Teotihuacan vs Tenochtitlan: A Tale of Two Mesoamerican Giants and Their Enduring Connection

Two Mesoamerican Giants: An Introduction

Two of Mesoamerica's most awe-inspiring urban centers: the ancient, mysterious city of Teotihuacan, and the later Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan. These cities, though they blossomed centuries apart, both left an indelible mark on the cultural story of ancient Mexico. Their tales aren't just about ancient stones; they're about human ingenuity, how societies evolve, and the powerful way history and myth can shape who we are.

Why compare these two, especially when trying to understand the Aztecs? Well, it turns out Teotihuacan was hugely important to the Aztec worldview, and therefore, to how we understand Aztec civilization today.

Picture this: Teotihuacan was already an ancient, revered ruin when the people we know as the Aztecs, specifically the Mexica, began to rise to power in the Valley of Mexico.1 The Aztecs didn't just glance at these ruins from afar. They actively engaged with them, weaving the legacy of this older civilization into the very fabric of their own culture, religion, and identity.

This wasn't a passive inheritance; it was a dynamic process of making sense of and adopting what they found. It was the Aztecs who gave the abandoned city its Nahuatl name, "Teotihuacan," often translated as "the place where the gods were created" or "birthplace of the gods."1

Just by naming it, they were claiming a piece of its meaning and fitting it into their own understanding of the cosmos. What's more, they wove Teotihuacan into their most fundamental creation myths, pinpointing it as the sacred spot where our current world, the Fifth Sun, was born through the gods' self-sacrifice.6

We even have historical accounts and archaeological clues suggesting that Aztec rulers, like Montezuma, made pilgrimages to Teotihuacan to pay their respects to the site and its deified ancestors.1 This active veneration tells us that the Aztecs strategically used Teotihuacan's legacy, perhaps to legitimize their own rule, to ground their beliefs in a deeper, more ancient past, and to connect themselves to a lineage of perceived greatness.

The mystery surrounding Teotihuacan, who built it? what was its original name?, paradoxically made it even more powerful symbolically, allowing the Aztecs to write their own meanings onto its monumental landscape.

In this report, we'll dive into what made each city unique, their rise to prominence, how their societies were structured, their urban planning, and their religious beliefs. Most importantly, we'll shed light on the profound and complex relationship between them, especially how the Aztecs saw and interacted with the legacy of Teotihuacan. Getting to know these two metropolises is key to grasping the depth and continuity of Mesoamerican civilization, and particularly for appreciating the rich cultural tapestry the Aztecs inherited and rewove.

Teotihuacan: The Mysterious 'Birthplace of the Gods'

A Glimpse into Teotihuacan's Past

Teotihuacan's story unfolds over many centuries, marking it as one of the most significant urban achievements in the pre-Columbian Americas. The first signs of settlement in the Teotihuacan Valley appear as early as 400 BCE, with small farming communities laying the groundwork for what would become a colossal city.1 Some scholars place these initial settlements a bit later, between 150 BCE and 100 CE.16 A major period of urban growth kicked off around 100 CE.4 This boom might have been partly fueled by people fleeing Cuicuilco, a rival center in the Valley of Mexico that was devastated by a volcanic eruption, possibly from the Xitle volcano.1

The city truly hit its stride during Mesoamerica's Classic Period, generally dated from around 100 CE to 650 CE.5 In its early days of monumental building, iconic structures like the Pyramid of the Sun (around 100 CE), the Pyramid of the Moon (around 150 CE), and the Temple of Quetzalcoatl (also known as the Feathered Serpent Pyramid, finished around 200 CE) rose to dominate the landscape.4 Between 300 CE and 550 CE, Teotihuacan reached its peak, wielding considerable influence over much of Mesoamerica.16 At its height, estimated around 400-500 CE, the city's population swelled to somewhere between 80,000 and 200,000 inhabitants, making it one of the largest urban centers in the entire world at that time.1

However, this golden age wasn't destined to last. Around 550-600 CE, a catastrophic event, or perhaps a series of them, led to the deliberate burning and sacking of the city's major monuments and elite buildings.1 After this destruction, Teotihuacan went into a sharp decline and was largely abandoned by the 7th or 8th century CE.1

One of Teotihuacan's most enduring mysteries is who actually built it and what language they spoke.1 Despite tons of archaeological work, we still don't have a definitive answer. Theories have linked its origins to various Mesoamerican cultures, including the Maya, Mixtec, or Zapotec, or to later ethnic groups known from the region like the Nahua, Otomi, or Totonac.1 For many years, people thought the Toltecs, a later civilization, were responsible for Teotihuacan, but that's unlikely from a timeline perspective, as the Toltec civilization flourished centuries after Teotihuacan's decline.1 The idea that people from Cuicuilco migrated there after the volcanic eruption is another hypothesis for the city's early growth and diverse cultural influences.1

This persistent ambiguity about Teotihuacan's founders and their language isn't just an academic puzzle; it's a fundamental characteristic that profoundly shaped how later cultures, especially the Aztecs, saw the city, and it continues to be a major focus for archaeologists. Many scholarly sources emphasize these "known unknowns."1

This very void in a clear historical narrative allowed later peoples, most notably the Aztecs, to project their own cosmological beliefs and origin stories onto the awe-inspiring ruins. By naming the site "Teotihuacan" and weaving it into their creation myths as the place where the gods brought forth the current era,1 the Aztecs filled the historical silence with their own sacred meaning.

The absence of a clear dynastic record, identifiable royal tombs (unlike many Maya sites), or a deciphered written language further deepens the enigma and has led scholars to speculate about different kinds of governance, possibly collective or council-based systems.9

This "blank slate" quality turned Teotihuacan into a potent symbolic resource for the Aztecs. It enabled them to claim a spiritual and ancestral connection to an ancient, divinely touched place without being tied to the specific historical narratives or dynastic claims of its original inhabitants.

It's a fascinating example of how ambiguity itself can become a source of cultural power and a catalyst for reinterpretation by later civilizations.

A Tour of Teotihuacan's Urban Landscape and Architecture

Teotihuacan's ceremonial heart is truly something to behold, defined by its massive, awe-inspiring structures, all meticulously arranged within a grand urban plan.

The Monumental Core:

The city's most iconic features are its pyramids and the central avenue that ties them all together.

-

Pyramid of the Sun:

This is Teotihuacan's largest monument, a colossal structure built around 100 CE.16 It's enormous, measuring about 220 by 230 meters (720 by 760 feet) at its base and rising to a height of roughly 66 meters (216 feet).1 A really significant feature is the natural cave system discovered beneath it, which includes a tunnel ending in a cloverleaf-shaped set of chambers.22 This cave might have been seen as a chicomoztoc, or "place of emergence", a sacred womb from which the first humans or ancestors came into the world, a common theme in Mesoamerican beliefs.27 Recent archaeological digs have uncovered offerings within and beneath the pyramid, further highlighting its ritual importance.28

Sacred Caves and Origins: The cave system beneath the Pyramid of the Sun may have been seen as a chicomoztoc, a mythical 'place of emergence' or ancestral womb, common in Mesoamerican origin stories.

- Pyramid of the Moon: Located at the northern end of the Avenue of the Dead, the Pyramid of the Moon is the second-largest structure at Teotihuacan, built around 150 CE.16 Its shape deliberately echoes the form of the nearby mountain, Cerro Gordo, beautifully integrating the monumental architecture with the natural landscape.19 Extensive excavations have shown that the pyramid was built in several successive stages. Each new phase was often marked by dedicatory burials containing rich offerings of greenstone, obsidian, and shell, as well as the remains of sacrificed humans and animals like eagles, pumas, and serpents.20

-

Avenue of the Dead (Miccaotli):

This grand ceremonial causeway, named Miccaotli by the later Aztecs (who believed the mounds flanking it were tombs), is the central spine of Teotihuacan.15 It stretches for about 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) and is roughly 130 feet (40 meters) wide.15 The avenue is precisely oriented 15.5 degrees east of true north and is lined with numerous smaller temples, palaces, and high-status residential compounds.15

Avenue of the Dead: An Aztec Perspective: The Aztecs named this central causeway Miccaotli ('Road of the Dead'), believing the mounds flanking it were tombs of ancient kings or gods, further cementing its sacred, ancestral significance in their eyes

-

Temple of the Feathered Serpent (Quetzalcoatl) and the Ciudadela:

Within the Ciudadela ("Citadel"), a massive sunken square plaza at the southern part of the ceremonial center, stands the Temple of the Feathered Serpent.15 Completed around 200 CE,16 this six-tiered pyramid is famous for its elaborate sculptures.

Its facades are adorned with hundreds of projecting stone heads depicting the Feathered Serpent (an early version of the deity later known to the Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl) and another goggle-eyed, reptilian entity, possibly a War Serpent or an early form of Tlaloc.1

Associated with the temple's construction are significant sacrificial burials, mainly of warriors with their hands tied, interred with rich grave goods. This indicates the temple's profound ritual and perhaps militaristic significance.1

A remarkable discovery here was a tunnel beneath this pyramid, which yielded an extraordinary array of offerings, including carved wooden objects, rubber balls, pyrite mirrors, and jade statues, all laid out to represent a symbolic underworld.29

The Ciudadela itself is a vast enclosure that could have held a huge number of people, possibly the city's entire adult population, for major public ceremonies.36

Urban Planning:

Teotihuacan is celebrated for its highly organized and geometrically precise urban grid, a feature unique in its scale and complexity among Mesoamerican cities.1

- The city's layout is orthogonal, meaning streets and buildings are aligned to a primary axis 15.5 degrees east of astronomical north.20 This specific orientation is thought to reflect alignments with significant celestial bodies, like the sun and the planet Venus, on important dates within the Mesoamerican ritual and agricultural calendars.20 The San Juan River, which flows through the valley, was even canalized and diverted to fit this predetermined grid.8

-

Apartment Compounds:

A defining feature of Teotihuacan's residential architecture is the apartment compound.3 Archaeologists estimate that between 2,000 and 2,300 of these single-story, multi-family structures housed about 85% of the city's inhabitants.20 Typically measuring around 60 by 60 meters (200 by 200 feet), these compounds consisted of dozens of interconnected rooms, patios, and small shrines arranged around open-air courtyards, all enclosed by a thick exterior wall.20 This architectural form suggests a high degree of social organization and provided a unique level of housing stability for the average resident. Who lived in these compounds? It might have been based on kinship ties (perhaps patrilocal, where families lived with the husband's kin) and craft specialization, with artisans of a particular trade living and working together.15

Urban Innovation: Teotihuacan's Apartment Compounds: Unique for their time, these multi-family, single-story compounds housed ~85% of Teotihuacan's population, suggesting advanced social organization, possibly based on kinship and shared crafts.

Distinctive Architectural Style: Talud-Tablero:

A hallmark of Teotihuacan's monumental architecture is the talud-tablero style.6 This consists of an inward-sloping wall (the talud) topped by a vertical, often framed, rectangular panel (the tablero). This motif is repeated on the tiers of pyramids and platforms throughout the city. While Teotihuacan standardized and popularized this architectural feature, its appearance at other Mesoamerican sites is a strong sign of Teotihuacano influence or contact, earlier examples of talud-tablero are known from the Tlaxcala-Puebla region, predating Teotihuacan's rise.42

The urbanism of Teotihuacan wasn't just a functional arrangement of buildings; it was a powerful statement of ideology and a sophisticated tool for social organization and control. The city's rigid grid system, its precise astronomical alignments, and the sheer monumentality of its ceremonial core all point to a strong central authority capable of conceiving and executing a master plan, as well as mobilizing and managing vast labor resources.9

This highly structured urbanism is quite different from the more organic, less rigidly planned growth patterns seen in many other ancient cities worldwide. The unique apartment compounds, which housed most of the city's population in standardized, collectivized units, suggest a distinctive form of social organization.

This living arrangement might have been designed to foster communal identity, facilitate specialized craft production under state oversight, or exert a degree of social control over a large and diverse populace.15 Such collectivized housing is relatively rare in pre-industrial urban contexts.5

Furthermore, access to the main ceremonial areas, including the tops of the great pyramids, was likely restricted, reinforcing social hierarchies and the special status of priests and elites.20 The Avenue of the Dead, flanked by temples and palaces, served as a grand stage for public rituals and processions, which would have reinforced state power and religious doctrines among the people.

The remarkable feat of diverting the San Juan River to align with the city's grid8 further illustrates a profound assertion of human design over the natural landscape, underscoring Teotihuacan's ordered, cosmologically informed vision.

This comprehensive and ideologically charged urban design likely played a crucial role in integrating a large, potentially multiethnic population15 and projecting the power and worldview of Teotihuacan across Mesoamerica.

Society and Culture in Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan was a complex, highly stratified society, notable for its cosmopolitan character and unique cultural expressions. It was a real melting pot!

Societal Structure:

The city's social fabric was diverse and layered.

-

A Multiethnic Metropolis:

Archaeological and isotopic evidence strongly suggests that Teotihuacan was a multiethnic city, attracting migrants from various regions of Mesoamerica, including Zapotec peoples from Oaxaca, Maya from the lowlands, and populations from the Gulf Coast.1 These groups sometimes lived in distinct ethnic enclaves or neighborhoods within the city, maintaining some of their original cultural practices.15 Research by archaeologist Linda Manzanilla has particularly shed light on these multiethnic neighborhoods, suggesting they had their own internal organization and leadership, often referred to as "intermediate elites" who managed neighborhood affairs and trade.23

A Cosmopolitan Hub: Teotihuacan was a true melting pot, with evidence of distinct ethnic neighborhoods for Zapotec, Maya, and Gulf Coast peoples, each maintaining some cultural practices under 'intermediate elites'.

-

Social Hierarchy:

Society in Teotihuacan was clearly stratified. Elites, who likely included priests, administrators, and perhaps warrior leaders, had privileged access to the city's ceremonial core and were responsible for commissioning monumental architecture and orchestrating large-scale rituals.20

Evidence from burial offerings, the quality of residential architecture, and the distribution of luxury goods within apartment compounds indicates significant variations in wealth and social status among the city's inhabitants.1

The precise nature of Teotihuacan's governance is still up for debate. While some early theories suggested priest-rulers,15 the general lack of prominent royal tombs comparable to those found in Maya sites, and the absence of individualized ruler portraits in public art, have led many scholars to suggest a more collective or corporate form of government, rather than a dynastic monarchy focused on a single ruler.4

- Daily Life: The majority of Teotihuacan's population lived in those apartment compounds we mentioned.15 Daily activities revolved around farming in the surrounding fertile lands, a wide array of craft production (including obsidian tools, ceramics, textiles, and stonework), and participation in local and long-distance trade networks.1 The Teotihuacano diet was based on Mesoamerican staples such as maize (corn), beans, squash, chili peppers, and amaranth, supplemented by hunted game like deer and rabbits, and possibly domesticated animals such as turkeys and dogs.1

Language:

What language, or languages, did the Teotihuacanos speak? We still don't know for sure.1 Given the city's clear multiethnic makeup, it's highly probable that it was a multilingual environment. There is some evidence for a system of writing, perhaps pictographic or glyphic, used mainly for recording dates, names, or ritual information, but it seems to have been more rudimentary and less widespread than the complex hieroglyphic script developed by their contemporaries, the Maya.[15 (citing FAMSF), 13]

Artistic Expressions:

Teotihuacan art is renowned for its highly stylized, often geometric, and symbolically rich aesthetic, which is quite distinct within Mesoamerica.1

- Murals: Many of Teotihuacan's buildings, especially the interior walls of apartment compounds and temples, were adorned with vividly painted murals, created using a fresco-like technique.1 These murals depicted a range of subjects, including deities, elaborately costumed priests or ritual performers, warriors, various animals (jaguars, coyotes, eagles, serpents), and complex abstract or symbolic motifs. One of the most famous examples is the "Great Goddess" or "Mountain-Tree" mural found in the Tepantitla compound. It shows a central female figure from whose head a flowering tree emerges, surrounded by attendants and symbols of fertility and abundance.[15 (citing Smarthistory)]

- Ceramics: Teotihuacan produced a variety of distinctive pottery styles. Among the most notable is "Thin Orange" ware, a finely made, orange-colored ceramic that was widely traded as a luxury good across Mesoamerica.1 Other characteristic ceramic forms include mold-pressed figurines, often depicting humans or deities with standardized attributes, and elaborate, composite incense burners (incensarios), which were typically adorned with intricate appliqued symbols and figures.1

-

Stone Masks and Sculpture:

Highly polished stone masks are among the most iconic artifacts from Teotihuacan.1 These were typically crafted from valued materials like greenstone (serpentine, jadeite), basalt, or andesite, and often featured inlaid eyes made of shell or obsidian. Their exact function is debated, but they may have adorned statues of deities or been attached to funerary bundles of deceased elites. Teotihuacan stone sculpture, in general, tended to be geometric and represented deities, symbolic animals, or generic human forms rather than individualized portraits of rulers.13 Greenstones were particularly prized, likely because their color resembled water and vegetation, linking them to agricultural fertility and life.20

In a large, multiethnic city like Teotihuacan, where a common spoken language might not have been universally understood and where governance may have been more collective than dynastic, the highly standardized and symbolically charged art likely served as a crucial medium for communication and social cohesion.

The widespread presence of murals in both elite ceremonial spaces and commoner residential compounds suggests that art was a public and pervasive way to convey shared ideologies, religious beliefs, and the power of the state.20

The repetitive and stylized nature of key motifs, like the goggle-eyed Storm God, the Feathered Serpent, the Great Goddess, and specific animal imagery, across various media like murals, ceramics, and stone sculpture would have created a recognizable visual language. This visual lexicon reinforced core cosmological concepts and religious doctrines throughout the diverse urban population.1

The general absence of individualized portraits of rulers in Teotihuacan's public art, with figures often depicted generically or as deity impersonators,13 aligns with theories of a more corporate or collective leadership structure, where the overarching ideology, rather than the glorification of a specific dynasty, was paramount.

The state's control over the production and long-distance trade of distinctive, high-quality artistic goods, such as Thin Orange pottery and finely crafted obsidian tools,1 not only fueled the city's economy but also served to project Teotihuacan's cultural influence and prestige far beyond its immediate borders.

Furthermore, the strategic adoption and promotion of certain deities, like the Old Fire God, which had pre-existing roots in other Mesoamerican regions from which migrants likely originated, may have been a deliberate policy by Teotihuacan's leaders to help unify the city's diverse populations under a shared, albeit Teotihuacano-modified, religious umbrella.[15 (citing FAMSF)]

Thus, art in Teotihuacan wasn't just decorative; it was a fundamental tool for building identity, propagating ideology, and asserting power in a complex urban environment.

Teotihuacan's Spiritual World: Beliefs and Practices

Teotihuacan society was deeply religious, with a polytheistic belief system that permeated every aspect of life, from grand state ceremonies to daily household rituals.1

The Pantheon of Gods:

The Teotihuacano pantheon included a range of deities, many of whom had agricultural and elemental associations, reflecting the concerns of a society dependent on the productivity of an often arid environment.

-

The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan:

This female deity seems to have been a primary figure, possibly a creator goddess or a powerful earth and fertility deity.1 She is often depicted in murals and sculptures wearing a fanged mask that can look like a spider's mouth, or as the central figure in the Tepantitla "Paradise" mural, from whose head a flowering, life-giving tree emerges, surrounded by butterflies, spiders, and human figures making offerings.[15 (citing Smarthistory)]

The Enigmatic Great Goddess: A primary Teotihuacan deity, the 'Great Goddess' is often depicted with a fanged mask or as a life-giving tree figure (Tepantitla mural), symbolizing fertility and earthly power. Her exact identity remains debated.

- Storm God (often equated with the later Aztec Tlaloc): A crucial deity characterized by distinctive goggle-like eyes, protruding fangs, and often depicted wielding lightning bolts or associated with water symbols.[1 (citing FAMSF), 1] Given Teotihuacan's location in a relatively dry region, this deity responsible for rain and storms was vital for agricultural success.

- Feathered Serpent (an antecedent to the Aztec Quetzalcoatl): This powerful deity is prominently featured in the elaborate sculptural program of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent in the Ciudadela.1 The Feathered Serpent was associated with water, fertility, creation, and possibly with concepts of rulership and political authority.

- Old Fire God (Huehueteotl): An ancient deity in Mesoamerica, often depicted as an elderly, wrinkled man, typically shown seated and bearing a brazier on his head for burning incense or offerings.[4 (citing FAMSF), 1] His worship may have played a role in unifying Teotihuacan's diverse population, as similar fire deities were known in other regions from which migrants came.

- Xipe Totec: A god associated with spring, agricultural renewal, and the shedding of skins (symbolizing the renewal of vegetation).1

- Chalchiuhtlicue (Water Goddess): While the Great Goddess had strong aquatic connections, a distinct Water Goddess, identified by the Aztecs as Chalchiuhtlicue, is also recognized, notably represented by an impressive large stone statue found at Teotihuacan.[13 (citing World History)]

Rituals and Ceremonies:

Religious life at Teotihuacan was marked by complex and often large-scale rituals. Evidence for these comes from architectural settings, iconography, and extensive archaeological discoveries.

- Human and Animal Sacrifice: There's abundant and clear archaeological evidence that human and animal sacrifice was a central part of Teotihuacano religious ritual. This was particularly true in the context of dedicating major monumental structures like the Pyramids of the Moon and Sun, and especially the Temple of the Feathered Serpent.1 Sacrificial victims often included warriors (some with hands bound), individuals of apparent high status, and non-locals, suggesting that captives taken in warfare may have been among those sacrificed.1 Animals commonly sacrificed included eagles, jaguars, pumas, wolves or coyotes, and serpents, all creatures with potent symbolic meaning in Mesoamerican cosmology.

- Offerings: Dedicatory caches and burial offerings were rich and varied. They contained precious materials such as jadeite and other greenstones, obsidian (blades, figurines, eccentrics), shell artifacts (from both Pacific and Gulf coasts), pyrite (often in the form of mirrors), ceramics, and animal remains.20 These offerings were meticulously arranged and deposited in association with monuments and important ritual events.

- Astronomical Alignments and Calendrics: The precise orientation of Teotihuacan's urban grid and its major ceremonial structures (15.5 degrees east of true north) strongly suggests that religious rituals were timed and aligned with significant calendrical dates and astronomical events, such as solstices, equinoxes, and the movements of celestial bodies like the Pleiades or Venus.13

- Cave and Tunnel Rituals: Natural caves and man-made tunnels held profound sacred meaning. The cave system located directly beneath the Pyramid of the Sun was the scene of ancient fire and water rituals and may have been considered a foundational place of origin or emergence for the Teotihuacano people or their gods.22 Similarly, the long tunnel discovered beneath the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, ending in chambers that may represent a symbolic underworld, was filled with tens of thousands of offerings. This indicates its role as a major ritual space for reenacting creation narratives or communing with supernatural forces.[15 (citing FAMSF)]

Teotihuacan's religious system was far more than just a set of abstract beliefs; it was deeply interwoven with the very fabric of state power, urban design, and economic life. It served as a fundamental mechanism for social cohesion, the legitimization of authority, and the city's perceived interaction with the cosmos.

The monumental pyramids, for instance, weren't merely temples but grand stages for state-sponsored rituals, including large-scale human sacrifice. These dramatic public ceremonies likely served to demonstrate and consolidate the power and control of the elite, while also being seen as necessary for maintaining cosmic balance and ensuring the city's prosperity.9

The careful alignment of the city and its major architectural features with celestial events13 indicates a worldview where the meticulously planned urban order was intended to mirror and harmonize with the cosmic order, with the city's rulers and priests acting as crucial mediators between the human and divine realms.

The prominent worship of deities associated with essential natural resources like water (embodied by the Storm God, the Water Goddess, and aspects of the Feathered Serpent) and agricultural fertility (linked to Xipe Totec and the Great Goddess) underscores the critical role of religion in trying to secure the city's sustenance, especially given its location in a challenging semi-arid environment.1

The presence of foreign materials and possibly foreign individuals among sacrificial victims in ritual contexts30 suggests that religious rituals also played a significant role in Teotihuacan's interactions with other Mesoamerican polities, perhaps as a means of asserting dominance, forming alliances, or ritually incorporating foreign elements and power.

Finally, the discovery of elaborate tunnels beneath the pyramids, interpreted as symbolic underworlds or sacred places of creation,22 points to a profound cosmological foundation for the city's sacred geography and the authority of its leaders, who likely derived legitimacy from their ability to access and mediate with these powerful, chthonic realms.

Teotihuacan: An Economic Powerhouse

Teotihuacan wasn't just a major religious and cultural hub; it was also a dominant economic force in Mesoamerica during its heyday.

Trade Networks:

The city commanded extensive trade networks that stretched across vast distances, connecting it with diverse regions including the Maya lands to the southeast, Zapotec centers in Oaxaca to the south, and various cultures along the Gulf Coast and in western Mexico.1 Evidence for these connections comes from the presence of Teotihuacan-style artifacts at distant sites and, conversely, foreign goods found within Teotihuacan.

Key Commodities:

Several key commodities formed the backbone of Teotihuacan's economic power:

-

Obsidian:

Control over major obsidian sources, particularly the rich deposits at Pachuca (known for its distinctive green obsidian) and Otumba, was a cornerstone of Teotihuacan's economy.1 Obsidian, a volcanic glass, was the primary material for producing sharp cutting tools, projectile points (spear and dart heads), and ritual objects throughout Mesoamerica before metallurgy became widespread. Teotihuacan exported vast quantities of finished obsidian tools and likely also raw obsidian, effectively holding a near monopoly on this vital resource for centuries.19

Obsidian: The Engine of an Economy: Control over Pachuca's green obsidian was key to Teotihuacan's economic might. This volcanic glass, essential for tools and weapons, was traded extensively, making Teotihuacan a dominant economic force.

- Ceramics: Distinctive and high-quality pottery, most notably the "Thin Orange" ware, was produced and widely exported by Teotihuacan, serving as another key trade item and a marker of its cultural influence.1

- Other Goods: While direct evidence is sometimes scarcer, it's likely that Teotihuacan also traded in a variety of other goods, including agricultural products, cotton textiles, cacao (a valuable commodity from lowland regions), exotic bird feathers (like quetzal plumes), marine shells, and other luxury items obtained through its extensive networks.1

Craft Production:

The city was a major center for craft production. Archaeological evidence indicates the presence of numerous workshops dedicated to the manufacture of obsidian tools, ceramics, textiles, lapidary work (stone carving and jewelry), and other crafts.1 This specialized production was likely organized within the apartment compounds, where artisans lived and worked. The Great Compound, a large enclosure near the Ciudadela, has been hypothesized to have functioned as a centralized marketplace, facilitating the exchange of both local and imported goods.26

Teotihuacan's control over critical obsidian sources, especially the high-quality green obsidian from Pachuca, appears to have been a primary engine driving its economic dominance and imperial reach. In a Mesoamerican world where metal tools weren't prevalent, obsidian was the essential material for a wide range of utilitarian and military implements, from knives and scrapers to spear and dart points.3

By monopolizing or heavily controlling access to major obsidian deposits,1 Teotihuacan held a significant strategic and economic advantage over other polities. The widespread distribution of Teotihuacan obsidian artifacts found at archaeological sites across Mesoamerica, from northern Mexico to the Maya lowlands and beyond, attests to the vast scale and reach of its trade networks.1

The considerable wealth generated from this extensive trade in obsidian and other goods, such as fine ceramics, likely financed the construction of the city's massive monumental architecture. It also supported its large and diverse non-agricultural population, including artisans, priests, administrators, and elites, and fueled its military and political influence throughout the region.1

The sophisticated organization of craft production, possibly taking place within specialized apartment compounds where artisans of a particular trade congregated,15 suggests a highly developed economic system that was intricately integrated with the city's unique social structure.

This formidable economic power, fundamentally rooted in resource control and efficient production and distribution systems, was a key factor in Teotihuacan's emergence and long-standing status as a "primate city", the dominant urban center, of Classic period Mesoamerica.4

The Fall of a Giant: Teotihuacan's Collapse and Abandonment

Around 550-600 CE, Teotihuacan experienced a dramatic and violent end to its period of dominance. The city's central ceremonial structures, including major temples and elite residences along the Avenue of the Dead, were systematically burned and, in some cases, ritually desecrated.1 Following this destruction, the city entered a period of rapid population decline, and by 650-750 CE, it was largely abandoned as a major urban center, though some smaller-scale occupation continued in and around the ruins.2

Why Did It Fall? Theories for Collapse:

The precise causes of Teotihuacan's collapse are still debated among scholars, and it's widely believed that a combination of factors, rather than a single event, led to its downfall. Several prominent theories have been proposed:

- Internal Revolt/Social Unrest: Significant evidence points towards an internal uprising. The deliberate and selective burning of elite and religious structures, while many commoner residential areas remained untouched, suggests a targeted attack on the symbols of power and authority.1 This could have been a rebellion by the city's commoners or factions within the elite, possibly fueled by increasing social stratification, resource strain, or dissatisfaction with the ruling regime.4 The fact that only areas of ritual and elite importance were systematically destroyed is a key piece of evidence supporting this theory.60

- External Invasion/Warfare: Another possibility is that Teotihuacan was attacked and sacked by rival groups or outside invaders who exploited a period of internal weakness.1 While Teotihuacan clearly possessed a strong military capacity and exerted influence over other regions, the city itself notably lacked extensive defensive fortifications, which might have made it vulnerable to a concerted attack.1

- Environmental Factors: Prolonged and severe drought, leading to agricultural failure and famine, has been proposed as a significant contributing factor.2 Paleoenvironmental studies have indicated periods of dry conditions in the Basin of Mexico that coincide with Teotihuacan's decline.60 Such environmental stress would have undermined the city's agricultural base, potentially leading to widespread hardship and eroding the authority of rulers who were expected to ensure prosperity through ritual and governance. Resource depletion, such as deforestation for fuel and construction materials, and soil erosion from intensive agriculture, could also have played a role.

- Economic Decline: The disruption of Teotihuacan's extensive trade routes, the loss of control over key resources like obsidian, or the rise of competing economic centers in other parts of Mesoamerica could have severely weakened the city's economic foundations.2 A decline in economic power would have impacted the state's ability to support its large population and maintain its complex infrastructure.

Excellent summaries of these collapse theories are provided by multiple sources, often citing the work of prominent archaeologists such as George Cowgill (who has considered invasion), Ross Hassig (economic decline), George Vaillant (internal revolt), and researchers like Mathew Lachniet and colleagues (drought).60

Rather than a single, isolated cause, Teotihuacan's collapse was likely a complex, systemic process where multiple stressors interacted and amplified one another, leading to what can be described as a cascade failure.

Imagine this: environmental pressures, such as a prolonged drought,60 would have severely strained agricultural production, leading to food shortages and potentially widespread famine. This, in turn, could have exacerbated existing social tensions and critically undermined the legitimacy of the ruling elite, who were traditionally responsible for mediating with the deities to ensure prosperity and cosmic order.60

Concurrently, economic decline, perhaps stemming from the over-exploitation of natural resources, the loss of control over vital trade networks, or the emergence of powerful competing centers in other regions, 60 would have further weakened the state's capacity to provide for its populace and maintain its authority.

These accumulating internal weaknesses, manifesting as social unrest, economic instability, and a loss of faith in the ruling institutions, would have made the city increasingly vulnerable to external pressures, such as attacks from rival polities or opportunistic invaders.2

The archaeological evidence of selective and deliberate burning of elite and ceremonial structures60 strongly points to a significant internal component in the city's destruction, possibly a violent uprising that was triggered or worsened by the convergence of these environmental, economic, and social problems.

This suggests a devastating cascade effect where these multifaceted challenges converged, ultimately leading to the dramatic downfall and abandonment of one of Mesoamerica's greatest ancient cities.

The analysis by Elizabeth P. Ale, for example, strongly supports this multi-causal perspective, arguing that drought could have led to famine, which, combined with deteriorating economic conditions, may have fueled an internal revolt.60

Unearthing More Secrets: Ongoing Research and Discoveries at Teotihuacan

Archaeological investigation at Teotihuacan is a continuous and dynamic process, with new discoveries regularly adding to and reshaping our understanding of this ancient metropolis. It's like a historical puzzle where new pieces are constantly being found! Research is spearheaded by Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), often in collaboration with national institutions like the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and various international universities and research teams, such as Arizona State University (ASU).8

Key areas of ongoing research and recent significant findings include:

-

Tunnels beneath Major Pyramids:

One of the most exciting avenues of recent research has been the exploration of tunnels found beneath Teotihuacan's major pyramids. A tunnel system was identified beneath the Pyramid of the Sun decades ago.27 More recently, a major tunnel discovered beneath the Temple of the Feathered Serpent by an INAH team led by Sergio Gómez has yielded an astonishing wealth of artifacts and information.[15 (citing FAMSF)] This tunnel, extending over 100 meters and ending in chambers, contained tens of thousands of offerings! Think finely carved greenstone sculptures, pyrite disks and spheres (possibly representing stars), rubber balls, vast quantities of marine shells, animal remains, botanical materials like seeds, and even traces of liquid mercury in shallow depressions, perhaps symbolizing sacred underworld lakes or mirrors to other realms. The tunnel's ceiling was found to be dusted with powdered pyrite and magnetite, which would have glittered in the torchlight, creating the effect of a star-filled subterranean cosmos. These discoveries offer unprecedented insights into Teotihuacano cosmology, ritual practices, and their symbolic recreation of the underworld.

Tunnel of Wonders: Subterranean Discoveries: Recent tunnel explorations beneath Teotihuacan's pyramids (especially the Feathered Serpent Pyramid) have yielded tens of thousands of offerings, including greenstone, pyrite 'stars,' and liquid mercury, revealing profound cosmological insights.

- Residential Compounds (Apartment Compounds): Excavations of Teotihuacan's unique apartment compounds continue to provide crucial data on the daily lives of its inhabitants, social organization, craft production activities, and the city's multiethnic composition.7 The Teotihuacan Mapping Project (TMP), initiated in the 1960s by René Millon, was a foundational effort that mapped the entire city and collected vast amounts of surface artifacts; its data and collections, now partly housed at the ASU Teotihuacan Research Laboratory, continue to be analyzed and yield new information.9 Projects like the Proyecto Arqueológico Tlajinga, Teotihuacan, focus on understanding urbanization and commoner life in specific districts.39

- Mural Paintings: The conservation and study of Teotihuacan's extensive mural paintings remain an important focus.15 New fragments are occasionally discovered, and advanced analytical techniques help in understanding the pigments, techniques, and iconography of this vibrant art form.

- Burials and Dedicatory Offerings: Ongoing excavations at the major pyramids, Sun, Moon, and Feathered Serpent, consistently reveal complex dedicatory burial caches associated with different construction phases.1 These findings continue to highlight the central role of ritual sacrifice (both human and animal), warfare symbolism, and state ideology in Teotihuacan's public ceremonies and monumental construction. Recent finds at the Moon Pyramid, for example, have revealed sacrifices with clear militaristic connotations and connections to foreign regions, including the Maya area.32

-

Understanding Governance, Collapse, and External Relations:

A major goal of current research is to shed more light on Teotihuacan's enigmatic political structure, the complex reasons for its eventual collapse, and the nature of its interactions with other contemporaneous Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Maya.4 The Plaza de las Columnas Complex Project, for instance, investigates palace compounds to better understand the city's political economy and administration.25 An INAH discovery in 2023 in Tlatelolco (within modern Mexico City) identified a Teotihuacan-era village dating to approximately 450-650 AD. The findings, including ceramics, architectural elements, and burials with Teotihuacan characteristics, suggest a more complex local economy than previously assumed, possibly involving specialized craft production, and expand our understanding of Teotihuacan's direct presence and influence even within areas that would later become central to the Aztec civilization.63

New Find! Teotihuacan in Future Aztec Lands: A 2023 INAH discovery in Tlatelolco (modern Mexico City) unearthed a Teotihuacan-era village (c. 450-650 AD), suggesting a more complex Teotihuacano presence and local economy than previously known, even in areas later central to the Aztecs.

Teotihuacan serves as a "living laboratory" for urban studies because of its immense scale, the fact that much of the ancient city isn't deeply buried under modern settlements (unlike Tenochtitlan), and the continuous application of new archaeological methods and scientific techniques.

The city's unique urban features, such as its rigid grid plan, distinctive apartment compounds, and the debated nature of its governance, offer alternative models of ancient urban life when compared to other civilizations in Mesoamerica and around the world.5

The remarkable discoveries within the subterranean tunnels28 provide direct, often unmediated, windows into Teotihuacano cosmology, ritual practices, and symbolic worldview, less filtered by later cultural interpretations.

Similarly, the ongoing analysis of residential compounds23 offers invaluable insights into the daily lives of commoners, the organization of craft specialization, and the dynamics of multiethnic cohabitation, aspects of ancient society that are often less visible in studies focused solely on monumental ceremonial centers.

The long and rich history of archaeological research at Teotihuacan, from the early 20th-century restorations8 to sophisticated modern scientific projects involving INAH, UNAM, ASU, and other institutions,8 means that there is a vast and ever-growing dataset that continues to be re-analyzed and expanded, leading to constantly evolving interpretations and new questions.

Ultimately, the study of Teotihuacan addresses themes of enduring relevance to modern societies, including the origins and declines of cities, the functioning of alternative systems of governance, and the ways in which religious beliefs and economic practices can change and interact over time.9

Tenochtitlan: The Eagle's Prophecy and the Aztec Capital

The Rise of Tenochtitlan: From Humble Beginnings to Imperial Power

The story of Tenochtitlan is one of a truly remarkable ascent, from very humble beginnings to becoming the magnificent capital of a vast empire, all within a relatively short span of Mesoamerican history.

Founded by the Mexica:

The people who founded Tenochtitlan, the Mexica (who later became the dominant group among the diverse peoples collectively known as Aztecs), were actually relative latecomers to the densely populated Valley of Mexico.1 According to their own traditions, they embarked on a long migration from a mythical ancestral homeland called Aztlán, located somewhere to the north or northwest of the Valley of Mexico, eventually arriving in the central highlands around the 13th century CE.1

-

Their legends tell us that their principal deity, Huitzilopochtli (meaning "Hummingbird on the Left" or "Southern Hummingbird"), guided them on their journey. He prophesied that they would find their destined home at a place where they witnessed a specific sign: an eagle perched upon a nopal cactus, devouring a serpent.67 This iconic image, now central to the Mexican national flag, was reportedly seen by the Mexica on a small, swampy island in Lake Texcoco.

The Eagle's Mandate: Tenochtitlan's Founding Myth: The Mexica were guided by their god Huitzilopochtli to found their city where they saw an eagle on a nopal cactus devouring a serpent, an iconic image now central to Mexico's national flag

- Tenochtitlan was officially founded on this island, with the traditional date given as March 13, 1325 CE.70 It's interesting to note that this specific date was actually chosen retrospectively in 1925 to commemorate the 600th anniversary of the city's founding.70 The city was built directly on and around the island within the brackish waters of Lake Texcoco.68

Rise as the Aztec Imperial Capital:

From these modest and challenging beginnings, Tenochtitlan rapidly grew in power and influence.

- A pivotal moment in its ascent was the year 1428 CE. Tenochtitlan, in alliance with the neighboring city-states of Texcoco and Tlacopan, formed the Triple Alliance.70 This powerful confederation successfully overthrew the then-dominant Tepanec kingdom of Azcapotzalco, which had previously held sway over the Mexica.1

- Following this victory, Tenochtitlan quickly emerged as the dominant partner within the Triple Alliance and became the undisputed political, economic, and religious heart of the rapidly expanding Aztec Empire.73 Under capable and ambitious emperors (Huey Tlatoanis) such as Itzcoatl, Moctezuma I (who came to power in 1440), and Ahuitzotl, the empire embarked on a series of military conquests, significantly expanding its territory and establishing a sophisticated system of tribute extraction from subjugated peoples.74

The Spanish Conquest:

The Aztec Empire, with Tenochtitlan as its glittering capital, was at its zenith when European explorers arrived.

- Hernán Cortés and his contingent of Spanish conquistadors landed on the Mesoamerican mainland and made their way inland, arriving at the gates of Tenochtitlan in November 1519.74

- What followed was a complex and brutal period of political maneuvering, alliances, and warfare. After being initially welcomed by the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II, relations soured, leading to Moctezuma's death and the expulsion of the Spanish from the city during the "Noche Triste" (Sad Night) in 1520. Cortés regrouped, gathering a large army of indigenous allies, most notably the Tlaxcalans, who were traditional enemies of the Aztecs. After a devastating siege that cut off supplies to the island city and was exacerbated by the outbreak of European diseases like smallpox (to which the indigenous population had no immunity), Tenochtitlan finally fell to the combined Spanish and indigenous forces on August 13, 1521.70 The magnificent city was largely razed to the ground, and upon its ruins, the Spanish began to build Mexico City, which would become the capital of the Viceroyalty of New Spain.71

Tenochtitlan's rapid transformation from a marginal settlement on a swampy island to the capital of a vast and powerful empire in less than two centuries is a testament to the Mexica's remarkable adaptability, strategic acumen, and military prowess.

The choice of an island location, while initially presenting significant environmental challenges,67 ultimately offered considerable defensive advantages against traditional Mesoamerican warfare tactics.72

More importantly, it spurred unique and ingenious urban developments, such as the chinampa agricultural system and the network of canals, which allowed the city to sustain a large population in an aquatic environment.67

The formation of the Triple Alliance in 142870 was a critical political and military turning point, enabling the Mexica and their allies to overthrow the existing regional hegemon and embark on their own path of imperial expansion.

The Mexica were renowned as skilled and fierce warriors, and military conquest was a central pillar of their imperial strategy, not only for territorial gain but also for acquiring tribute and the sacrificial victims demanded by their state religion.67

The city's burgeoning role as a major trading hub and the paramount religious center of the empire further solidified its power and prestige.73

This relatively swift trajectory to imperial dominance, fueled by a combination of strategic adaptation to their environment, astute political alliances, and relentless military expansion, stands in some contrast to the more gradual, centuries-long development of Teotihuacan into a major Mesoamerican power.

Tenochtitlan: An Urban Marvel on the Lake

Tenochtitlan was an absolute marvel of engineering and urban planning, a vibrant metropolis that seemed to float on the waters of Lake Texcoco.68 At its peak, it was one of the largest cities in the world, with population estimates ranging from over 200,000 to possibly 400,000 inhabitants, larger than contemporary European capitals like London or Paris!58

Island Setting and Hydraulic Engineering:

The city's foundation on a series of low-lying islands in the shallow, brackish western part of Lake Texcoco presented unique challenges and opportunities.68

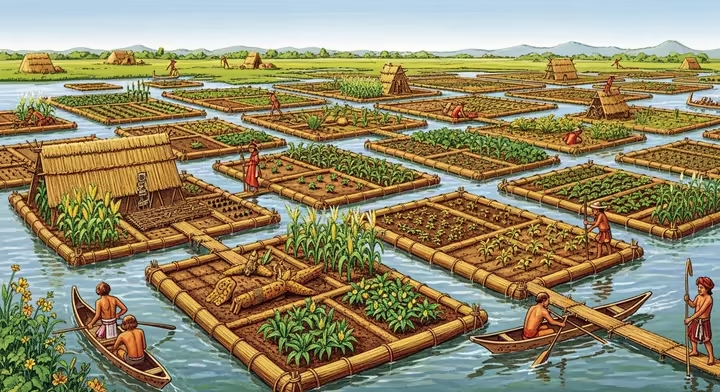

- The Mexica ingeniously expanded the habitable and arable land by constructing chinampas, artificial islands or "floating gardens", and gradually connecting them to form a larger urban landmass.67

- A sophisticated system of hydraulic works was essential for the city's survival and prosperity. This included building dikes, such as the impressive 16-kilometer (nearly 10-mile) long Nezahualcoyotl dike, which helped to control water levels, prevent flooding, and separate the saline waters of the eastern part of Lake Texcoco from the fresher waters surrounding Tenochtitlan.71 Aqueducts, most notably from the springs at Chapultepec, were built to bring fresh drinking water into the heart of the island city.68

Urban Design and Infrastructure:

Tenochtitlan was a highly organized and densely populated city, covering an estimated area of 8 to 13.5 square kilometers (3.1 to 5.2 square miles).70

- Causeways: Several wide, raised causeways, built of stone and earth, connected the island city to the mainland on the north, west, and south shores of the lake.67 These causeways were vital for transportation, communication, and military movement, and they often incorporated drawbridges for defensive purposes.

- Canals: An extensive network of canals crisscrossed the city, serving as the primary thoroughfares for movement and transport.67 Thousands of canoes plied these waterways daily, carrying goods, people, and tribute. Footpaths ran alongside many canals, creating a unique urban landscape.

-

Chinampas (Floating Gardens):

One of the most remarkable features of Tenochtitlan's urbanism was the chinampa system of agriculture.67 These were artificial rectangular plots of highly fertile land created by staking out sections of the shallow lakebed, fencing them with wattle, and then filling them with layers of mud, decaying vegetation, and lake sediment. Willow trees (ahuejotes) were often planted along their edges to help stabilize them.67 This intensive form of raised-field agriculture allowed for multiple harvests per year and was crucial for producing the vast amounts of food, maize, beans, squash, chili peppers, tomatoes, amaranth, and flowers, needed to support the city's large population.67 The chinampa system is still practiced today in areas like Xochimilco in Mexico City, a living testament to Aztec ingenuity.67

Engineering an Island City: Chinampas: Chinampas or 'floating gardens' were artificial agricultural plots built on the lakebed. These highly fertile islands allowed for multiple yearly harvests, feeding Tenochtitlan's massive population.

- Grid Layout and Neighborhoods: The city exhibited a relatively regular, grid-like layout, divided into four great quadrants or campans. These were further subdivided into numerous smaller districts or neighborhoods called calpullis.71 Each calpulli often had its own local temples, markets, and schools, fostering a sense of community identity within the larger urban framework.

The Sacred Precinct (Ceremonial Center):

At the very heart of Tenochtitlan lay the immense Sacred Precinct, a walled enclosure that served as the religious, ceremonial, and symbolic epicenter of the entire Aztec Empire.71 This area, roughly 380 by 330 yards, was surrounded by a "serpent wall" (coatepantli) and could hold thousands of people.76

-

Templo Mayor (Great Temple):

The most imposing and sacred structure within the precinct, and indeed the entire city, was the Templo Mayor.18 This was a massive twin-pyramid, approximately 60 meters (200 feet) high including its shrines, with dual staircases leading to two temples at its summit. The temple on the south side (often depicted as the right side when facing the temple) was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec patron god of sun and war, and was painted in red and white.77 The temple on the north side (left) was dedicated to Tlaloc, the ancient god of rain, water, and agricultural fertility, and was decorated in blue and white, symbolizing water and moisture.77 The Templo Mayor underwent at least seven major rebuilding and expansion phases, often coinciding with the coronation of new emperors, with each ruler seeking to outdo his predecessor in grandeur.78 The temple was seen as a symbolic representation of sacred mountains: Coatepec ("Serpent Mountain"), the mythical birthplace of Huitzilopochtli, and Tonacatepetl ("Mountain of Sustenance"), associated with Tlaloc and agricultural abundance.78

Heart of the Cosmos: The Templo Mayor: The Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlan's main temple, had twin shrines: one for Huitzilopochtli (sun, war, Mexica identity) and one for Tlaloc (rain, fertility), symbolizing the empire's core concerns and acting as a cosmic center.

- Other Structures within the Sacred Precinct: The precinct housed numerous other important religious and civic buildings. These included temples dedicated to other major deities such as Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca, a circular temple for Ehecatl (an aspect of Quetzalcoatl as wind god), a tzompantli (skull rack displaying the heads of sacrificial victims), a sacred ballcourt for the ritual Mesoamerican ballgame, priests' quarters, and the Calmecac, an elite school for training young noblemen for the priesthood and high government office.67

- Palaces: Adjacent to the Sacred Precinct were the sumptuous palaces of the emperor and the high nobility.68 The palace of Moctezuma II, as described by the Spanish conquistadors, was said to be vast, with hundreds of rooms, courtyards, beautiful gardens, aviaries, and even a zoo.68

- Markets: While the largest and most famous market in the region was located in Tenochtitlan's sister city of Tlatelolco (which eventually merged with and became subordinate to Tenochtitlan), Tenochtitlan itself also had designated market areas where a wide variety of goods were exchanged.58 The Tlatelolco market was described by the Spaniards as being immense, orderly, and visited by tens of thousands of people daily, offering goods from all corners of the empire and beyond.58

Tenochtitlan's urban form was a remarkable achievement, representing a profound symbiosis of sophisticated hydraulic engineering and deeply ingrained cosmological meaning. The city was a testament to the Mexica's ability to transform a challenging lacustrine environment into a thriving, sustainable metropolis, reflecting their worldview and their relationship with both the natural and supernatural realms.

The very act of constructing a major city on a series of islands in a lake, and then systematically expanding and provisioning it through the ingenious chinampa system, dikes, and causeways, demonstrates immense technical skill, collective effort, and ambitious vision.67 This was a city quite literally raised from the water, a human-made landscape in harmony with its aquatic surroundings.

At the city's sacred heart, the Templo Mayor stood not merely as a religious edifice but as a potent cosmic model, an axis mundi connecting the earthly realm with the celestial and underworld domains.

Its dual shrines dedicated to Huitzilopochtli (representing the sun, warfare, and Mexica imperial identity) and Tlaloc (representing rain, fertility, and the ancient agricultural foundations of Mesoamerican life) encapsulated the core concerns and dualities of the Aztec state and its ideology.77

The temple's specific orientation, its tiered structure, and the rituals performed there were all imbued with cosmological significance. The overall grid layout of the city and the organized division into neighborhoods71 suggest a meticulously planned urban space where social order and sacred geography were inextricably intertwined.

Even the legendary account of Tenochtitlan's founding, the divine prophecy of the eagle on the cactus67, provided a sacred mandate for the city's location, linking its physical existence directly to the will of the gods and its destiny as an imperial capital.

The city's innovative design simultaneously facilitated practical needs, such as intensive agriculture via the chinampas and efficient transportation via the canal network, and served imperial functions, including the collection and display of tribute and the performance of grand ceremonial displays of power.

This masterful integration of the practical and the sacred was a key element in Tenochtitlan's success, its unique identity, and its enduring legacy as one of the most extraordinary cities of the ancient world.

Life in Tenochtitlan: Aztec Society and Culture

Aztec society, with Tenochtitlan at its very peak, was a complex and highly structured civilization, characterized by clear social layers, a rich cultural heritage, and sophisticated institutions.

Social Organization: Who Was Who?

The social structure of the Aztec Empire was distinctly hierarchical, with well-defined classes and roles for everyone.

- Pipiltin (The Nobility): At the very top of the social pyramid were the pipiltin, the hereditary nobility.67 They made up a small percentage of the population (around 5%) but held significant power and privileges.83 These perks included the right to own land (often in the form of large estates), to wear luxurious garments and jewelry made of precious materials like jade and gold, to consume elite goods, and to command labor from commoners.83 The pipiltin filled the highest positions in the government, the military, and the priesthood. The most powerful among them were known as lords (teuctin).

- Macehualtin (The Commoners): The vast majority of the Aztec population belonged to the macehualtin class, the commoners.83 Originally, this group consisted primarily of farmers, but as Aztec society grew more complex, it came to include a wide range of artisans, craftspeople, local traders, and laborers.83 Most macehualtin were organized into calpollis (singular: calpulli), which were kin-based social units that also functioned as landholding corporations, providing their members with access to agricultural land and a sense of community identity.83 While commoners had fewer privileges than nobles, they could achieve a degree of social mobility, primarily by demonstrating exceptional bravery and success in warfare, such as by capturing enemies for sacrifice.83

- Pochteca (The Merchants): A distinct and influential group within Aztec society were the pochteca, specialized long-distance merchants.58 They organized and led trading expeditions to faraway regions, often dealing in luxury goods such as tropical bird feathers, jade, cacao, and exotic animal skins. The pochteca had their own guilds, deities, and social standing, and they sometimes served the empire as emissaries, information gatherers, or even spies in foreign territories.58

- Slaves (Tlacotin): Slavery did exist in Aztec society, but it was quite different from the chattel slavery practiced in many other parts of the world.83 Individuals could become slaves (tlacotin) primarily due to debt, poverty (selling oneself or one's children into servitude), or as a punishment for certain crimes. However, slavery wasn't typically a hereditary status; the children of slaves were born free. Slaves also had certain rights and could potentially gain their freedom.83

Language and Writing:

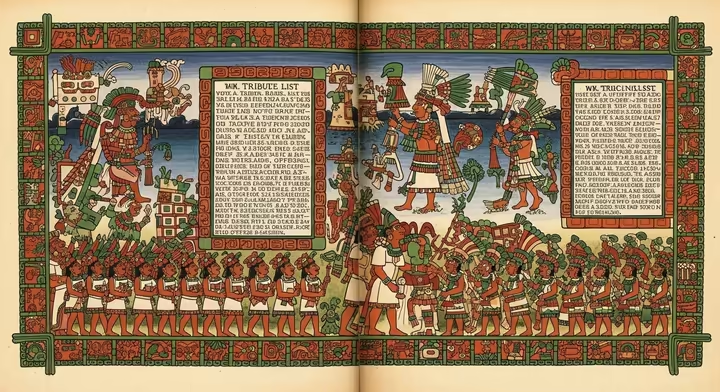

The dominant language spoken throughout the Aztec Empire, and the common tongue of much of central Mexico at the time, was Nahuatl.4 Nahuatl is a Uto-Aztecan language still spoken by over a million people in Mexico today. The Aztecs used a pictographic and ideographic writing system. This system combined images (pictures representing objects or concepts) with glyphs representing sounds or ideas.[15 (citing FAMSF for Teotihuacan, implying Aztecs also had one for Teotihuacan context)] This was used to record historical events, genealogies, tribute lists, religious calendars, and mythological narratives in screenfold books made of bark paper or deerskin, known as codices.

Daily Life:

Daily life in Tenochtitlan and the Aztec Empire varied greatly depending on social class and occupation.

-

Education:

The Aztecs placed a strong emphasis on education, with formal schooling available for children from different social strata.67 Noble children, particularly boys, attended the Calmecac, an elite institution where they received rigorous training for careers in the priesthood, high government administration, or military leadership. The curriculum included subjects such as religion, history, law, calendrics, astronomy, rhetoric, poetry, and military strategy.67 Commoner children, primarily boys, attended the Telpochcalli ("house of youth"), where they received practical instruction in warfare, crafts, and civic duties.67 Girls also received education, often focused on domestic skills, religious duties, and crafts like weaving and featherworking, with some attending priestess training schools.67

Aztec Education: Forging Society's Pillars: Aztecs valued education. Nobles attended the Calmecac for elite training (priesthood, government). Commoners attended the Telpochcalli for practical instruction in warfare, crafts, and civic duties.

- Agriculture and Diet: The Aztec diet was based on staple crops such as maize (corn), beans, squash, chili peppers, tomatoes, and amaranth, many of which were intensively cultivated on the fertile chinampas surrounding Tenochtitlan.1 Tortillas made from maize were a dietary cornerstone, often eaten with sauces made from chilies and tomatoes, and accompanied by beans.67 Luxury foods for the elite included cacao (consumed as a beverage), meat from hunted game (deer, waterfowl) or domesticated animals like turkeys and hairless dogs (itzcuintli), and fish brought fresh from the Gulf Coast by swift runners.67

- Crafts and Arts: Aztec artisans were highly skilled in a variety of crafts, producing exquisite works in pottery, stone sculpture (often using volcanic rock), featherwork (creating intricate mosaics for shields, headdresses, and garments), gold and silver smithing, and lapidary arts (working with jade, turquoise, and obsidian).67

While Aztec society was clearly stratified with a powerful hereditary nobility, it wasn't entirely rigid. Avenues for social mobility did exist, most notably through demonstrated prowess in warfare and through dedication to the priesthood.

This provided an important incentive structure that supported and reinforced the key institutions of the Aztec empire. Commoners (macehualtin) who distinguished themselves in battle by capturing enemies for sacrifice could earn promotions in rank, acquire privileges, and gain prestige, potentially even rising to positions of local leadership.83

This system directly fueled the military expansion of the empire and ensured a steady supply of sacrificial victims, which were central to the state religion and its cosmological underpinnings.

Similarly, the Calmecac, the elite schools, prepared noble sons for high-ranking and influential positions within the priesthood or state administration.67

The priesthood itself was a powerful and respected institution, responsible for managing the complex religious life of the empire, overseeing education, interpreting calendars and omens, and often holding advisory roles in government.75

This system of advancement through military or religious service ensured a continuous supply of dedicated personnel for these crucial imperial functions.

It also offered a pathway for ambitious and capable individuals to improve their social standing, thereby channeling their energies in ways that generally benefited and strengthened the Aztec state.

The Spiritual World of the Aztecs: Beliefs and Practices

Religion was a pervasive and integral force in Aztec life, shaping their worldview, social customs, political actions, and artistic expressions. Theirs was a complex polytheistic system, with a vast pantheon of gods and goddesses, many of whom were inherited or adapted from earlier Mesoamerican civilizations, including those revered at Teotihuacan.10

The Aztec Pantheon: A Host of Deities

Among the most significant deities in the Aztec pantheon were:

- Huitzilopochtli: The supreme patron god of the Mexica people, Huitzilopochtli was the god of the sun, warfare, and tribal destiny.[83 (implied for Mexica), 10] His temple was one of the two principal shrines atop the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan, and he was believed to require constant nourishment in the form of human hearts and blood to continue his daily journey across the sky.

- Tlaloc: The ancient Mesoamerican god of rain, storms, water, and agricultural fertility, Tlaloc was of paramount importance to an agricultural society.10 He shared the summit of the Templo Mayor with Huitzilopochtli, signifying the critical balance between warfare/tribute (Huitzilopochtli) and agricultural sustenance (Tlaloc) for the empire. His worship had deep roots in Mesoamerica, with clear antecedents at Teotihuacan.

- Quetzalcoatl: The "Feathered Serpent," Quetzalcoatl was another major deity with ancient origins, prominently represented at Teotihuacan.10 In the Aztec pantheon, he was associated with wind (as Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl), the planet Venus (the morning star), creation, wisdom, learning, arts, crafts, and was the patron god of the priesthood. He played a key role in Aztec creation myths.

- Tezcatlipoca: The "Smoking Mirror," Tezcatlipoca was a powerful and often capricious deity associated with the night sky, darkness, magic, prophecy, fate, and rulership.10 He was often depicted as a rival or counterpart to Quetzalcoatl in creation myths.

- Other important deities included Xipe Totec ("Our Lord the Flayed One"), god of spring, agricultural renewal, and goldsmiths; Coatlicue ("She of the Serpent Skirt") or Tlaltecuhtli (Earth Lord/Lady), a primordial earth deity; Chalchiuhtlicue ("She of the Jade Skirt"), goddess of freshwater lakes, rivers, and streams, and consort of Tlaloc; and Mictlantecuhtli and Mictlancihuatl, the lord and lady of Mictlan, the underworld.18

Rituals and Ceremonies:

Aztec religious life was characterized by a rich and complex cycle of rituals and ceremonies, meticulously timed according to their sophisticated calendrical systems.83 The Aztecs used two main calendars simultaneously: the Xiuhpohualli, a 365-day solar calendar divided into 18 months of 20 days plus 5 "unlucky" or "empty" days at the end; and the Tonalpohualli, a 260-day sacred ritual calendar, composed of 20 day-signs combined with numbers from 1 to 13. The alignment of these two calendars every 52 years marked a major cycle, celebrated with the New Fire Ceremony (Xiuhmolpilli), a time of renewal and cosmic re-dedication.71

-

Human Sacrifice:

This was one of the most prominent and widely discussed aspects of Aztec religious practice.10 The Aztecs believed that the gods, particularly Huitzilopochtli as the sun, required nourishment in the form of human hearts and blood to maintain their strength, ensure the continuity of the cosmos, and prevent the world from descending into darkness and chaos.10 Victims for sacrifice were often prisoners of war, which provided a strong religious impetus for continuous warfare. While the scale of human sacrifice is debated, with some early Spanish colonial accounts likely containing exaggerations for political purposes,86 archaeological evidence from sites like the Templo Mayor confirms its practice.

Lifeblood of the Gods: The Role of Human Sacrifice: Aztecs believed gods, especially the sun god Huitzilopochtli, needed human hearts and blood for nourishment to maintain cosmic order. War captives were common sacrificial victims, linking religion directly to military expansion.

- Offerings: In addition to human sacrifice, the Aztecs made a wide variety of offerings to their gods. These included animal sacrifices (such as eagles, jaguars, and deer), as well as offerings of food, maize, pulque (an alcoholic beverage made from agave sap), precious materials like jade, turquoise, gold, obsidian, and elaborate featherwork.79 Many such offerings have been discovered in caches at the Templo Mayor.

- Festivals: Numerous festivals, dedicated to specific deities and often tied to the agricultural cycle or important mythical events, were held throughout the year.77 These festivals involved processions, music, dancing, feasting, and various ritual performances, often culminating in sacrifices. The festival of Panquetzaliztli, for example, celebrated Huitzilopochtli's birth and triumph over his sister Coyolxauhqui and his 400 brothers, a myth reenacted at the Templo Mayor.77

Aztec religion, particularly the central cult of their patron god Huitzilopochtli and the associated practice of large-scale human sacrifice, was inextricably linked to their military endeavors and the expansion of their empire. This created a powerful, self-reinforcing ideological and political cycle.

The core belief that Huitzilopochtli, as the sun god, required a constant supply of human blood and hearts to sustain his cosmic journey and thereby preserve the world provided a potent religious justification for continuous warfare.10

Warfare, in turn, was the primary means by which the Aztecs obtained the necessary sacrificial victims, who were typically prisoners captured from enemy states.67 This created a perpetual need for military campaigns and expansionist policies.

Successful military ventures not only provided these essential victims but also led to territorial expansion and the acquisition of vast amounts of tribute from conquered peoples.67

This tribute, in the form of goods and labor, further enriched Tenochtitlan, supported the state apparatus, and funded the elaborate religious institutions and ceremonies.

The highly public and dramatic performance of sacrifices, especially at the Templo Mayor in the heart of the capital, served as a powerful and intimidating display of imperial power and religious authority.81 It reinforced Aztec dominance over both their subjects and their enemies.

This intricate system thus created a feedback loop: religious ideology fueled and legitimized warfare; warfare provided sacrificial victims and economic tribute; and the public ritual display of sacrifice reinforced the ideology, the power of the gods, and the authority of the Aztec state.

This complex interplay between religion, warfare, and imperial expansion was a key driver of the Aztec Empire's growth and consolidation. But it also likely sowed seeds of resentment and fear among subjugated populations, which would later be exploited by the Spanish conquistadors.

Tenochtitlan: The Political and Economic Heart of an Empire

Tenochtitlan wasn't just a large city; it was the undisputed political, administrative, and economic heart of the formidable Aztec Empire, a center from which power radiated outwards and to which wealth flowed inwards.68

Center of the Empire:

- Government: The Aztec Empire was ruled by an emperor, known as the Huey Tlatoani ("Great Speaker"). He was considered to be divinely appointed and held the ultimate political, military, and religious authority.75 The position wasn't strictly hereditary by primogeniture; upon an emperor's death, his successor was typically chosen by a council of high-ranking nobles, usually from among the deceased ruler's close relatives (like a son or brother) deemed most capable.75 The Huey Tlatoani was assisted in governance by a complex bureaucracy that included a council of four principal advisors (who were often potential successors), and a second-in-command known as the Cihuacoatl ("Woman Serpent," though the office was held by a man), who managed the day-to-day administration of the capital and the empire.75

- Tribute System: A cornerstone of the Aztec imperial economy was the extensive tribute system imposed on conquered city-states and provinces.67 Subjugated peoples were required to pay regular tribute to Tenochtitlan in the form of a vast array of goods. This included foodstuffs (maize, beans, etc.), raw materials (cotton, timber), manufactured items (textiles, pottery, warrior costumes), luxury goods (jade, turquoise, gold, exotic feathers, cacao beans), and sometimes labor or military service. This constant influx of tribute supported the population of Tenochtitlan, financed the state and its military, and enriched the nobility and priesthood.

- Trade: Tenochtitlan, and particularly its sister-city Tlatelolco with its massive marketplace, served as a major hub for trade and commerce, facilitating the exchange of goods from all corners of Mesoamerica and beyond.58 Specialized merchants, the pochteca, played a crucial role in this long-distance trade.

- Law: The Aztecs possessed a relatively sophisticated legal code that addressed various offenses, including theft, murder, drunkenness, and property damage.75 A system of courts and judges administered these laws, with possibilities for appeal to higher courts. Punishments could be severe, often including death, enslavement, or public humiliation.75

The Aztec Empire maintained control over its extensive and diverse territories primarily through a system of tribute extraction and a form of indirect rule, rather than by imposing direct political administration or complete cultural assimilation in all conquered regions. This imperial strategy had both inherent strengths and significant weaknesses.

The Huey Tlatoani and the central administration in Tenochtitlan generally didn't interfere deeply with the internal governance of conquered city-states, allowing local rulers and existing power structures to remain in place as long as the stipulated tribute was paid regularly and loyalty to the empire was maintained.75

This approach allowed for a degree of local autonomy, which could potentially reduce the administrative burden on the imperial capital and facilitate a more rapid expansion of the empire, as existing local elites could often be co-opted or coerced into serving Aztec interests.