect for the law. The system aimed to produce judges who were both learned in law and possessed the moral judgment needed to maintain social order.

Table 1: The Aztec Judicial Hierarchy

| Court Name | Jurisdiction | Presiding Officials | Path of Appeal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Court ( Calpulli ) | Minor civil and criminal offenses within a city district. | Elected local elder or veteran warrior. | To Teccalco / Tecalli High Court. |

| Teccalco / Tecalli (High Court) | Serious criminal cases; final judgment in civil disputes. | A president and 2-3 professionally trained judges. | To Supreme Court for criminal cases. |

| Tlacxitlan (Noble's High Court) | Cases involving nobles ( pipiltin ) and high-ranking warriors. | 3-4 professional judges. | To Supreme Court. |

| Commercial Court ( Pochteca ) | Marketplace offenses (fraud, theft); trade disputes. | 12 judges from the merchant guild. | Autonomous; had power of execution. |

| Military Court | Offenses by soldiers (desertion, insubordination). | 4 military judges. | Autonomous; could be held in the field. |

| Texcoco Appellate Court | Most difficult cases from across the empire. | King of Texcoco and 12 judges. | Final judgment. |

| Supreme Royal Court (Tenochtitlan) | Most serious crimes; appeals from lower courts; cases involving high dignitaries. | The Huey Tlatoani or the Cihuacoatl and 12 judges. | Final and absolute judgment. |

Part III: The Legal Process in Practice: From Accusation to Judgment

The journey of a case through the Aztec courts was a systematic process that combined sacred oral tradition with bureaucratic record-keeping. This approach reinforced the legitimacy of judgments by making them appear both divinely sanctioned and factually sound.

Initiating a Case and Courtroom Procedure

A legal proceeding began when one party formally filed charges against another. 13 The accused was then brought before the judge's dais to confront their accuser. 13 The Aztec system had no professional lawyers. An individual could bring a friend to help plead their case, suggesting the system valued personal testimony over specialized arguments. 13 The proceedings were swift and focused on uncovering the truth through direct examination.

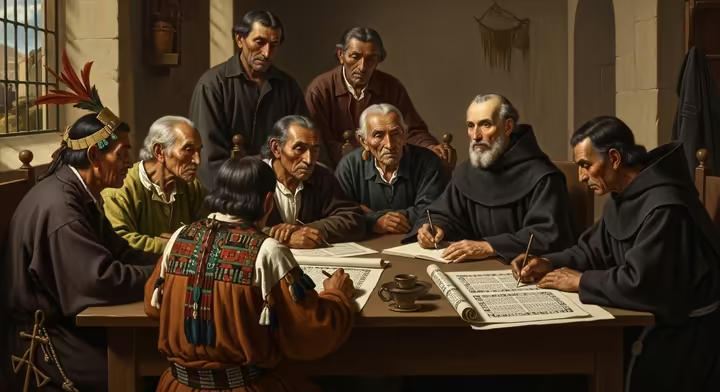

Evidence: The Interplay of Oral Testimony and Pictographic Codices

Evidence in Aztec courts came from sworn oral testimony and official written records. Oral testimony was paramount. All witnesses and litigants swore a sacred oath to tell the truth in the name of Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun. 13 This ritual act, performed by touching the earth and then one's lips, transformed testimony from a simple statement into a sacred vow. 13 The penalty for perjury was the same punishment that the accused would have received, a powerful deterrent against false witness. 12 The judges then used cross-examination to probe the testimony. 13

This oral tradition was complemented by a system of pictorial records. Scribes, known as tlacuilos , were respected artisans, second in importance only to judges. 13 Using pictographs and glyphs, these scribes recorded legal codes, land deeds, tribute lists, genealogies, and court proceedings. 8 These documents (codices) served as formal legal records and mnemonic guides for court evidence. 18 For example, the Codex Mendoza, though produced in the early colonial period, contains detailed lists of tribute obligations, reflecting a pre-existing system of imperial record-keeping. 19 The Codex Osuna, also from the colonial era, was created to present pictorial evidence to Spanish authorities regarding unpaid debts, demonstrating the continuity of using such documents for legal claims. 21 Combining the sacred oath with the state archive created a dual-validation system for evidence. A judgment was considered correct if supported by both witness testimony and state codices, making decisions difficult to challenge.

Appeals and Duration of Proceedings

The Aztec judiciary had a clear hierarchy for appeals. A litigant unsatisfied with a verdict from a local calpulli court could have the case forwarded to a higher tecalli court for review. 13 From there, criminal cases could be appealed to the Supreme Justice Court in Tenochtitlan or the Court of Appeal in Texcoco. 2 The final verdict from these supreme bodies was absolute. 13

The system valued efficiency. According to multiple sources, legal proceedings in the higher courts were subject to a time limit. No case was permitted to last longer than eighty days, the equivalent of four twenty-day months in the Aztec calendar. 2 This deadline prevented endless litigation and ensured swift judgments.

Enforcement and Public Order

Once a final judgment was rendered, it was carried out by law enforcement officials. These officers, likely known as achcacauhtin , were responsible for arresting suspects and carrying out sentences, which ranged from public shaming to execution. 13 Law enforcement was part of a broader administrative structure for maintaining public order. This included officials like the calpixque (tax collectors) and the capullec (neighborhood chiefs), who ensured that tribute was paid and civic duties were performed. 22 Public executions in places like the marketplace served as a visible deterrent. 13

Part IV: The Law of the Land: Criminal and Civil Codes

Aztec law maintained social hierarchy, economic stability, and moral order. The legal codes, particularly the eighty laws attributed to Nezahualcóyotl of Texcoco, covered a wide array of criminal and civil matters, with punishments calibrated to the crime and the offender's status. 14

Criminal Law and Punishment

The Aztec penal code was harsh, partly because the system lacked long-term prisons. 12 Justice relied on corporal punishment, capital punishment, enslavement, and restitution. Major crimes, which damaged social and cosmic order, included homicide, treason, rape, kidnapping, witchcraft, and moving agricultural boundary markers. 12

Punishments for specific offenses reveal Aztec priorities. Petty theft was resolved through restitution. If a thief could not repay the value of the stolen goods, they became the slave of their victim, which compensated the victim. 12 However, theft of certain items was a capital crime. Stealing from a temple or a merchant, taking military insignia, or taking more than twenty ears of corn from a field could all be punished by death. 12 These laws protected religious sites, trade, military honor, and the food supply.

Adultery was another capital offense, typically punished by public stoning or strangulation for both parties. 6 A double standard existed, reflecting the patriarchal nature of Aztec society: a man was only guilty of adultery if he had relations with a married woman, whereas a married woman was deemed guilty regardless of her partner's marital status. 12 The law was primarily concerned with protecting lineage and ensuring the legitimacy of heirs.

Public drunkenness was harshly policed as a source of social chaos. For a commoner, a first offense might result in public humiliation, such as having their head shaved, and the demolition of their home. 12 A second offense could lead to death. For nobles and priests, who were expected to be moral exemplars, a single instance of public intoxication was often a capital crime. 24 Only the elderly, defined as those over 70, were legally permitted to consume the alcoholic beverage pulque as they wished. 12

Economic crimes were also punished severely. In the marketplaces, merchants using false weights or measures faced the death penalty. 12 This strict enforcement was essential for maintaining trust in the empire's commercial network.

Slander or malicious gossip was treated as a major crime that could warrant the death penalty. 12 In a society built on a rigid hierarchy, a person's reputation was a critical asset, and malicious gossip was seen as an assault on the social fabric, capable of inciting public disturbances and undermining authority.

Civil Law and Social Regulation

Aztec civil law regulated family, property, and labor. Marriage was a formal, contractual process, often arranged by a professional matchmaker ( ah atanzah ). 25 While most commoners were monogamous, the law permitted nobles to practice polygyny, which allowed them to forge alliances and accumulate wealth through the labor of multiple households. 26 Divorce was also legally recognized. A couple could petition a court for separation, and if granted, property was often divided equally. Custody of children was typically split by gender, with fathers taking sons and mothers taking daughters. 23

Property and inheritance laws reflected the society's dual structure of communal and private ownership. Most land was held communally by the calpulli and allocated to families for cultivation. This land could not be sold, and if a family died out or left the land untended for more than two years, it reverted to the calpulli for redistribution. 27 The nobility, in contrast, could own private estates, known as pillalli , which were worked by serfs or tenants. 28 Women in Aztec society could inherit, own, and manage their own property independently of their husbands. 27

The legal status of slaves, or tlacotin , is one of the most distinctive aspects of Aztec civil law. Unlike the chattel slavery introduced by Europeans, Aztec slavery was not a hereditary or race-based condition. A person became a tlacotli as a judicial punishment for a crime, as a means of paying off a debt, or by voluntarily selling oneself or a family member into bondage during a famine. 29

This was a contractual status with defined rights and avenues to freedom. Tlacotin were not considered property. They could marry (including to free persons), have children (who were born free), own property, and even own their own slaves. 29 They were legally protected from abuse and could not be resold without their consent, unless declared incorrigible by a court. 30 Several legal pathways to freedom existed. A slave could buy their freedom back, be released by their master, or be replaced by a family member. 30 Furthermore, a slave who escaped from the marketplace and reached the royal palace grounds without being stopped by their master was granted immediate freedom. 30 This system functioned less as an institution of permanent bondage and more as a legal mechanism for penal labor, debt management, and a social safety net.

Part V: Law, Status, and Society

The Aztec legal system maintained its stratified society. The law was not applied universally; it shaped and reflected social status, privilege, and responsibility. It governed everyone, from the emperor to the common farmer.

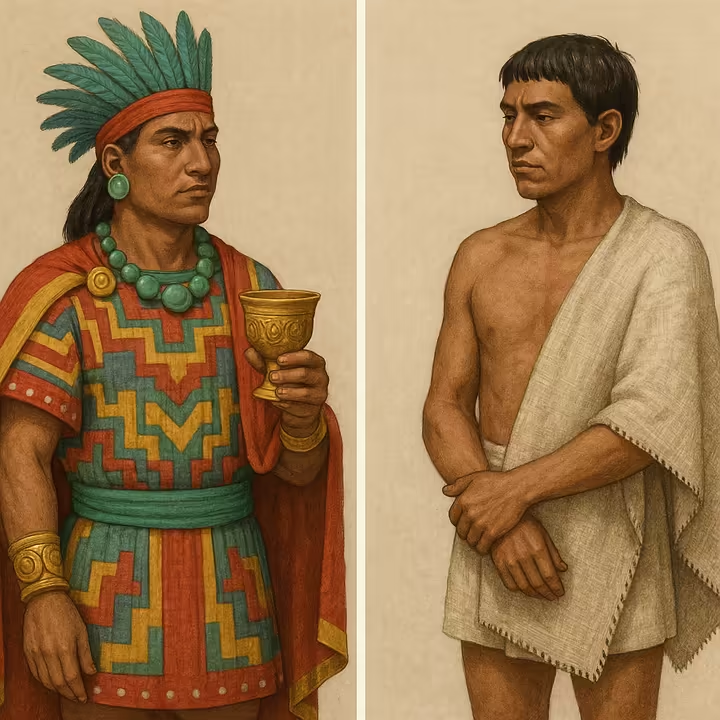

Law as a Reflection of Social Hierarchy

The law was designed to preserve the class system that divided society into nobles ( pipiltin ) and commoners ( macehualtin ). 2 The existence of separate high courts, such as the tlacxitlan for nobles, codified the idea that the elite were to be judged by their peers. 13

The most visible manifestation of this legal stratification was the enforcement of sumptuary laws. These were regulations that governed the display of luxury goods, tying material culture to social status. 32 For example, only nobles were legally permitted to wear cotton garments, adorn themselves with certain precious stones, drink cacao, or carry bouquets of flowers. 28 A commoner who violated these laws was committing a crime. By controlling access to the symbols of power, the law made the social hierarchy visible in daily life.

The Paradox of Harsher Punishments for the Elite

The Aztec legal system imposed harsher penalties on nobles than on commoners for the same offense. 24 This contrasts with many other societies where the elite have legal immunity. In the Aztec world, a noble or priest caught in public drunkenness could be executed for a first offense, whereas a commoner might receive a more lenient punishment like public head-shaving or the destruction of their house. 24 Similarly, crimes committed by nobles were often punished in private to avoid public scandal, but the penalties, which could extend to their families, were severe. 28

This approach was a tool for political legitimization. The rationale was that the nobility, by virtue of their privileged birth and elite education, had a greater moral responsibility to act as examples. 12 Their transgressions were seen as causing greater "damage" ( tlatlacolli ) to the social and cosmic order. By holding the elite to a higher standard, the state linked privilege with responsibility. This created a social contract where commoners accepted noble privileges because the law held them strictly accountable. It reinforced state stability by preventing the perception that the justice system only served the powerful.

The Commoner's Experience with Justice

For the average macehualli , the legal system was a feature of daily life, governing everything from land use to market transactions. 2 Their primary interaction with the judiciary would have been the local calpulli court. Because the local court was accessible, held in public, and presided over by an elected community member, the system was not entirely remote. 13 A commoner could bring a dispute against a neighbor over property or minor theft and receive a hearing.

However, the system's severity meant any transgression could have dire consequences. The constant threat of harsh punishment for offenses like drunkenness or marketplace fraud served as a powerful mechanism of social control through deterrence.

Confession, Shame, and Social Control

Justice was also maintained through public shame and spiritual confession. Public humiliation was a recognized punishment, particularly for first offenses. Having one's head shaved and being paraded through the marketplace was a common penalty designed to use social pressure to correct behavior. 34

A parallel justice system existed in the spiritual realm through confession. The Nahuas believed in a deity named Tlazolteotl, whose name translates to "Filth Deity" but who acted as a purifier, the "eater of filth". 6 A person could, once in their lifetime, confess their tlatlacolli to a priest of Tlazolteotl. The act was a ritual of purification, not absolution in the Christian sense. The confession was believed to transfer the "filth" of the misdeed to the deity, cleansing the individual and restoring their personal balance. 6 This ritual resolved moral transgressions outside the state's punitive system, focusing on spiritual healing instead of corporal punishment. It demonstrates how religious belief was integrated into the Aztec concept of justice.

Conclusion: Gaps in the Historical Record

The Aztec legal system was a developed institution that linked social and cosmic order. It had a judicial hierarchy, a formal legal process combining oral testimony with record-keeping, and a detailed, severe legal code. The system maintained order by reinforcing social hierarchy while holding the elite to high standards. It was both a tool for governance and an instrument for preserving cosmic order.

Our understanding of this system, however, is incomplete. The majority of our primary sources, such as the Florentine Codex compiled by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, the chronicles of Fray Diego Durán, and the pictographic Codex Mendoza commissioned by the Spanish viceroy, were created after the conquest. 36 While these documents preserve information, they are not neutral accounts. They were produced under Spanish supervision, and their content was filtered through a European, Catholic worldview. 17 Indigenous concepts like tlatlacolli were often equated with Christian "sin," and native practices could be misinterpreted or distorted. Distinguishing pre-colonial practices from post-conquest interpretations is a challenge for scholars.

Significant gaps in the historical record remain. Aztec civil law, particularly in areas like contracts and complex inheritance, is not as well documented as criminal law. The specific procedures of the appellate court of Texcoco are mentioned frequently but are not detailed with the same clarity as the courts of Tenochtitlan. While the foundations are clear, many details of legal practice are unknown. Further archaeological and ethnohistorical analysis of Nahuatl documents and Spanish chronicles is needed to clarify the details of the Aztec legal system.

Bibliography

Avalos, F. (1994). The Aztec Legal System . Law Library, Santa Clara University. 39

Berdan, F. F. (2014). Aztec Archaeology and Ethnohistory . Cambridge University Press. 40

Berdan, F. F., & Smith, M. E. (2020). Everyday Life in the Aztec World . Cambridge University Press. 43

Díaz del Castillo, B. (1568). The True History of the Conquest of New Spain . 48

Durán, D. (c. 1581). The History of the Indies of New Spain . 36

Hassig, R. (1988). Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control . University of Oklahoma Press. 51

Hassig, R. (1992). War and Society in Ancient Mesoamerica . University of California Press. 53

León-Portilla, M. (Ed.). (1962). The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico . Beacon Press. 49

Mundy, B. E. (2015). The Death of Aztec Tenochtitlan, the Life of Mexico City . University of Texas Press. 54

Sahagún, B. de. (c. 1577). Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain . 3

Smith, M. E. (2003). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing. 58

Various Authors. Codex Mendoza (c. 1541). 13

Various Authors. Codex Ixtlilxochitl (c. 1600-1650). 21

Various Authors. Codex Osuna (1565). 21

Works cited

- Legal History of Mexico: From the Era of Exploration of the New World to the Present, https://www.harriscountylawlibrary.org/ex-libris-juris/2018/7/24/legal-history-of-mexico-from-the-era-of-exploration-of-the-new-world-to-the-present

- Aztec Social Classes - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/you-contribute/aztec-social-classes

- Aztec moral philosophy didn't expect anyone to be a saint | Aeon ..., https://aeon.co/essays/aztec-moral-philosophy-didnt-expect-anyone-to-be-a-saint

- Aztec Philosophy, https://iep.utm.edu/aztec-philosophy/

- Aztec Philosophy, https://philosophy.williams.edu/files/Aztec-Philosophy-_-Internet-Encyclopedia-of-Philosophy.pdf

- Nahua Moral Philosophy - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/home/nahua-moral-philosophy

- Bedlam in the New World: Madness, Colonialism ... - Harvard DASH, https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/23845437/RAMOS-DISSERTATION-2015.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=16

- The Aztec Legal System - David D. Friedman, http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Academic/Course_Pages/legal_systems_very_different_06/final_papers_04/andrade_aztec_04.html

- The Aztecs, https://embamex.sre.gob.mx/reinounido/images/stories/PDF/Meet_Mexico/7_meetmexico-theaztecs.pdf

- Aztec Religion | World Civilization - Lumen Learning, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldcivilization/chapter/aztec-religion/

- Aztec religion | Practices, Beliefs, & gods | Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aztec-religion

- Crime and Punishment in the Aztec Empire | History Hit, https://www.historyhit.com/crime-and-punishment-in-the-aztec-empire/

- The Aztec legal system - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/you-contribute/aztec-law

- Nezahualcoyotl (tlatoani) - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nezahualcoyotl_(tlatoani)

- www.mexicolore.co.uk, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/you-contribute/aztec-law#:~:text=The%20judges%20would%20usually%20be,judge%20and%20learning%20the%20trade.

- Social structure and daily life in Aztec society | History of Aztec Mexico and New Spain Class Notes | Fiveable, https://library.fiveable.me/deep-histories-of-conquest-aztec-mexico-and-new-spain/unit-3/social-structure-daily-life-aztec-society/study-guide/IjEi0FDOc3Jr06KM

- Aztec Codices - (European History – 1000 to 1500) - Vocab, Definition, Explanations, https://library.fiveable.me/key-terms/europe-1000-1500/aztec-codices

- Aztec Codex - Archaeological Institute of America, https://www.archaeological.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Aztec-Codex.pdf

- The Essential Codex Mendoza, https://www.csus.edu/indiv/o/obriene/art111/readings/The%20Essential%20Codex%20Mendoza.pdf

- Codex Mendoza - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Mendoza

- The Codices: Insight into Aztec Culture - Brewminate: A Bold Blend ..., https://brewminate.com/the-codices-insight-into-aztec-culture/

- Aztec Government — MayaIncaAztec.com, https://www.mayaincaaztec.com/aztec/aztecgovernment

- Aztecs - Hunter-gatherers data sheet (put reference #:page # after each entry) 2pts each quantitative entry, 1 pt for other, https://dice.missouri.edu/assets/docs/utoaztec/Aztecs.pdf

- What Punishment Was like in The Aztec Empire - YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=orvzgyzqlEw

- Aztec society - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_society

- Women and Weaving in Aztec Palaces and Colonial Mexico, https://anth.la.psu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2022/06/Evans_2008ConcubinesandCloth.pdf

- Aztec Society - World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/845/aztec-society/

- Commoners versus nobles - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/aztec-life/aztec-noble-versus-commoner

- Source: Aztec Slaves – Teaching Medieval Slavery and Captivity, https://medievalslavery.org/mesoamerica/source-aztec-slaves/

- How prevalent was slavery in Aztec society? : r/AskHistorians - Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/13gtldf/how_prevalent_was_slavery_in_aztec_society/

- Aztec Empire: social structure and religious practices | Early World Civilizations Class Notes, https://library.fiveable.me/early-world-civilizations/unit-16/aztec-empire-social-structure-religious-practices/study-guide/U0eRBxc0S60Ih7l9

- Were there rich and poor in Aztec times? - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/kids/were-there-rich-and-poor-in-aztec-times

- Basic Aztec facts: AZTEC SOCIAL CLASSES - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/kids/aztec-social-classes

- Which were the most common crimes among the Aztecs? - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/ask-experts/which-were-the-most-common-crimes-among-the-aztecs

- The Goddess of Filth: Tlazolteotl's Role in Aztec Spirituality - Medium, https://medium.com/@riddickdm/the-goddess-of-filth-tlazolteotls-role-in-aztec-spirituality-925198b7f2c6

- Aztecs - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztecs

- Aztec codex - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_codex

- Primary Sources Used in This Project – AHA - American Historical Association, https://www.historians.org/resource/primary-sources-used-in-this-project/

- First Nations Trade, Specialization, and Market Institutions: A, http://thompsonbooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/APR_Vol_7Ch7.pdf

- Aztec Archaeology and Ethnohistory - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287316180_Aztec_archaeology_and_ethnohistory

- Aztec Society and Culture (Part 2) - Aztec Archaeology and Ethnohistory - Cambridge University Press & Assessment, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/aztec-archaeology-and-ethnohistory/aztec-society-and-culture/6B39982030C9DB51C5755AA177A6B121

- Frances Berdan - Fifteen Eighty Four | Cambridge University Press, https://cambridgeblog.org/author-profile/frances-berdan/

- Who Cares about the Lives of Aztec People? | Fifteen Eighty Four | Cambridge University Press, https://cambridgeblog.org/2021/01/who-cares-about-the-lives-of-aztec-people/

- Everyday Life in the Aztec World - ASU Library - Arizona State University, https://lib.asu.edu/shelf-life/everyday-life-aztec-world

- Everyday Life in the Aztec World - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346863384_Everyday_Life_in_the_Aztec_World

- Everyday Life in the Aztec World Berdan, Frances Paperback 9780521736220| eBay, https://www.ebay.com/itm/236001146613

- Everyday Life in the Aztec World - Cambridge University Press, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/everyday-life-in-the-aztec-world/82D95C4132C55797AC9BDB4FE658B9CF

- THE AZTECS AND ARBITRATION - Kluwer Law Online, https://kluwerlawonline.com/api/Product/CitationPDFURL?file=Journals\AMDM\AMDM1952026.pdf

- Foundations: Mesoamerican Civilizations: Aztecs - LibGuides at The Taft School, https://taftschool.libguides.com/c.php?g=1110724&p=8149616

- An Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico (1528) Source #2: Cortés on Meeting Moctezuma (1520), https://ca01000875.schoolwires.net/cms/lib/CA01000875/Centricity/Domain/545/Mexico%20DBQ%20Docs.pdf

- Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control - Ross Hassig - Google Books, https://books.google.com/books/about/Aztec_Warfare.html?id=wk-kOMKnKKEC

- Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control - Ross Hassig - Google Books, https://books.google.com/books/about/Aztec_Warfare.html?id=7M1o9g8MARgC

- (PDF) Mexico and the Spanish Conquest - by Ross Hassig - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250941032_Mexico_and_the_Spanish_Conquest_-_by_Ross_Hassig

- Codex Ixtlilxochitl, Nezahualcoyotl - VistasGallery, https://vistasgallery.ace.fordham.edu/items/show/1688

- Judgement and Punishment in the Aztec empire, from the 'Florentine Codex' by Bernardino de Sahagun, c.1540-85 - MeisterDrucke, https://www.meisterdrucke.us/fine-art-prints/Spanish-School/78846/Judgement-and-Punishment-in-the-Aztec-empire,-from-the-'Florentine-Codex'-by-Bernardino-de-Sahagun,-c.1540-85.html

- Digital Florentine Codex, https://florentinecodex.getty.edu/

- Bernardino de Sahagún and Indigenous collaborators, Florentine Codex - Smarthistory, https://smarthistory.org/bernardino-de-sahagun-and-collaborators-florentine-codex/

- Nezahualcóyotl | EBSCO Research Starters, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/nezahualcoyotl

- "Codex Mendoza, Folio 46 recto (p. 99)" by Christopher Pool and Barry Kidder, https://uknowledge.uky.edu/world_mexico_codices/11/

- Codex Mendoza - Ziereis Facsimiles, https://www.facsimiles.com/facsimiles/codex-mendoza

- Codex Mendoza and Mexican History | Curationist, https://www.curationist.org/editorial-features/article/codex-mendoza-and-mexican-history

- Basic Aztec facts: AZTEC PUNISHMENTS - Mexicolore, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/kids/aztec-punishments

- 25.2: The Aztecs - Humanities LibreTexts, https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Art/Art_History_(Boundless)/25%3A_The_Americas_After_1300_CE/25.02%3A_The_Aztecs